Christopher Howse has just written a book about Soho. He drank there regularly with Michael Heath, The Spectator’s cartoon editor, in the 1980s. Last week, in the editor’s office, they remembered a vanished world.

MICHAEL HEATH: I introduced you to Soho.

CHRISTOPHER HOWSE: Well, I don’t know if you’re entirely to blame for that. But you taught me a thing or two.

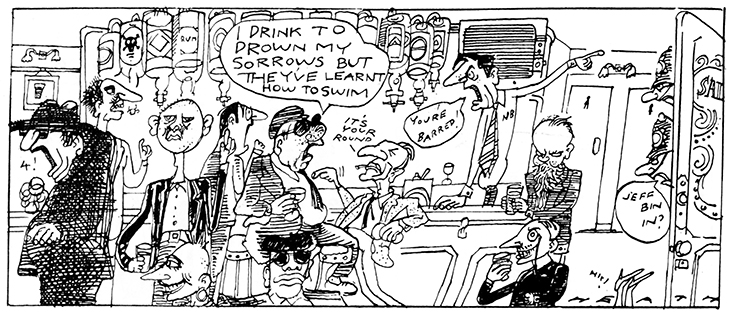

HEATH: There were such things as groupies for cartoonists in those days. There were girls hanging round you in Fleet Street waiting for you to finish the drawings for the following day and then they’d go off with the cartoonists and have meals or go to various clubs. The cartoonists were wealthy, really, because it was cash in hand. You couldn’t get a cartoonist who was stable. They didn’t have houses or anything like that because they spent freely. I came across a similar lifestyle in Brighton, where they were all criminals. I thought they were terrific fun, as long as you didn’t get on the wrong side of them. Some had razor blades stuck under their fingernails. It was very much like Graham Greene. They’d get angry and whack each other with billiard cues. The idea was to have a fight and you’d get whacked or slashed, claret would be all over the place. And they’d like that because it left them with a nice scar.

HOWSE: The barman at the Colony Room Club had a marvellous chiv right down his cheek. People would drink there because, until 1988, the pubs closed at three o’clock and didn’t open again until half-past five. What are you supposed to do until then? You had to spend the afternoon somewhere, so you had afternoon drinking clubs, the Colony Room Club being the best of them. They were all private members’ clubs, so they were perfectly legal. But there were some very nasty ones. There was one called the Kismet Club in Newport Street and it had two nicknames. One was ‘Death in the Afternoon’ and other one was ‘the Iron Lung’. It was underground with no windows, walls weeping with damp and bits of paint coming off them. The lavatory opened straight onto the bar with no intervening doors. It was run by a rather wonderful woman called Maltese Mary who knew what was what.

HEATH: Yes, the place where someone asked: ‘What’s that strange smell?’ Then gave the answer: ‘Failure.’ But the thing was, we all worked. It wasn’t like a crowd of drunks on a bombsite; you were surrounded by very intelligent people. These were professional circles; you had to come up with something to say.

HOWSE: The big sin was to be a bore, because then you were immediately victimised and your foolish remarks thrown back at you. Jeffrey Bernard used to introduce something that he was going to say with a phrase like ‘Do you know what your worst trouble is?’ and you knew it was going to come. Whereas Ian Board in the Colony Room Club would just go into a tirade of abuse that would last about 17 minutes. It didn’t happen to me because I defended myself by being weak and making jokes.

The Coach and Horses

HEATH: A typical day would start at the Coach and Horses when it opened at the stroke of 11. Jeffrey would be sitting at the bar at one end and two other people standing next to him, real serious old barrow boys…

HOWSE: Charlie Clarke. He was mixed up with that business where somebody’s head was found in a public lavatory. But he was quite normal. There was a stage door-keeper, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, called Gordon Smith. He was given the nickname Granny Smith because he was like an old grandmother. He wasn’t a bore and he wasn’t subservient, but he didn’t show off. He was just there constantly.

HEATH: One of the things you couldn’t do was boast. You could never suggest that you might be somewhat happy, or that things were all right. You had to be in a total state of panic and despair about something or other. There was a whole lot of us: intelligent people, but we had failed this, that and God knows what else. Even Francis Bacon, who was earning then £76,000 a painting — huge money. But you could never talk about money. We were all amateurs, starting out all over again. And fearless, when you think of the booze we shifted. I was doing an average of 15 large whiskies a day. My liver and I ended up having separate bedrooms.

HOWSE: You didn’t show it. You never gave any signs whatsoever of being drunk. I drank a good deal too. We had drink in the office and we had drink in the pub, so it would go on from day to day. But some people were just astonishing drinkers. There was a man there called Bill Moore, he was a driver, of all things, God help us. He used to sit there at the bar with his sweater on and he would just sit there drinking double Bell’s whisky until it was closing time, then he’d drive home or drive to France or whatever it was.

HEATH: At opening time Jeffrey Bernard would be in the corner. Nobody’s saying anything. Jeffrey would sit there doing some terrible coughing, nose-blowing and all the rest of it. Then he’d have his first drink and he’d start telling some awful story, always to do with something of his rotting or falling apart.

HOWSE: Or somebody being decapitated by a helicopter.

HEATH: That’s right. ‘Somebody parachuted down from a plane and landed on a helicopter rotor. Can you imagine the noise and the filth and the smell…?’ Anyway, these three or so men just drank and drank. You’d go up and be involved in it, so it was your round and you’ve got four people to buy for. Then another person comes in and then he buys a round and so that’s five people. You couldn’t escape without being in serious trouble.

HOWSE: It was just great fun, despite the misery. It was funnier than any situational comedy could be, because you knew all the people. The things that happened were astonishing and it always ended in tragedy, breakdown of health, falling down the stairs. Death — that was the automatic ending. But in the meantime it was great fun.

Francis Bacon

HEATH: At some point Francis Bacon was bound to turn up. When he did, every-one jumped up and started hanging around him because he was enormously famous, even then. My feeling about him drinking is a bit odd, because he certainly was drunk some of the time. But he mainly got other people pissed. I think he liked seeing people falling apart. Though by the morning, I’d see him hanging on the bandstand.

HOWSE: Yes, he did get completely pissed. He used to speak in this very Cockney camp way. He was picked up for being drunk and disorderly in Old Compton Street and as he was put in the back of the Black Maria, he said to the constable: ‘I’m a very fime-ous pine-ter!’ There was always that air of terror with him.

HEATH: He had a doctor work on him because he liked being beaten up, seriously and regularly.

HOWSE: For sexual purposes.

HEATH: Seriously beaten up. I was told the doctor had to put his eyeball back in once the following morning.

HOWSE: Marge Dunbar, a great friend of mine, she said that Francis Bacon was the funniest person she ever knew. She thought John Minton was great fun. He was a painter.

HEATH: Ruined by Francis Bacon.

HOWSE: Minton killed himself at the age of 39.

HEATH: Francis killed many people, just with words. Minton was doing very well after the war. His drawings would sell well to magazines and he was quite a star. He mixed with Francis and drank with that mob. Francis, when he was asked what he thought of Minton’s work, said: ‘He can’t paint. He’s a book illustrator.’ That went straight into Minton. He just gave up. Francis was always cutting when asked what he thought of people. Some could not take it. I knew people who’d been destroyed by a few words.

Falling in love

HEATH: I kept falling in love. I fell hopelessly in love with three women who all ruined me and took everything I had. But that was something to do with whisky, I think. There were a lot of women, but there’s something about their constitution. They can’t drink the way men can. They started the day with the rest of us and drank white wine and they’d be very jolly and sexual and all that, and by four o’clock they’re all crying.

HOWSE: It doesn’t do me much credit, but I’m afraid I was just an observer. I was a little bearded camera in the corner just fascinated by all these people. There were one or two whom you didn’t make jokes to. There were some pornographers who were quite dangerous, weren’t they? People were very disinhibited. John Hurt used to come to the Coach and Horses because he liked conversation and also because he got drunk there. And one Sunday evening he was so arseholed that he stood up on the bar. He was going to throw himself off as if he was crowd-surfing into the bottles and glasses on the back wall. It was going to be disastrous — he would have been cut to ribbons — but somebody had the presence of mind to catch his legs before he did it. Nobody made anything of it. And even though he was a very famous actor it never made it into the press, because you wouldn’t bother.

Jeffrey Bernard

HEATH: We were all in the same boat. We were a mess. People were rude and horrible and outrageous, but they were fun, original, and their like does not exist anymore. With Jeffrey Bernard it was different. I couldn’t keep up. He used to say to me: ‘You haven’t got any guts!’ And I realised that you had to be pretty fit to drink yourself to death in Soho. Good-looking, nice, charming women would fall in love with him and they’d marry him. They didn’t seem to realise that they weren’t going to go the theatre, that they weren’t going to the cinema, just the pub. Occasionally they’d go out with him to dinner but he’d fall asleep in his soup, so it wasn’t romantic in any way. But the women kept coming back.

HOWSE: They thought they could save him, literally, from death.

HEATH: In the end, he decided to commit suicide and invited me to do it with him. Well, not to commit suicide but to have a meal with him in his horrible flat behind the King of Corsica. It was like a huge ashtray. He smoked continuously.

HOWSE: And his artificial leg was standing in the bath, unused. He never had the strength or determination to use it. Next to that was a bucket full of under-clothes swimming around in disinfectant.

HEATH: I went up with him to the ashtray flat and there were two women there. They specialised in coming to look after him and bringing him the most expensive stuff from Fortnum & Mason to eat. And he’d mumble something rude to them, but they didn’t mind that at all. He’d eat all this food he wasn’t allowed to eat. He was on dialysis. He’d lost a foot and the other one was due to be taken off and he couldn’t take it any more. We sat there and choked while he ate all the wrong food, like Chinese, and drank all the booze he wanted to drink, vodka and stuff like that. Then he got these huge morphine tablets, and in front of us downed about eight and crashed. We carried him to bed, sat with him a bit until midnight when he woke up and said, ‘I feel great’ and then went back to sleep. I left and he died at about three in the morning. Sad endings.

A vanished era

HEATH: The idea in the war — blackout and everything else — was that everyone drank on the assumption it would be their last day. Women would sleep with men even if they loved their husbands. I’d grown up with that. You had American sailors, for God’s sake. Women would do anything to be with Americans. The clothing was enough to drive you mad. They had gabardine and aftershave. It was unheard of here. We were all walking around in mouldy old tweeds. And it sounds awfully soppy, but there was this decency about it. You needed some sort of class, regardless of what social class you came from. There were still criminals then. They did do awful things — you could be nailed to the floor and things like that — but still decent. The general malaise that we have now, depressing beyond belief, is the result of inertia and dim television. Mobiles have ruined our lives.

HOWSE: Everything’s changed. The difference was, and I’m not sure how healthy this was, but very odd people — they all sound like monsters, the way we talk about them — they did regard it as home. When Oliver Bernard, Jeffrey’s eldest brother, ran away at 16 just before the war, he found himself at home in Soho. People lent each other shillings and spoke about poetry and things that mattered; they didn’t talk about salaries and so on. One can’t idealise it, but there was something remarkable about the difference.

HEATH: I’d apply it here at The Spectator. Quite a few of the people we’ve been talking about worked here. I got Jeffrey Bernard into The Spectator. He did a racing column and then started the Low Life column. But that whole world we’re talking about has gone, vanished. And as far as we can gather, it can’t be resurrected.

HOWSE: I don’t think it can be. It would be nice to see something taking its place.

HEATH: On the whole, most of the people had an education and were very bright. They knew about things. I had no education, but I still knew what was what. You could make jokes about this, that and the other; make references to things. There was this assumption you should know about things, in a way that is different now.

HOWSE: People had stocked minds. They knew about poetry and art from having read and seen them, not from having looked them up on their mobiles. It’s a different way of thinking. It’d be marvellous to get some of the dreary management types you get now and take them back 30 years and put them in the Coach or the Colony Club. It wouldn’t make a man of them, but it might just make them think.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in