It’s not every day that a television screenwriter is threatened with a trial for sedition, but G.F. Newman was after his series Law & Order aired on BBC2 in 1978. ‘The political fallout was enormous and there was a move to try and get me prosecuted by Sir Eldon Griffiths and a gang of MPs, but it didn’t go anywhere,’ Newman remembers. ‘It would have been a wonderful case had it done so.’

Law & Order rocked the boat by doing the unthinkable, so much so that BBC director-general Sir Ian Trethowan was hauled over the coals by the Home Office minister John Harris (later Lord Harris). It depicted the police, legal establishment and prison system as interlocking components of a web of corruption, in which everybody was happy to feed off the illicit proceeds of crime and the police and thieves were two sides of the same coin. It made Newman’s point for him that the actors playing the policemen might easily have changed places with the villains.

‘Trethowan made a good argument,’ says Newman. ‘He said, “We have independent-minded producers and they make drama of the day and this is one of them.” But the show was banned and didn’t get sold anywhere in the world, and didn’t come out of the cupboard for 30 years.’

‘There was the most extraordinary uproar from MPs, from the Met, from the prison service, senior members of the BBC and the House of Lords,’ says its producer Tony Garnett, whose CV includes Cathy Come Home and many collaborations with Ken Loach (ironically, Garnett once appeared as an actor in Dixon of Dock Green, the epitome of television’s traditionally adulatory portrayal of the police). ‘How dare we tell these lies about our boys in the Met and so on. But a little later Robert Mark was made commissioner of the Met, and he said it was his ambition to arrest more criminals than he employed.’

In 1978, recent real-life revelations about corruption in the Met’s Obscene Publications Unit and Flying Squad gave Law & Order an additional jolt of contemporary relevance. Now BBC Four has been broadcasting it again on Thursday evenings, and despite being 40 years old it puts most recent crime series in the shade. Delivered in four 80-minute segments told from the overlapping perspectives of the police, the criminal, the accused’s solicitor and the prison service, it generates irresistible force not by stomach-turning stories of child abuse or horrific serial killings (themes worked to exhaustion in current dramas, from Line of Duty and Happy Valley to The Fall and The Missing) but by meticulous accumulation of detail. ‘It goes quite slowly so you actually think about things that are going on,’ Newman remarks. ‘TV now goes at such a pace that you think, I didn’t really understand that, but then you’ve got the next scene and the next car crash so you’re into that.’

The actors, especially Derek Martin as Detective Inspector Fred Pyall and Peter Dean as Jack Lynn, who’s cynically framed by Pyall, have a dead-bat naturalism that is compellingly plausible (both later became regulars in EastEnders). Seventies London looks dingy and dull, as if lit by a job lot of second-hand daylight that fell off the back of a lorry. The use of long zoom lenses draws the viewer into a shifty, illicit world. Meanwhile the complete absence of background music is almost physically shocking when all current drama series are drenched in sophisticated electronic sound-painting.

‘I don’t have music in films,’ snaps Garnett. ‘As soon as you hear a score you wonder, where’s that fucking band? You’re admitting that the dialogue and the acting and the photography aren’t good enough to create the emotional reaction you would like. Music tells you what you should be feeling — it’s a prop, and it takes all the realism away.’

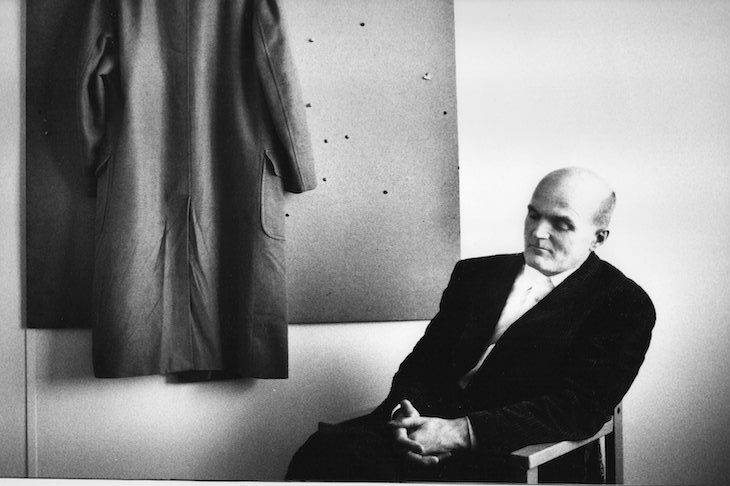

Garnett praises Law & Order’s director Les Blair for his ‘low-key manner’ and the way he ensured that the series ‘would be just quietly, even boringly believable’. Garnett also had rigid rules about casting. ‘I don’t want to see any acting! If you see any acting you’ve failed. I just want us to observe characters in the moment.’

It wasn’t long after Law & Order first aired that the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) introduced new rules governing the way police could use their powers, but how much really changed? ‘A lot of things have been cleaned up, but I’m not claiming that our films achieved any of that,’ says Garnett. ‘I used to think “we’ll make a film and change the world”, but that was the arrogance and optimism of youth.’

As for Newman, he used to say that 90 per cent of police were corrupt. And now?

‘What has happened in our society to make people less corrupt, and are the police somehow not affected by corruption?’ he retorts. ‘So I think they probably are as corrupt.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in