Midnight in Shoreditch, and snaking round the brickwork of old east London is a line of chattering clubbers. Everyone seems to be queuing for something here: a new restaurant, or a new microbrewery. Inside the club, hipster students, bearded professionals and wealthy tourists fill the dance floor.

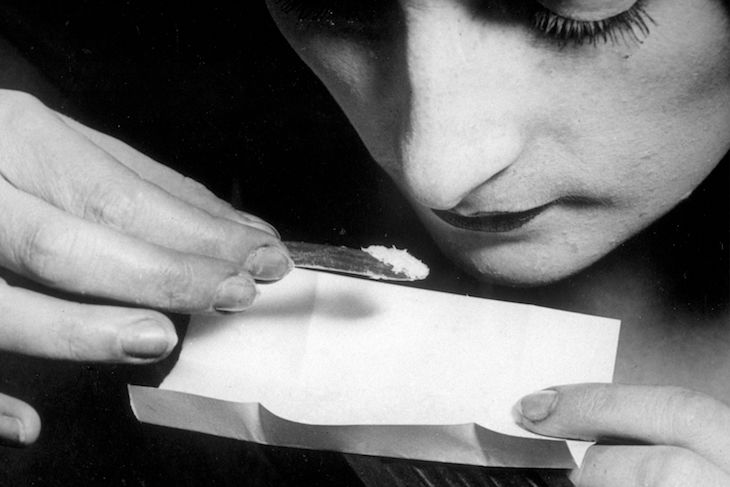

I easily spot the drug dealers weaving in and out of the throng, full of entrepreneurial determination. Conspicuous, too, is the queue of clubbers waiting for the toilet. I feel a tap on my shoulder. ‘Mate, need any gear?’ I glance down to a hand clutching a bag of powder. I tell him I’ll pass, thanks. He doesn’t look disappointed; business is good.

Two miles up the road in nearby Hackney, there were several more stabbings last week. The number of Londoners killed by violent crime this year has reached 62 — 37 of whom have been stabbed to death. Crisis levels. Most of the victims are young, black and at least peripherally connected to gangs who make their money selling and trafficking drugs. The capital’s voracious appetite, especially for cocaine, has more than a small role to play in the deaths of these kids, yet it is rarely asked: who’s buying the cocaine that fuels the drug wars?

The answer is, exactly the sort of British men and women who pride themselveson being more ethical than previous generations. More than 4 per cent of all 15- to 34-year-olds in the UK confess to using cocaine in the past year, twice as many as in the rest of Europe. And that’s just those who admit it. To get the true measure of UK cocaine use in you need only look at the sewers. London has the second-highest level of wastewater cocaine residue in Europe, at 900mg per 1,000 people, way above third-place Barcelona. London falls just behind Antwerp, a port city with direct trade links to South America.

The Home Office estimates the illegal drugs market to be worth £5.3 billion. Last month, three drug dealers were jailed for transporting £4.5 million of cocaine across London in a holdall. According to the Global Drug Survey, the good stuff can be delivered to a Londoner faster than a pizza, with a third of users able to get their hands on the drug within half an hour. Frequent users can even use a cocaine loyalty card (‘buy five and get a sixth free’) — this is a product marketed and distributed with laudable professionalism. Buying cocaine is the easiest it has ever been, even for the casual user; 34 per cent of buyers purchase it through friends and 48 per cent from known and trusted dealers.

Our hospitals are feeling the effect of this growing popularity. Last year there were 12,000 admissions suffering from ‘mental and behavioural disorders due to the use of cocaine’, more than double the figure ten years ago. The figures show our capital has a problem with cocaine that’s rising in step with the knife-crime epidemic. Young white professionals are contributing directly to the culture that leaves black kids dead.

What’s strange is that they understand the problem. They’re educated. They grew up in the wake of the Colombian cocaine boom that devastated cities such as Bogotá and Medellin. More often than not they’ve travelled widely and think of themselves as defenders of human rights. These are the same people who buy fair-trade coffee and agonise over the conditions animals are kept in. They don’t wear fur, sometimes they’re fashionably, and loudly, vegan — but a gram of coke is as much an essential part of a night out as a selfie in the loos.

Yet gang culture remains an issue greeted with silence by the fair-trade generation. The killing of black boys fails to make the grade as a popular issue. But why? Perhaps it’s because to crack down on crime you’d need to support the police, and that’s not likely to happen. Perhaps it’s because we’re not used to depriving ourselves of things we actually want.

It’s also because cocaine is a gentrified drug. Sheltered middle-class users are drawn to the convenience and discretion of its complex delivery systems using encrypted social media and the dark web, a far cry from the days of the shady alleyway drug dealer. Cocaine dealers are now more likely to be middle-class and presentable, meaning the user never comes into contact with a gang member from an estate. The slick means of getting it from dealer to customer has sanitised the act of drug-taking, sheltering the middle classes from the unpleasantries involved in getting cocaine to them.

‘I just didn’t make the connection,’ a friend tells me with contrition, keen to stress his newly reformed character. ‘Coke is just like drinking alcohol on a night out. A friend of a friend might be selling it, raving about how good his batch is. Which is funny — we’re not interested in how the drugs come to be in our possession, but we really care about their quality and purity. We’ve become connoisseurs.’

I confront another friend on the subject, who looks taken aback before gathering her senses. ‘That’s why I stopped,’ she quickly assures me. ‘Ultimately, there isn’t a way to use coke ethically, but many of us aren’t willing to give it up, so we justify it by thinking, “My dealer is a nice guy” or “Well, gangs would still exist regardless of me.”’

‘Really?’

‘Definitely.’

It’s illogical because it’s selfish. It’s amazing — our capacity to stop caring just in order to have a good time.

Now listen to Alistair Thomas talk to Isabel Hardman and Dr Adam Winstock, head of the Global Drugs Survey, on this week’s Spectator Podcast (13:20):

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in