It’s not a wrap. This is the first thing to note about the huge trapezoid thing that has appeared, apparently floating, on the Serpentine Lake. Many of the projects by the artists who conceived it, Christo and his late wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude, have involved bundling something up in a temporary mantle. The items thus packaged over the years include a naked woman (in Düsseldorf, 1964), the Pont Neuf (1985) and, famously, in 1995, the Reichstag.

This London work, however, is the product of an equally long-running obsession with the barrels in which oil is stored and transported. At first, and second, glance, these objects lack charm. Nonetheless, the youthful Christo — a Bulgarian who fled the communist regime and settled in Paris — used to lug them up the stairs to his top-floor studio.

There he arranged them into simple minimalist sculptures resembling pillars. Sometimes he would wrap them in cloth (a selection of these early efforts is on show in a concurrent exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery). These failed to sell and the artist threw many away — not a great loss on this evidence. But then Christo had not yet worked out what to do with his barrels.

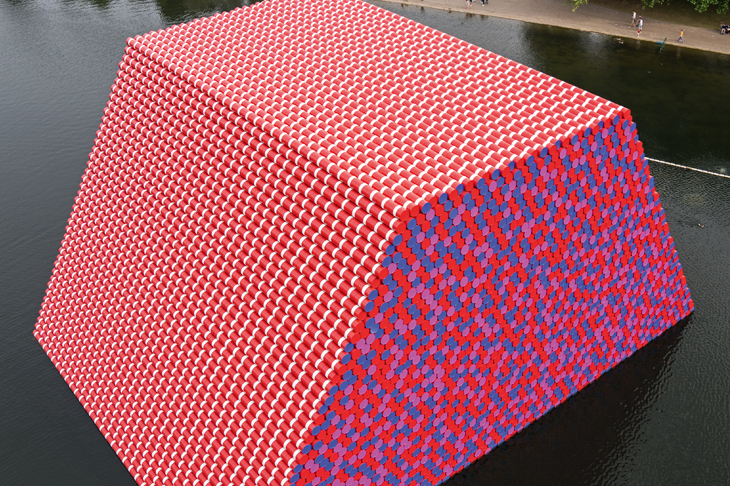

Soon after, he added an extra ingredient — colour — and thought of piling them up in the real world outside his studio. Beginning in a small way, he blocked a narrow Parisian street with a barricade of the things (the police asked him to take them away, which he did). But from the 1970s, he and Jeanne-Claude proposed a series of much more imposing structures composed of row after row of barrels, laid on their sides to make an oblong mass with sloping ends and a flat top.

There is a plan to place one of these so-called ‘Mastabas’, which would be almost 500ft high, in the desert near Abu Dhabi. If it were ever to be built, this would be rather bigger than the Great Pyramid at Giza. Not altogether surprisingly, it is still at the project stage. Indeed, the ‘London Mastaba’ is the only one, to date, that has actually been made (plans and drawings for others are on show at the Serpentine).

It has divided opinion. A millennial, admittedly of a rather conservative turn of mind, told me he thought that it was an expensive way of spoiling a good view (Christo, by the way, paid all the costs as he always does). Another critic who often loves avant-garde things compared it to an oversized bath toy. I maintained an open mind until I reached the Serpentine bridge, looked over the water and saw it glittering in the sun.

I loved it. It is, I think, partly the meaninglessness that appeals. When you first hear about the oil barrels, it is easy — if you are used to decoding modern art — to sketch a suitable message: fossil fuels, climate change, oil money, energy crunch. But, it turns out, Christo isn’t interested in any of that stuff. Nor is he concerned with the usual sense of ‘mastaba’: that is, an ancient Egyptian funeral monument. Instead, he points out that early Middle Eastern cultures made street furniture in this form. My guess, however, is that he just likes the shape — and the fact that you can make it by stacking cylindrical units up and up, without them tumbling down.

What makes the Mastaba succeed is the sheer improbability of this enormous, Babylonian-looking edifice in the middle of London. It seems unreal, if not surreal, and the colours — purple, orange, red — make it shimmer like a 3-D Bridget Riley. If it were made of unpainted barrels, it would look horrible. And any meaning would spoil it.

It’s much the same with the mysterious little paintings of Tomma Abts, which are on display a few yards away at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery. These are what used to be called ‘abstract’, though the painter doesn’t like the word. Her pictures, she claims, start off abstract then get more specific.

Abts — who was born in Germany, but lives in London — has painted a small number of these over the past few decades, very slowly. They are all the same size and close to indescribable, though I will have a go. One called ‘Lüür’ caught my eye (and not only because its title contains two umlauts). It consists of a slightly grungy lime green surface on which there is a skein of something flexible, the loops of which sometimes cast a shadow, as if it were, say, a ribbon on a tasteless tablecloth. Why depict such a thing? If there’s a reason, Abts isn’t saying what it is. But the painting sticks in the mind, prosaic yet strange. Memorable pointlessness: perhaps this is a new movement in art.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in