Imagine you are responsible for educating the children of China’s current leaders, many of whom may well go on to be future leaders themselves. What would you teach them?

This isn’t, by the way, some sort of abstract philosophical argument or hypothetical.

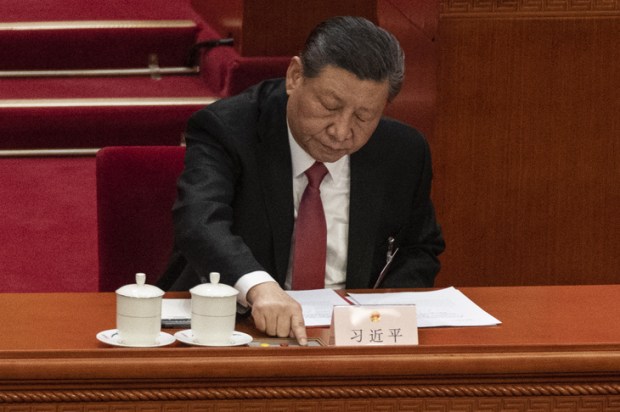

This year over 170,000 students from the People’s Republic of China will be enrolled in Australian universities. President Xi Jinping’s only child recently spent time as an (anonymous) undergraduate at Harvard. There are almost certainly sons and daughters of senior Chinese government officials studying on Australian campuses right now.

This influx of mainland Chinese students has recently been presented in the press as a potential threat to the independence of our universities. If not handled appropriately it could be.

But fact that we now have under our direct tutelage significant numbers of young students from the new powerful economic and military colossus to our north should also be seen an enormous opportunity to exert positive influence. It is a David and Goliath battle to be sure, but you never win by only playing defense, and this captive audience of China’s best and brightest should be an incredible tool at our disposal.

Unfortunately, the sad reality today is leaders in Beijing can send their offspring to leading western tertiary educational institutions confident that they will not have their worldview – economically, spiritually, or politically – seriously challenged.

The thinking at our universities simply shares far too much in common with their counterparts in Beijing to be a means for real change.

Our universities claim to be in favour of free speech, but their attitude is in practice very different.

As a recent report from the Institute of Public Affairs (Free Speech on Campus Audit 2017) details how debate on important political topics is being curtailed through the use of speech codes, venue cancellations, law suits, and outright censure of academics.

Our universities claim to be in favour of open scientific enquiry, except when it differs from the party line – as the recent sacking of James Cook University academic Professor Peter Ridd for his dissenting views on the impact on climate change illustrates.

Above all, Australian universities share a deep-seated hostility to the idea that they should be teaching the superiority of Western civilisation to their students. The recent controversy regarding the proposed introduction of a new degree in Western Civilisation at the Australian National University, promoted and financed by the Ramsay Centre, is just the latest example of a long-running dispute in this area.

‘Never let textbooks promoting Western values appear in our classes,’ China’s former education Minister Yuan Guiren declared. ‘We must, by no means, allow into our classrooms material that propagates Western values’. His views could well be written on material issued by the National Tertiary Education Union.

It is however important to properly understand what Beijing means by ‘Western values’, because to a large degree it is what our own universities object to also.

The Chinese Communist Party has no problem with particular types of ‘Western’ material.

After all, it owes its very existence to a book written by a German Jew in a British library in the 19th Century. Xi Jinping recently described Karl Marx (who is self-evidently not Chinese), on the 200th anniversary of his birth, as ‘the greatest thinker in human history’. Various strains of Marxist theory (some explicitly labeled, other less so) are taught widely in universities in both China and Australia.

Chinese leaders are not even concerned about thinkers from the European ‘Enlightenment’.

Schools in Beijing often contain statutes of secular saints of the ‘Age of Reason’ – people such as Charles Darwin, Auguste Comte or Jean Jacques Rousseau. Documentaries on ancient Rome and Greece are regularly screened on Chinese TV. Works by everyone from J.K. Rowling to Patrick White to Bill Gates and Simone De Beauvoir can be found in university bookstores and libraries.

No, when Beijing refers to ‘Western values’ what it is really concerned about is something more specific. What they really mean is Christianity and the values that flow from it.

Christianity can be taught and tolerated as an interesting anthropological phenomenon, of course, but under no circumstances should it taken too seriously especially by those in the ruling class.

Thus it has long been in universities in the West.

William Buckley Jr. in his famous God and Man at Yale, which is credited with creating the modern conservative movement in the United States, diagnosed the problem over 60 years ago.

His argument was not that universities should be turned in to seminaries. They should encourage open debate on all manner of subjects. But they must also have a sense of mission beyond simply ‘we can teach whatever we like’.

That mission must seek to impart to their students a sympathetic understanding of ‘faith, freedom and family’, a combination of words you are as likely to hear out of the mouth of a Beijing apparatchik as an Australian university administrator. Appeals to ‘academic freedom’ in this context are as self-serving as those of the Australia Broadcasting Corporation’s left-wing hacks decrying ‘journalistic independence’ whenever they are criticised.

The most important questions for any society, Plato thought, were: Who will teach the children? And what will they teach them?

How we answer matters not only to the type society that we want to build here in Australia, but has great importance – more than perhaps many realize – to the society that China will become as well.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in