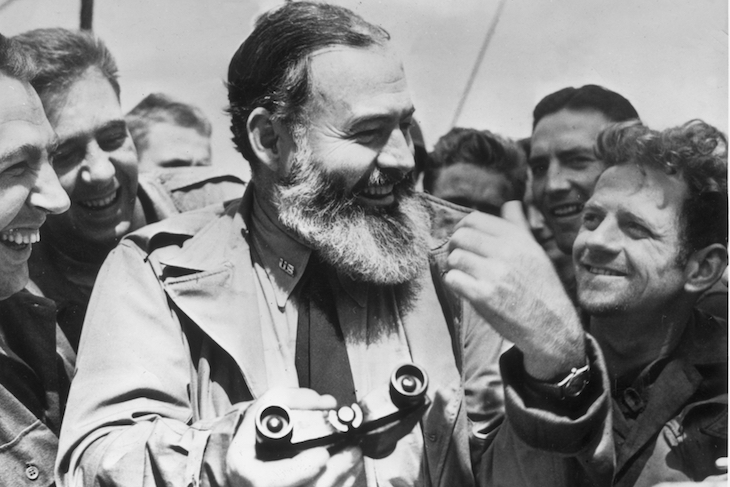

In Havana, one week before President Obama unthawed half a century of cold relations with Cuba, I talked to the last fisherman to have known Ernest Hemingway. Oswald Carnero came from Cojimar — where the writer kept his boat, the Pilar — and was one of the villagers to whom Hemingway dedicated his Nobel Prize after publishing The Old Man and the Sea. Carnero had met him in 1950, aged 13. ‘He was bringing in a big marlin on his boat. He asked me if I could skin the fish.’

Thereafter Carnero sold Hemingway turtle flesh for soup and ran errands, scurrying back to the Pilar with bottles of White Horse, and going up to his house, the Finca Vigía. (‘Put your feet in the water,’ Hemingway told him, motioning at the pool, ‘Ava Gardener has just swum naked here.’)

Hemingway pumped Carnero for details of the Gulf Stream to incorporate in the film of The Old Man and the Sea, about an ageing Cuban fisherman who hooks a giant marlin. ‘I was in the movie. I had to row out in a boat and fish.’ Now aged 79, Carnero was banned even from stepping into a boat without a licence, in case he sailed 90 miles north to Miami — which, from the expression in his landlocked eyes, he felt a powerful tug to do.

Will Millard is a BBC documentary maker from the Fens who, like Carnero, has fished all his life. He takes the central drama behind Hemingway’s last novel as the motivation to continue the story from where Papa left off, but from the perspective of an English fresh-water angler. His giant marlin is a small sand-eel in Dorset which he hooks and then loses. In the competitive world of sand-eels, this little lost fish — ‘knocking on the door of one pound’ — was ‘an absolute monster’, and would instantly have gained for Millard a new British fishing record. ‘There are few sensations in life that can match the angler’s immeasurable sense of loss when a big fish slips from their grasp.’

His failure inspires him to go out and find ‘the native, truly wild populations’ of our island’s fish — e.g. perch, carp, pike, eel — and sets Millard on a redemptive towpath that sees him discovering the hidden waterways of Britain. By selecting the most unlikely and, at first glance, most unpropitious beats, he picks up material for a book as delightful and informative as Morten Strøksnes’s Shark Drunk, which tracked that Norwegian journalist’s attempt to catch a Greenland shark. The Old Man and The Sand Eel will be enjoyed by anyone who loves the challenge and mystery of baiting a hook and plopping it into the water, then waiting with every atom of your concentration to feel a responsive handshake from the deep. ‘Fishing by its very nature is prying into a largely unseen world and trying to make a connection.’

Millard is a cheerful version of Cormac McCarthy’s solitary adolescent hero Suttree. His quest takes him to ‘spots where most wouldn’t think to cast a line: tangled underworlds, crumbling docks and urban rivers, the dwellings of the truly abandoned’. Here, in the hardest places to catch them, among submerged tyres and supermarket trolleys, live the best fish. Behind a Watford Gap service station, an 8lb eel. On the Grand Union Canal near Leicester, a record-breaking tench. From a Cardiff canal, Millard draws a spawn-filled female pike like ‘a precious sword from the stone’. His Arthurian moment is reverently observed from under the bridge by a spliff-smoking boy: ‘I’ve seen some crazy shit down here but I ain’t never seen anything like that.’

No split-cane toff, Millard has little truck with the snobbery he sees exemplified by dainty rodmen like Jeremy Paxman for whom fly-fishing embodies ‘some Platonic ideal’ — when all you’re trying to do is ‘convince a fish that a piece of fluff is worth having’. He writes: ‘If I were allowed to fish using only one method for the rest of my life then the float would be it.’ About his piece of fluff, he’s not choosy, once spending an afternoon fishing with a Pot Noodle. He recommends chicken offal for eels, maggots for roach, roaches’ eyeballs for perch — although drawing the line at live ducklings for pike, as favoured by one Welsh fisherman he encountered. In the end, the bait matters less than the attitude of the baiter. A fellow fishing author reminds him: ‘The only unsuccessful fisherman is the one who is not enjoying what he’s doing.’

As with all good fishing books, Millard’s quest ‘to find Britain’s lost waterways’ becomes an excuse to trawl back over his life. The local doctor’s son, he grew up near Ely (named after the eel), ‘where people go mad because of the lack of hills’.

He found his sanity, aged five, in float-fishing for roach. His own Papa Hemingway was his grandfather, ‘the greatest of all the great eels in my life’, an engineer on the Thames Barrier who had fished during the Blitz and who taught him the three secrets of angling: ‘Repetition and consistency’, plus ‘any good grandparent’. Their relationship is beautifully drawn, so that Millard’s prose can seem at times trapped in the formaldehyde of adolescence, and perhaps not fearful (enough) of hyperbole — the death’s head moth is ‘the coolest insect that ever lived’; a small shrew sniffing the air is ‘my most exciting discovery of all time’.

But his exuberant lightness is deceptive, too. Taught by a master, he knows his stuff. He learns to blend in with his surrounds until, whiskers aquiver, he becomes a part of them, sensible to the shortening days, alert to the sounds of animals emerging from their burrows at night — or, tragically, no longer emerging. The pool frog, the orache moth, the slimy burbot, the water vole — his book is also a passionate quest for what he discovers we are about to lose: one in ten of the UK’s wildlife species is threatened with extinction. One in five of our birds is now on the protected list, but the statistics are direr for fish. By 2010 the Environment Agency had recorded a catastrophic 95 per cent decline in the eel population.

Millard brings his discoveries and wisdom, like a catch, back from the towpath. It makes him notice and enjoy life around him, and return to the water refreshed. In his water-based religion, each cast is a secret prayer. Sometimes the exciting pressure at the other end is a sodden suit jacket; sometimes, it’s another huge monster that gets away; sometimes it’s a large carp that he ‘flukes out’ with no waiting or effort; and sometimes there’s no pressure — teaching Millard that it actually doesn’t matter if you don’t catch anything at all, and that losing is ‘an acceptable part of what it means to be a true fisherman, and a better person’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in