On a night in Paris in 1914, Gertrude Stein was walking with Picasso when the first camouflaged trucks passed by. ‘We had heard of camouflage,’ Stein recalled, ‘but we had not seen it, and Picasso, amazed, looked at it and then cried out, yes it is we who made it, that is Cubism.’

The art of blending into the background was indeed discovered by painters, but the roots of camouflage, Mary Horlock argues, lay in Impressionism. French camouflage manuals cited Corot rather than Picasso: ‘It is by variations of light and shadow, often very delicate, that one recognises how an object is solid and detached from its background.’

For Solomon J. Solomon, the Royal Academician who built observation posts disguised as trees in the first world war, camouflage was a form of realism. In a letter to the Times in 1915, he argued that only an artist skilled at modelling could understand the workings of camouflage, and similarly only a writer skilled at looking can understand why a man might also make himself disappear.

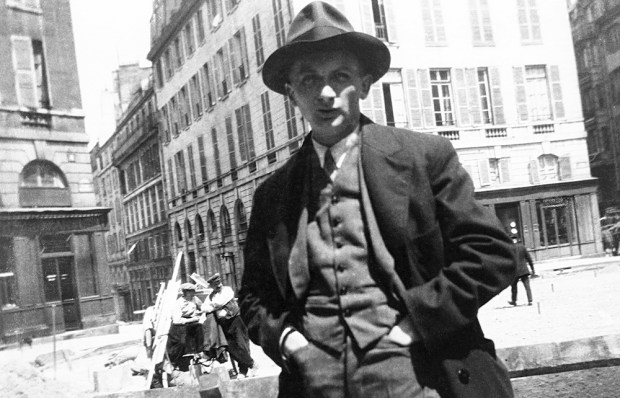

Horlock is a novelist and former curator at Tate Britain, and her moving and unusual book weaves together the story of camouflage with the story of the search for her great grandfather, Joseph Gray, one of the band of camoufleurs who studied the techniques of Solomon and thus changed the landscape of the second world war. ‘How do I get close to a man who was so good at hiding,’ Horlock asks; ‘a man who had made camouflage the fabric of his life?’

Born in South Shields in 1890, Gray wasn’t always invisible. While Solomon was experimenting with camouflage in his garden at St Albans by dyeing butter muslin and hanging it on tennis nets, Gray was in the trenches with the 4th Black Watch Regiment, where he fought in the battles of Neuve Chapelle, Festubert and Loos. An expert observer — he studied painting at the South Shields school of art — he also made sketches of enemy positions. When he was wounded by sniper fire in 1916, he became war artist for the illustrated weekly, the Graphic, where his trench sketches were turned into published illustrations. Gray’s art for the Graphic, says Horlock, ‘had an immediacy and a naivety which spoke of direct experience’.

In 1918 he was commissioned by the newly created Imperial War Museum to paint large oil canvases based on his direct experience. The first of these, ‘A Ration Party of the 4th Black Watch at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, 1915’, showed the wild dash for cover of the soldiers who left the trenches to deliver rations to the company. In the interests of accuracy, Gray used the men themselves as models (he used photographs of those who were killed), and the result is an image of ‘ragged spectres’, as Horlick puts it, ‘half sunk in mud, half lost in shadow’. Gray presented the battalion ‘in a kind of limbo’, caught ‘between light and dark, between life and death’. ‘A Ration Party’ is an unnerving painting, not least because Gray’s painstaking devotion to realism created an effect of supernatural unreality. Since he was also there, Gray included himself in the canvas — but only just. Joseph Gray, as Horlock notes, is ‘the most obscure figure in the corner, a face hooded and hidden in the shadows, almost invisible’. He was already concealing himself.

The same uncanny realism was evident in Gray’s second commissioned canvas, ‘After Neuve Chapelle’. In a representation of post-battle dreariness, he included the face and figure of every man who fought that day. Joseph Gray was the thing itself: a nuts-and-bolts artist in the age of modernism, and ‘After Neuve Chapelle’ was greeted with acclaim. It was then swiftly forgotten.

Five months after returning from No Man’s Land, Gray had married a stenographer called Agnes Dye and they settled in Dundee, where their daughter Maureen — Horlock’s grandmother — was born. Throughout the 1920s he worked on etchings and dry points which sold sufficiently to keep the family afloat. But in 1931 they moved to London where, renting the Tite Street rooms formerly occupied by John Singer Sargent, Gray failed to establish himself as a portrait painter and instead wrote a treatise on Camouflage and Air Defence.

Realising that the author had a genius for visual deception (‘there are no actual lines in nature,’ Gray explained, ‘only tones’), the War Office appointed him as a camouflage officer. The manuscript of Camouflage and Air Defence, which to Gray’s disappointment was never published, can be found today in a sealed box in the Imperial War Museum.

It is from another document squirreled away in the Imperial War Museum, the ‘ABC of Camouflage’, that Horlock realised the ingenious structure her book should take. Written by a Major D.A.J. Pavitt as an instructional tool to make troops ‘camouflage minded’, the ‘ABC of Camouflage’ is a jaunty verse which begins, ‘A stands for Aeroplane: his is the eye/ That Camouflage tries to defeat; this is why’. Using as chapter headings each of Major Pavitt’s 26 lines, Horlick tells Gray’s story as an ABC.

The next challenge Gray set himself was to discover a material that was light, portable and porous enough for constructional camouflage purposes. His notebooks of this time (also stored in the Imperial War Museum) are filled with questions such as ‘How to get away from representation. How?’ and ‘One conveys the idea of the true by means of the false’, a line he lifted from Degas. It was the Impressionists who came to his rescue. Degas and Corot ‘responded to natural light’, says Horlock, and built up texture by ‘daubing and dashing their paint. It was easy to recognise features in an Impressionist landscape and yet it looked almost abstract close up’.

The perfect material for creating an impression of a landscape, Gray realised, was steel wool, otherwise used for scouring pots. When the tough fibres were knitted together, painted green and laid out like a carpet, they ‘bristled and buckled like something alive’. Close up, the wiry cover appeared abstract, but from a distance it looked just like grass. Steel wool could also be made to look like hills, hedgerows and hayricks, and masses and masses of it could even make a castle invisible. The first use of steel wool as camouflage was in Cobham in 1941. ‘The quarry vanished,’ reported a witness, ‘and in its place appeared undulating grass slopes with bushes and saplings here and there.’ Even at the closest range it was impossible to see where wire ended and nature began.

So Joseph Gray turned from a first world war artist who represented reality to a second world war artist who disguised reality. And at the same time that he was experimenting with artificial landscapes, he began to vanish from the surfaces of his own domestic world.

Mary Meade, whom he met in 1938, was 15 years younger than Gray. ‘I can’t camouflage what I feel,’ he wrote to her in one of the many love letters reproduced in these pages, ‘and I won’t try to’. Mary worked for a magazine called the Needlewoman, where Gray secured a job for his daughter. Maureen had no idea that her father and Miss Meade were lovers, although she was aware that her parents’ marriage had broken down. During the next five years, Gray disappeared from the life of his wife and child and immersed himself in the more bohemian world of Mary and the Meade family.

Gray had a good war. Better than good: he had a fantastic war. ‘I say,’ he wrote to Mary, ‘what a war! Fantastic — what marvellous subjects for drawing.’ ‘The barrage over London made a fantastic sight’, he said of the Blitz. Typically, he liked the blackouts best, when ‘I lead a fantastic life’. It was when the lights came back on that life became difficult. He married Mary Meade in 1943, and saw no more of Agnes or Maureen. When he died in 1963, his grandchildren assumed he had been dead for years. The fame he deserved as a war artist, a writer and a camoufleur eluded him. ‘Art?’ he later said, ‘What has art ever done for us as a family?’ Thanks to this subtle and intelligent book, Gray should now be more visible.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in