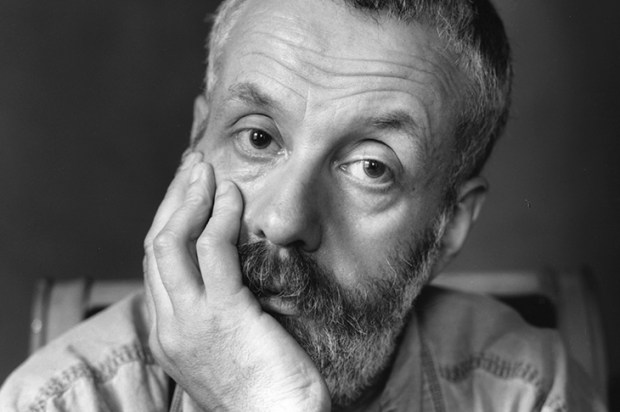

Antony Gormley has replicated again. Every year or so a new army of his other selves — cast, or these days 3-D fabricated, in bronze, iron, steel — emerge from his workshop. Some lucky clones find themselves in wild and beautiful places; others are trapped in private collections.

The latest clutch, generation 2018, find themselves in the new galleries at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge (until 27 August), one sticking out horizontally from a wall, another, an airy stack of steel bars, staring down through a window into town. It’s called ‘Subject’, this work (also the title of the exhibition), and Gormley’s intention is that it acts as an invitation to each gallery-goer to pause; to become aware of themselves as subjects too. These are not figures, so goes the idea, but representations of, and triggers for, an interior mental state.

Well, ‘Subject’ has made me aware, but perhaps not quite in the way the artist intends. I like Antony Gormley. I interviewed him once for this magazine and found him charming. I admired his Turner Prize-winning ‘Field’. But I’m increasingly sure that his big idea works far better in theory than it does in practice. In fact, I strongly suspect that the great diaspora of Gorms often has the very opposite effect on a viewer than the one its maker intends.

Take Gormley’s 2015 series ‘Land’, five life-size Gorms positioned in five different watery locations around the UK. One still stands, contemplating the Isle of Arran across the Kilbrannan Sound, thanks to an anonymous donor. Again, they’re intended as a poke in the ribs. Like the parrots on Aldous Huxley’s Island, they remind us citizens to stop, look, to be ‘here and now’. But if you’ve travelled to the Kilbrannan Sound, with picnic and a pac-a-mac, aren’t you exactly the sort who doesn’t need to be told? And, isn’t it irritating?

Yes, we enjoy the unexpected: a rusting robo-man on some unexpected outcrop. But when the surprise fades, it quite spoils the more magical feeling of having discovered a place oneself. Because it’s a figure, it becomes company — and in company that very sense of lonely interiority that Gormley’s trying to invoke evaporates.

Gormley can insist his body-casts are not figures; that a sentimental reaction isn’t appropriate, but is that in his gift? If you’re going to state, very clearly, that the viewer is part of the art form, then his views matter too, and we’re animists as a species, incorrigible anthropomorphists. We project personality on to cars. The Gorms don’t stand a chance.

Modern figurative sculpture can work very well — it’s not the art form that’s the trouble, I don’t think. Look at the work of a less famous contemporary of Gormley’s, John Davies, neither knighted nor an OBE. Last year, as Gormley’s cast-iron self left the Ondaatje Wing of the National Portrait Gallery, a troupe of Davies’s near life-size figures materialised in the Turner Contemporary in Margate. ‘My Ghosts’ they were called — a pantheon of lopsided, shadowy, strange figures. Perhaps because they weren’t aiming to be signposts, or universal signifiers, but quite particular characters from Davies’s personal past, they glowed with universal meaning. Interestingly, it was impossible to feel sentimental about them. They had too much personality of their own.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in