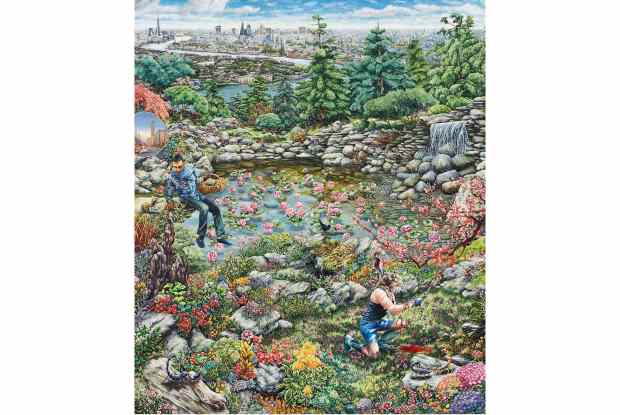

‘About suffering’, W.H. Auden memorably argued in his poem ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, the old masters ‘were never wrong’. Great and terrible events — martyrdoms and nativities — took place amid everyday life, while other people were eating, opening a window or ‘just walking dully along’. As an example, Auden took ‘The Fall of Icarus’ by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. As it happens, Auden himself was wrong there, because the work he cited is no long thought to be by the painter after all.

This picture is not, therefore, included in the exhibition Bruegel at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. However, the fact that Icarus has now been consigned to the vague penumbra of ‘after’ and ‘circle of’ is a detail. On the essential point, Auden was absolutely correct. You see it time after time in this marvellous array of paintings. Time and again, Bruegel hides away the scene that you might have imagined was the whole point of his picture.

Thus, in his ‘Conversion of Saul’ (1567) the future St Paul is not front and central, the hero of the story, as he is in, say, Raphael’s or Michelangelo’s version of the event. He has been thrown to the earth by a heavenly apparition — but in the middle distance. It takes a moment before you discover him: a little sprawling figure surrounded by a whole army column of horsemen and lancers marching over a high mountain pass with a steep drop down to the plains below.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum has 12 paintings by Bruegel in its own collection — out of a total of only about 40 — to which in the exhibition are added numerous loans including prints and drawings. The result does not quite reassemble every remaining work, but it is as close as we are ever going to get, and is most unlikely to happen again remotely soon, if ever.

The exhibition reunites four of the six panels of the ‘Seasons’ that Bruegel painted in 1565. ‘Hunters in the Snow’, the midwinter scene, is one of the best-known images in art history; ‘Return of the Herd’ and ‘Gloomy Day’, devoted to late autumn and the dismal period of February and March respectively, are not far behind in celebrity. These are currently joined by the ‘Haymakers’ from Prague. (The high summer scene, ‘Harvesters’, is unfortunately too fragile to travel from New York, while the sixth panel, dealing with spring, disappeared very early on.) Even so, to see these four great paintings lined up on a wall is reason enough to get on a plane to Austria. And there’s a huge amount more.

Bruegel’s career was relatively brief — his major paintings all date from the decade between the late 1550s and 1569, when he died, and his surviving oils are correspondingly few. The effect of showing most of his masterpieces together is overwhelmingly rich. That’s because there’s so much in each.

In ‘Christ carrying the Cross’ (1564) the Saviour is almost lost in the crowd packed with onlookers, travellers, soldiers, fights, children. The rolling, verdant landscape is punctuated with the sinister wheels, erected on poles, on which criminals were left to die, their limbs broken (there are many more of these in Bruegel’s ‘Triumph of Death’ from Madrid, the most terrifying image, to my mind, in the history of art).

At the Kunsthistorisches Museum, ‘Christ carrying the Cross’ is displayed without its frame in a glass case, so you can get really close — and also see how thin it is: a film of paint on an oak panel only millimetres thick. On such wafers of wood Bruegel could conjure an entire world.

It would be easy to spend hours in front of such a picture: part nightmare of cruelty and death, part glorious panorama of rural life and countryside. Bruegel liked to pack together such ingredients — horror, beauty, comedy, mortality. His exact meaning in a picture, if there was one, is often elusive, but his art still gives a compelling impression of truth. It is perhaps no coincidence that Shakespeare was his (much younger) contemporary.

He is an artist about whom little is known for sure. We are not certain where he came from nor when he was born or even how his name was spelt (like Shakespeare’s it varied). Probably he was only in his early forties when he died in 1569. Bruegel was mobile, living in Antwerp, then moving to Brussels; at one point he travelled to Italy over the Alps, which, to judge from his landscapes with their mountains and distant prospects, made a huge impression. Later he painted a view of Naples which — only firmly attributed recently — is one of the surprises of the show.

Among Bruegel’s friends was a renowned geographer, Abraham Ortelius, who still ‘weeping’ composed a eulogy to the painter. Ortelius had a keen appreciation of his dead friend’s art. He owned Bruegel’s beautiful monochrome ‘Death of the Virgin’, a virtuoso demonstration of how light, space and volume could be created with just varying shades of grey.

In Bruegel’s work, Ortelius noted, ‘there is always more matter for reflection than there is painting’. In other words, the pictures are packed with meaning — even if it is often hard to discern what that meaning is. Scholars are still debating the significance of such enigmatic images as his mysterious drawing of beekeepers, masked like Renaissance spacemen. But the uncertainty does not matter. Somehow just by looking you feel Bruegel’s sense of how things are: funny, tragic, lovely, terrible.

Ortelius also claimed that Bruegel ‘painted many things that cannot be painted’. You can see what he meant when you compare ‘Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap’ (1565) with the later reworking of the composition, perhaps by Bruegel’s son, Pieter the Younger, one of the best of some 150 imitations of this especially popular scene.

The original, however, has a subtlety and nuance that isn’t there in the copy beside it. In Bruegel’s own version, there is space between the bare branches of the wintry trees, and a chilly, slightly hazy air.

Bruegel’s observation of the world around and the people in it must have been not only searching but also unceasing. In the excellent accompanying book, published in England by Thames & Hudson, it is suggested that he must have made many thousands of drawings, of which only a few dozen survive.

He saw things nobody had noticed, or at least painted, before. ‘The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow’ (1567) depicts a blizzard of fat flakes fluttering in the murky air and half obscuring a village filled with soldiers. ‘The Holy Family’ is hidden away — in a way Auden would have approved of — half-visible, in a dark corner. This is perhaps the first painting to represent a snowstorm; I can’t think of another one until Turner’s.

This wonderful retrospective has only one drawback: there is too much to take in. I spent about four hours in the galleries. But it wasn’t nearly enough.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in