Yes, Oscar Wilde never wrote it. No, Strauss didn’t intend it. In fact, the composer famously demanded the Dance of the Seven Veils be ‘thoroughly decent, as if it were being done on a prayer mat’. But that doesn’t stop this striptease and musical money shot being the look-but-don’t-touchstone of any Salome.

A blonde, blank-faced Barbie doll in gym knickers, vest and shiny trainers stands in a spotlight, a baseball bat in her hands. Strauss’s oboe begins its suggestive arabesques but Salome remains quite still, her eyes fixed impassive, unblinking on the audience. Eventually her hips begin to twitch, her back arches and she goes sullenly through the motions of sensuality, never breaking her gaze, defying us to find her desirable. A squad of identical nymphets join her, their provocative movements calisthenic, robotic — a seduction routine choreographed for the Hitler Youth. It’s kinky, queasy and utterly compelling — a male fantasy seen through female eyes, a fully clothed striptease that leaves its onlookers naked and exposed.

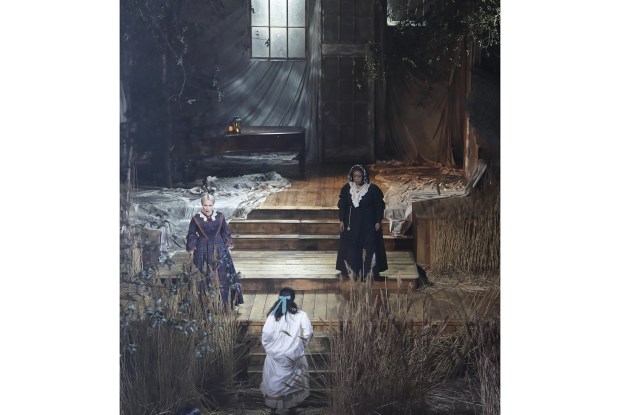

Taylor Swift; the Chapman brothers; Suicide Squad; Nicki Minaj; Lolita; Berlinde De Bruyckere: the references just keep coming. Australian director Adena Jacobs’s new Salome for English National Opera is a mess — a ragbag of undigested images, identities and ideas, a jigsaw puzzle without a solution, a collage of chaotic visuals. It’s not coherent, but how many teenage girls are? Especially ones lusted over by their stepfather and neglected by their narcissist mother.

This 21st-century Salome tries to tell her story using only what society and a screwed-up family have given her, a traumatised child trying to show us where he touched her using only a doll and a bright pink crayon. With no adult language of her own, she takes the toys and tropes of childhood, bends, brutalises and twists them into newly disturbing shapes.

Herod becomes a cross-dressing Father Christmas, first discovered half-naked in a tangle of teenage limbs; a life-size, headless My Little Pony is beaten like a pinata and gushes floral entrails; a bat becomes a weapon, candy pink the colour not of hearts but of blood. People are not inviolate either, broken down and stripped for parts. The prophet Jokanaan is reduced to just a mouth, projected vast and alien on to the wall, while Herod’s cheerleaders have their faces masked — bodies alone. Lovesick Narraboth comes off worst, chopped into fleshy pieces and eaten by the object of his desire. (Not so much a spoiler as a health warning to say that this production adds cannibalism and possibly incest to the story’s original necrophilia.)

But where does all of this leave Strauss? Somewhere under the visual clutter there’s a deliciously thrusting, brutal account of the score conducted by Martyn Brabbins. He’s not helped by voices a couple of sizes too small, but such is the skill of Allison Cook’s Salome (a mezzo woman-child of dangerous assurance) that she projects dramatically what she cannot quite musically.

Michael Colvin’s Herod is all querulous need and crazed desire — fluting his grubby requests with Peter Pears-style precision — though it seems a missed opportunity for him to have so little interaction with Susan Bickley’s cipher of a Herodias. Bass David Soar is miscast as Jokanaan, a high-lying role that here feels pinched and strained rather than exuding Old Testament authority.

A programme note promised us ‘confrontations with the abyss of the feminine’. I still have no idea what that means, and — more importantly — I’m not sure Jacobs ever figures it out either. Far from confronting the abyss, this production trips over its trailing skirts and tumbles into it. A fascinating failure, but a failure nonetheless.

If Salome is a work of the few, a claustrophobic close-up, then Memorial is a drama of the many. Alice Oswald’s beautiful, brutal poem — a litany of human loss — takes readers through every one of the deaths in Homer’s Iliad, each an epic compressed into a single image, a sentence, or sometimes just a name. Adapted into a music-theatre piece by director Chris Drummond and choreographer Yaron Lifschitz, it places a single voice — actress Helen Morse — at the centre of a silent, 200-strong chorus, singing their story with their bodies.

If Memorial left it at that it would be a triumph. The miraculous Morse — clear-sighted but infinitely compassionate — simply reciting the poem on a bare stage would be mesmerising. The addition of a score by Jocelyn Pook, however, is an overreach. Allusive, emotive orchestration (including a shawm, Celtic harp and beguiling Macedonian singer Tanja Tzarovska as well as more familiar forces) places us somewhere between ‘Adiemus’ and Hans Zimmer’s Gladiator soundtrack, and the endless ostinati borrow Philip Glass’s processes without retaining his precision. Oswald’s lightfooted verse finds itself shackled in banal melody, repeated to meaninglessness.

Oswald’s Memorial is a meditation on waste, on war’s human profligacy, its violent excess. What it needed on stage in this first-world-war anniversary year wasn’t more, it was much, much less.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

![A woman-child of dangerous assurance: Allison Cook as Salome in Adena Jacobs’s new production for English National Opera. [Catherine Ashmore]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/6Octopera.jpg?w=730&h=486&crop=1)

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in