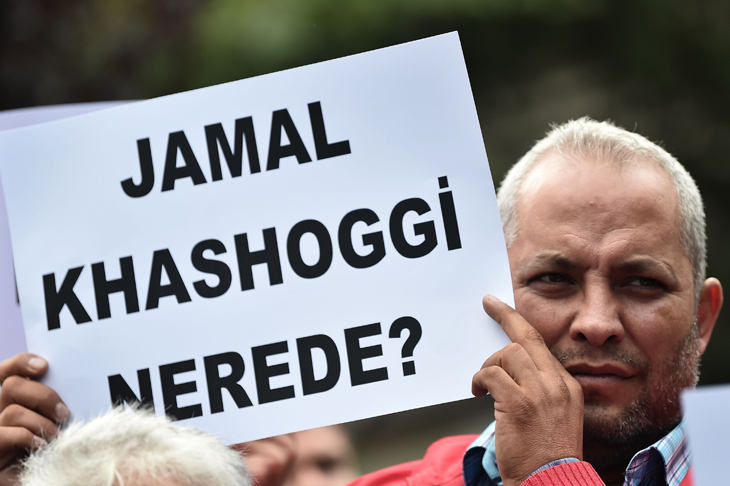

It wasn’t until the mid-1980’s that the party-pooping Ulema shut down Saudi Arabia’s cinemas. So there’s a good chance that Jamal Khashoggi, born in 1958, saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarves at his local flea-pit around the same time I did. And if his parents bought the soundtrack album, as mine did, young Jamal may even have sung along to it, as I still sometimes do. At time of writing the Turkish police have still not found Mr Khashoggi’s dismembered corpse, but if they ever do, perhaps ‘Some Day my Prince will Come’ should be played at his funeral as a warning to other disobliging expat journos.

The Khashoggi affair has certainly kyboshed any lingering hopes that Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman might be a catalyst for meaningful change in the birthplace of Wahhabism. It’s true that since MBS came to power the cinema ban has been lifted and Saudi women are now allowed to drive. But when it comes to stuff like free speech, religious tolerance and human rights the needle has only shifted perceptibly in a downward direction. According to anti-death penalty lobbyists Reprieve, public executions in the kingdom have more than doubled in the past year, while members of its LGBT community are still flogged and tortured on a daily basis. And as far as Saudi foreign policy goes, the continuing relentless bombardment of its Yemeni neighbours – as much as whatever just happened in Turkey – suggests that the affable young man made so welcome in Downing Street and Pennsylvania Avenue in recent months has no more respect for human life and no less ruthless an instinct for self-preservation than any of his predecessors.

But if it’s business as usual in Riyadh, what a difference 18 years can make in Washington. Or rather, what a difference two administration changes can make. Now that the White House has accepted that Mr Khashoggi did cark it soon after entering the embassy, and that his death wasn’t the result of a spat with the doorman, President Trump has promised to take ‘very serious’ action if the Crown Prince or any of his people are found to have been involved. However empty this promise may turn out to be, and however token any subsequent sanctions are, Trump’s mere acknowledgment that Riyadh might have a case to answer is a dramatic departure from the script followed by both his predecessors when confronted by even more compelling evidence of exported Saudi skulduggery.

The differences are in the detail. In this latest incident a small group of Saudi nationals are known to have travelled to a foreign country to kill someone, and at time of writing we don’t know if this ‘hit-squad’ was sponsored by anyone in the Saudi government. 18 years ago, another small group of Saudis travelled abroad with equally murderous intent. They also succeeded, but instead of despatching one aberrant countryman in the privacy of their embassy they murdered over 2,000 innocent foreigners in a very public arena. Yet despite the fact that 15 of the 19 who flew the planes into the Twin Towers and the Pentagon were identified almost immediately as Saudi nationals, and despite the fact that two of them were subsequently found to have been financed in the US by the Saudi ambassador’s wife, nobody in the Bush administration ever suggested that Saudi Arabia might have a least as much to do with 9/11 as either of the two countries America subsequently invaded. And despite Obama’s pre-election promise to the bereaved families that he would make public the 32 redacted pages of the official 9/11 government report which detailed these Saudi connections, he never actually did.

It would be nice to think that President Trump is more willing to talk tough with Saudi Arabia than were either of his predecessors for the same reason he was more willing to talk tough with Angela Merkel and Kim Jong-un. That unconstrained as The Donald is by traditional diplomatic protocols, he just calls and tweets things as he sees them, regardless of the damage that might do. A more realistic explanation, I fear, is that since embracing fracking so enthusiastically, America’s dependence on Saudi oil has been at an historic low.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in