Apparently it’s called ‘expectation management’. Pollux, Esa-Pekka Salonen’s new work for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, takes its name from Greek myth. But as Salonen explains in his programme note, there’s more: lots more. It’s intended to form a diptych with a second piece called (naturally enough) Castor. It’s also part-inspired by Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, and an image (Salonen compares it to Salvador Dali) of a tree growing out of an ear. And finally there’s a ‘mantra rhythm’, which Salonen heard played by a post-grunge band ‘during dinner in a restaurant in the 11th arrondissement of Paris’, which all sounds very civilised.

Still, that’s a lot of concepts for a ten-minute piece, and I’m ashamed to admit that having read the programme and made notes throughout the performance, I can’t actually remember what much of it sounded like. ‘Ikea Hollywood’, I’ve scribbled. I recall spaciousness and transparency: dark curves of sound caught in the sunset glow of the lustrous LA string section. There were spangles of glockenspiel, and near the end, some lounge piano noodling against satin violins.

As for the rest: sorry, gone, scorched from the memory by a performance of Edgard Varèse’s Amériques in which Gustavo Dudamel drenched this explosive urban soundscape in impressionist half-tints, made mechanical sirens wail as plaintively as wounded animals and carried the music forward with a sense of rhythmic purpose that made The Rite of Spring sound like Einaudi. Smudges of low string tone; juicy bursts of telephone bells — Dudamel inflected passing details with a dance-like swing, generating a giddy momentum and a series of climaxes whose raw power practically stripped the lining from your ears. It was beautiful: one of those performances that change the way you think about a composer. And to be honest, whatever I’d expected from Dudamel and the LA Philharmonic’s three-day Barbican residency, it wasn’t that.

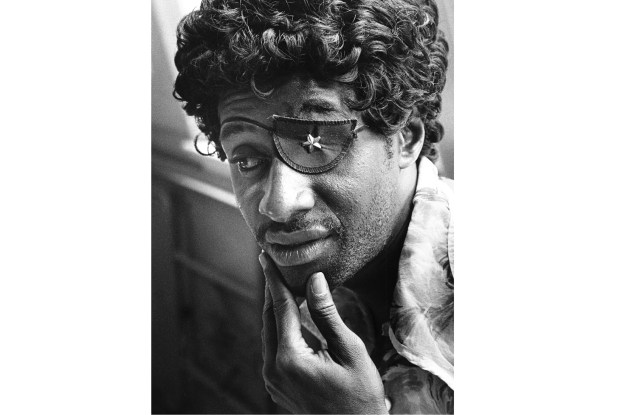

Because no question, Dudamel needs some expectation management too. To put it extremely crudely, current opinion is polarised between those who continue to see him as a sort of artistic Messiah (the classical-music business is never happier than when proclaiming the ‘life-changing’ powers of its core product) and a sizeable faction who prefer their conductors dead (or as close as possible), and who object both to Dudamel’s hairstyle (always a popular line of attack when a critic has nothing to say about the music — see also Sir Simon Rattle) and to what they see as his problematic past relationship with the rotten government of his native Venezuela.

That lot, in particular, will have been sent tutting back to their Karajan box sets (no political issues there) by Dudamel’s account of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the closing work of the residency. From the opening chord — horns asserting themselves against motoring second violins — to the headlong brilliance of the final flourish, this was a performance in the Toscanini tradition, with bold colours, crisp articulation and heart-on-sleeve immediacy. If there were casualties along the way (nothing in the Adagio sounded truly quiet — that had to wait for the first appearance of the ‘Joy’ theme), there was an undeniable thrill in hearing Beethoven handled with such rhythmic verve, and witnessing this massive virtuoso orchestra being hurled around corners with the speed and agility of a period-instrument band.

The previous night, Dudamel directed a contemporary programme whose first two items, Frederic Rzewski’s Attica and Julius Eastman’s Evil Nigger, proved again that a fascinating concept doesn’t necessarily translate into a convincing musical experience. Even with majestic narration from Soloman Howard, the limp sub-Copland meandering of Attica (inspired by a 1970s prison riot) sounded like a GCSE classroom composition project. Ted Hearne’s Law of Mosaics for string orchestra had more muscle: it was fun to hear solo violins and cellos spraying squiggly microtonal graffiti, and to spot the quotes in Hearne’s third movement, whose title, ‘Climactic moments from Barber’s Adagio for strings and Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, slowed down and layered on top of one another’, probably gets the expectation game about right.

Dudamel conducted each of the modern works with a clear, meticulous beat and intense concentration. His first action at the end of the Varèse was to thank his principal players; and having introduced the Eastman (which, being for four pianos, didn’t need a conductor) he sat in the audience and listened. This was not the behaviour of a superstar ego, and the choice of modern repertoire provided a context in which Dudamel’s high-res approach to the classics made perfect sense. In 2018 there’s no reason why Beethoven seen through the lens of John Adams’s Harmonielehre should be any less meaningful than Beethoven filtered through Götterdämmerung. Stuff the hype, and the still more toxic anti-hype. Dudamel’s seriousness of purpose seems to me to be self-evident, and I don’t understand why more commentators aren’t saying so. Perhaps they aren’t listening.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in