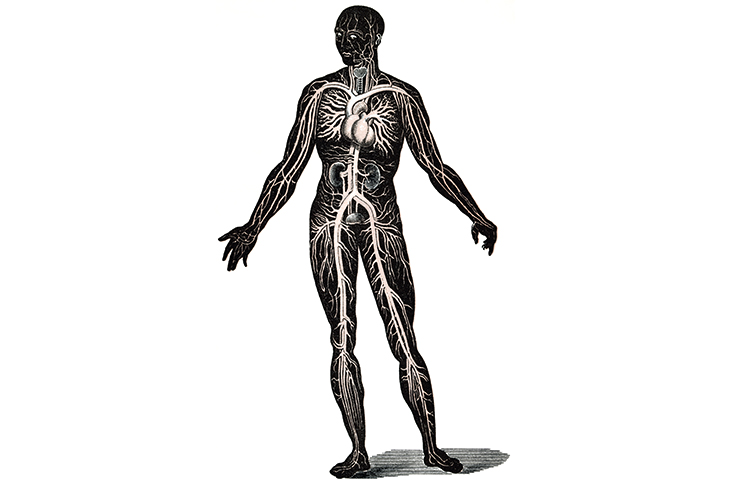

The numbers invite awe: three billion beats in a lifetime; 100,000 miles of vessels. But on the hospital floor, wonder is often in short supply. Doctors forget how intimate their examinations and investigations can be. Stethoscope to chest. Order a blood test.

I remember on a morning ward round at medical school, our consultant wanted to check that the oximeter was working (a device which measures heart rate and blood oxygenation through the nail bed). He asked a harassed junior doctor to present her forefinger. The screen’s digits betrayed her stress levels. She was clinically tachycardic. Her pulse was so fast it would have been worrying had it been the patient’s. I have not forgotten this uninvited invasion of her heart. Although we now know that Galenic humours aren’t to be found in blood, and that the heart is not the seat of emotion, they remain physiological sources where our feelings and life stories can be read.

Sandeep Jauhar, a New York cardiologist, knows it’s possible to die of a broken heart. He describes how distress can cause our beating pump to change shape. Part-memoir, part-history of his medical specialty, Heart links the physical organ with the emotional one. Jauhar pairs engaging descriptions of how the heart works with tales of creativity and self-experimentation that enabled treatments for infarctions, arrhythmias and myopathies. It was the first I’d heard of the electrical engineer, Wilson Greatbatch, who blew his $2,000 savings to make the first implantable pacemaker. Today, that device metronomes one million hearts all over the world. These histories circulate around stories of Jauhar’s patients, his family and his own health fears. Aged 45, he finds himself staring at a CT scan that shows partial blockages in his coronary arteries. ‘I felt as if I were getting a glimpse of how I was probably going to die,’ he writes.

Jauhar doesn’t think fixing his, or anyone else’s, heart is a mere question of plumbing. It’s rare to hear a specialist say that ‘cardiology in its current form might have reached the limits of what it can do to prolong life’. The 1957 Framingham Study sought to predict a person’s risk of heart complications even before symptoms appeared. The researchers measured things that were easy to measure (like cholesterol and blood pressure), while choosing to dismiss ‘psychosomatic, constitutional, or sociological determinents’. In the 1950s, this passed as scientific rigour. Today, it sounds like wilful ignorance. Jauhar despairs that the American Heart Association still does not list emotional stress among its key modifiable risk factors for heart disease.

Rose George is also interested in the body’s physiological functions, and as a journalist, not a doctor, she has an even keener eye for their social and political qualities. She has written previously about the global waste and transit industries. In Nine Pints, she revisits these themes on the smaller square-footage of the human frame. Blood is a commodity. It’s the 13th most traded product in the world, and moe than 1,000 times more expensive than crude oil. But blood is no normal product: paying for it makes it less safe. A blood market that rewards sellers rather than donors attracts people at the highest risk of carrying blood-borne illness (saying that far the greatest risk of any transfusion is human error in mismatching the blood with the patient). Having a reliable donation system is critical. A unit of blood currently costs the NHS £124.46 — a steal. After Brexit, the price of a pint is sure to go up.

George’s nine chapters demonstrate that blood is a living tissue which defies our attempts to make it stand still. We meet fascinating characters like the haematologist Janet Vaughan, who set up London’s Emergency Blood Transfusion Service in 1939, with its fleet of repurposed ice cream vans delivering the red stuff around the capital. We are talked through the practice of applying leeches to help re-graft amputated ears. It’s a health and safety nightmare because each annelid worm is essentially ‘a needle that can walk’. On to South Africa, and the changing face of the Aids epidemic. In Nepal we learn about the practice of chapaudi, the social exclusion of girls on their periods. George’s tone deepens with authority and anger: prisoners have been extorted for their plasma; in the 1980s, British haemophiliacs received contaminated clotting factors; adverts from the feminine hygiene industry still depict menstrual flow with blue water. Beliefs around blood have always been a form of aspiration, as well as the basis for exclusion and shame.

Nine Pints and Heart close with excited visions for future innovation: artificial blood and artificial organs. But both authors warn against too much medicine. What are we willing to try to live that bit longer? A company called Ambrosia runs a trans-fusion service using plasma from young people to ‘superboost’ old veins (if you cough up $8,000 per bag). More than half of all transfusions in the US already have no clinical indication. Ever more sophisticated implantable defibrillators will flog the heart in its final pitiful beats. Rather than requesting yet another intervention, Jauhar reminds us of the comfort that may be found in seeing the heart as a ‘safety valve that can facilitate a quick and humane end’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

![[Credit: Julie Edwards]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Mark_Kermode.jpg?w=620)

![[Getty]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DNA_pic.jpg?w=620)

![An English oak in a misty meadow at dawn [Getty]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/oak_tree.jpg?w=620)

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in