What is the Royal Academy? This question set me thinking as I wandered through the crowds that celebrated the opening of the RA’s new, greatly extended building. After all, there is nothing else quite like this institution anywhere else in the world.

It was a terrific party: a mêlée of artists, journalists, politicians and media types such as I have not seen since the inauguration of Tate Modern 18 years ago (with the unexpected addition of DJs and high-volume music). The whole gang was there, and rightly so. This is a significant addition to the amenities of London, including, among other things, two new suites of galleries at 6 Burlington Gardens, behind Burlington House. Amid the throng in the galleries where Tacita Dean’s exhibition Landscape currently hangs, I happened to bump into Nicholas Serota. As terse as ever, he delivered a two-word verdict that went straight to the point: ‘good spaces.’ Which is what counts most to us, the public.

The flamboyant classical-cum-baroque building at 6 Burlington Gardens was designed by Sir James Pennethorne in the 1860s for the University of London (and later had various occupants, including the old Museum of Mankind). More recently, the RA has held a number of exhibitions here, but there was always something a bit makeshift about the galleries. The art never seemed quite at home.

It does now. The architectural joining and opening out have been deftly handled by David Chipperfield, and in some cases the interiors have been returned to their original condition by Julian Harrap — the reinstated 19th-century lecture theatre, for example. The RA has gone from having no auditorium for talks to having the best of any museum in London. Except, of course, that it is not exactly a museum.

Again the question arises: actually, what is the RA? And the answer is an ad hoc amalgam of professional association, private club, exhibition venue and art school. There are institutions elsewhere that carry out some of those functions — the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid for one. But not all of them. It’s hard to imagine the Real Academia hosting a show such as Sensation (1997), which introduced Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and co. to a wider public.

It’s the mixture of very old and absolutely new that makes the RA so unusual. The route from Burlington House to Burlington Gardens now passes through the Royal Academy Schools, an important though previously hidden aspect of what the RA does. Dotted along the way are some of the RA’s fine collection of casts. These were a vital part of art education from the 16th century until about 1975, when many art schools threw them away.

Wisely, however, the RA kept theirs. It is, after all, a bit of a museum with an eclectic collection of things both wonderful and strange. Those in a new display include Michelangelo’s ‘Taddei Tondo’, one ofa tiny number of his sculptures outside Italy, and also an early copy of the cartoon for his lost painting ‘Leda and the Swan’ (this was apparently destroyed by one of Louis XIV’s mistresses for indecency, and you can see why if you look closely at what the bird is doing with its tail feathers).

Also in the vanished masterpieces department is a large, early copy of Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’. This is much clumsier than the original, but nothing gives a better idea of the rich, almost Flemish, nuance and detail that the now almost disembodied masterpiece would once have had.

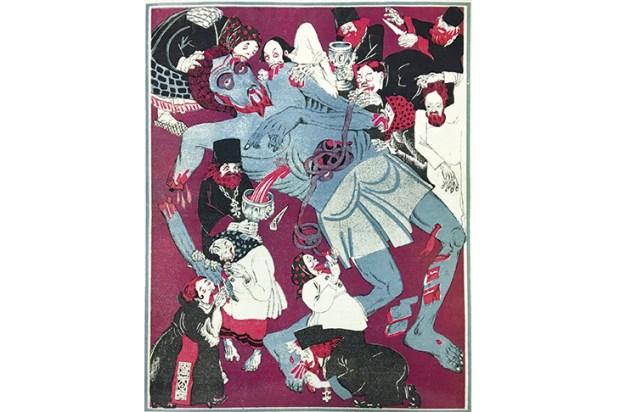

Among past Academicians, John Constable scores with a superb series of works, including a wonderful sketch of Somerset House — the RA’s first home, from 1780 — by night. In addition there are works by Gainsborough and Turner, among others, and a huge, fascinatingly bad Lawrence: ‘Satan Summoning his Legions’ — a pastiche of Fuseli that manages to make the original look tasteful.

From the start, precisely 250 years ago, the RA has always been noted for exhibitions — especially the annual one prominently featuring works by its members. But its current role, as one of the world’s major venues for retrospectives and surveys of the arts of all times and places, is relatively recent.

Its origins lay in a Spectator column of 1977. The arts editor, Bryan Robertson, commissioned Norman Rosenthal — then out of a job — to write a few pieces. In one of these he noted that the RA had wonderful galleries, but seemed to lack the vision as well as the funds to make full use of them.

This article made an impression on the president of the Academy, Hugh Casson, who circulated it to all the academicians.A little later Rosenthal was appointed exhibitions secretary at Burlington House and set about carrying out his own recommendations.

At that point, effectively, the modern history of the RA began. This week another phase has started. It is a moment to reflect on how easy it is to take the RA for granted, and how extremely lucky we are to have it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in