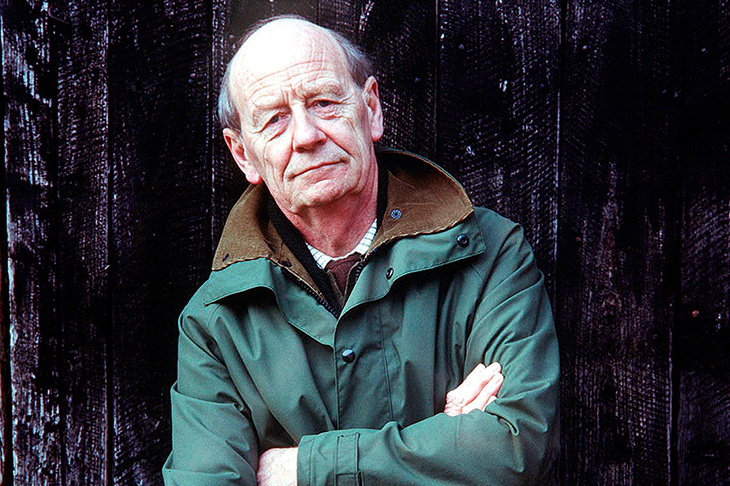

A very prolific and long-standing writer of short stories reveals himself. William Trevor, who died in 2016, owned up to 133 short stories in the two-volume 2009

Collected Stories, and here are ten final ones, written in his last seven years. One shy of a gross, he might have had a character put it.

Reading through them, we see occasional echoes and repetitions; characteristic ways of looking at life, and of putting a story together; a slowly emerging political stance; a turn of phrase; some favourite words; a delight in sentences. The novels are splendid. The sequence from The Boarding House to Other People’s Worlds hardly misses a step, and The Children of Dynmouth (1976) is a masterpiece. But the stories are many and multiple, and give us a more total sense of Trevor. The more facets a solid object has, the more rounded it appears.

Trevor had a pungent literary personality that emerged in all sorts of minor ways. His names have a particular flavour — Mulvihill, Belhatchet, Frobisher, Thrive, Torridge, Unwill, or (a particular favourite of mine) Peggy Urch. Somewhere between Mervyn Peake and Victoria Wood, they seem perfectly possible, and even to reflect a respectable antiquity. And yet after a while one realises that one’s probably never met anyone with any of these names.

The same is true about the trappings and labels that flit through Trevor’s work: a character is brought up short by the revelation that someone called Olive Gramsmith is rumoured to be ‘a slapparat, whatever a slapparat was’; or that their mistress is cooking ‘a nice fresh mackerel in a custard sauce’. (‘He imagined he must have heard incorrectly: he could not believe that the sauce was a custard one.’)

That territory, of the strangeness of possible behaviour, is Trevor’s own. He is fascinated by the moments when rules of behaviour are decisively broken. A recurrent scene is of a respectable person conversing with somebody who veers dangerously out of control. Loss of temper is loss of face, and the demonic presence often wins the game, leaving chaos in his or her wake.

Trevor is an acute observer of the sort of rules that people obey without knowing that they are doing so. Office life, and institutional behaviour, provide some of his richest material; but he often writes with joyous aplomb about the sort of rules that govern the exchanges between strangers at a cocktail party (‘Raymond Bamber and Mrs Fitch’); between a juvenile customer and a waiter (‘Going Home’); or an abandoned wife and a new mistress (‘Running Away’). Those rules become apparent to us once they are broken, by, for instance, an acquaintance starting to talk over dinner about the sexual culture of school in the long distant past. The results can be extraordinarily violent: three families lie in ruins at the end of ‘Torridge’.

At his best, Trevor is very far from the tactful restraint that is sometimes thought to characterise the short story as a form. His are crowded with people. Many, including ‘Torridge’ and the sublime ‘Mrs Silly’, have more than 30 named characters. He is rude and indecorous; he is fascinated by the wilder shores of sexual excess, from amateur pornography (‘Mulvihill’s Memorial’) to drug rapes (‘Kinkies’) to rough trade (‘Timothy’s Birthday’) and lesbian obsession (‘Flights of Fancy’). One of his greatest, ‘Angels at the Ritz’, extracts a mood of great tenderness and regret from a frankly lurid account of a wife-swapping party.

He loves stories rooted in alarming turns in social behaviour, such as underage sex in the playground (‘Nice Day At School’) or juvenile delinquents and irresponsible social workers (‘Broken Homes’). Rereading him, I wondered at the mysterious fate that has condemned Kingsley Amis in liberal opinion and sanctified William Trevor: the social attitudes underlying Other People’s Worlds or the story ‘Afternoon Dancing’ might easily raise a bien-pensant eyebrow. But the richness of observed life is unforgettable. Like most great writers, he is not really there to be agreed with.

And it’s worth remembering just what a superb writer of short stories Trevor was, because we might as well admit straight away that this last volume shows something of a falling off in quality. Some of the stories are sad little diagrams. ‘The Piano Teacher’s Pupil’ is about a woman who accepts that she will be stolen from by her most gifted pupil, but hardly fleshes out an implausible exchange. ‘An Idyll in Winter’ and ‘The Unknown Girl’ both pluck a great passion out of nowhere, and the characters involved are hardly there.

One recurrent problem is that Trevor had slightly lost touch with the worlds he was describing. This had been foreshadowed in his later Irish stories, which had started to be most convincing when they talked about the Ireland of past decades. Here the inevitable detachment from contemporary life is quite general. I just didn’t believe in his idea of a stylish London café in ‘At the Caffé Daria’; and his setting of a contemporary London ‘neighbourhood that had been fashionable but no longer is’ proved difficult to imagine. His stories had been thinning out in texture for some time: a late story, ‘The Potato Dealer’, suffers from being so much less populated than a classic such as ‘Angels at the Ritz’. Some of these last ones are even sparser, while rather disastrously maintaining Trevor’s best subject: of how an individual can connect a wide segment of society. ‘The Unknown Girl’, with its five characters, one of whom is dead, could never have worked.

There are, however, two or three stories with the old gleeful panache. In ‘Making Conversation’, a girl is visited by the aggrieved but pathetically misinformed wife of her stalker — a situation inspired by an episode in Howards End, but vividly done. ‘Taking Mr Ravenswood’ is a sinister exploration of the relations between a rich benefactor and a young married couple. It is one of Trevor’s best subjects, as in the classic ‘A Trinity’, and the husband in this is also called Keith. Here, the question of who is extracting most from the situation is kept beautifully floating. ‘Mrs Crasthorpe’ has a situation of intriguing force, even though the execution is somewhat elliptical.

There is no doubt that William Trevor was one of the great writers of short stories. During his best period, he produced a couple of dozen of astonishing force and unique flavour. The two-volume Collected Stories is a joy to read through. Though, in the interests of truthfulness, I can’t pretend that these last stories are all masterpieces, Trevor’s was a long and prolific career, and the quality and variety were sustained for most of it. What his reputation rests on remains formidable.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in