Los Angeles/Seattle

US stocks briefly rallied after the midterm results as markets looked favourably on a divided Congress and the possibility of cooperation between Donald Trump and House Democrats. The Fed kept interest rates on hold until next month, while remarking on strong growth and a continuing fall in unemployment. That, in a nutshell, is the economic news as I land at Los Angeles — but a more vivid update is delivered, as ever, by the talkative cab driver who takes me into the city.

He’s from Mexico, and his story is a cameo of the vigour with which Americans build their own prosperity as best they can. He didn’t vote because he’s still awaiting citizenship after many years in the US, where he owns a house that’s rising in value and his son serves in the military. But he would have voted Republican because ‘Democrats give people welfare, make them lazy’. And, in a vivid expression of the ‘nativist’ tendency of settled immigrants to turn against those who try to follow, he thinks Trump is right to rage against the caravan of would-be immigrants from Honduras: ‘They want to come here but they don’t want to work.’

Lunching with a friend in Malibu the following day, I watch sunlight dancing on the ocean and a sense of West Coast wellbeing surrounds us. Yet that same evening there’s a multiple shooting in a bar at nearby Thousand Oaks, and 48 hours later my friend’s home is reduced to ash by rampaging out-of-season wildfires. America’s prosperity also has dark undertones and omens.

Richer and poorer

I carried that thought to a conference in Seattle, the handsome waterside city that is the home of Amazon, Boeing, Microsoft and Starbucks — but also, we swiftly learn, of many homeless people for whom the prosperity generated by these global corporations has made local housing unaffordable.

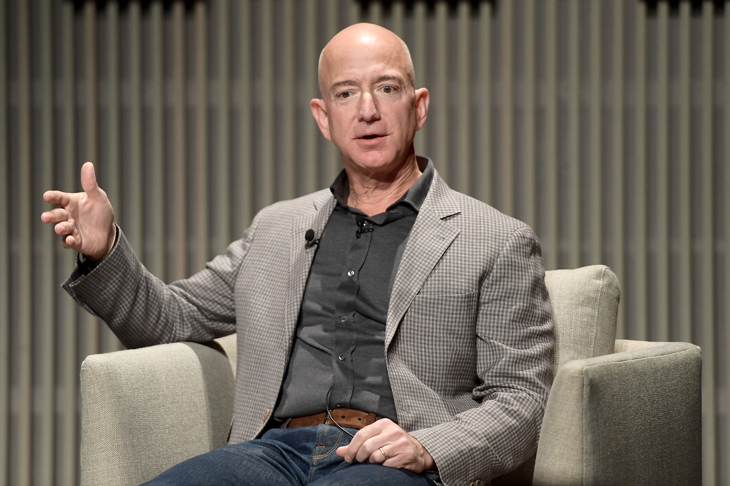

Here, too, are the world’s richest men, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, both now at the stage when they are judged more by their philanthropy than their potential to accumulate even more wealth. Indeed I wrote last year about the rather meaningless debate as to which is actually the richer, both having passed the $90 billion mark. I concluded that although Bezos’s Amazon shares may be worth more than Gates’s stake in Microsoft, Gates is ahead by a distance in the practical sense that he has found more fruitful ways to spend his money and, in doing so, causes people to admire him. Contrasting visits to the Gates Foundation and Amazon’s corporate HQ confirmed my view.

The Foundation — the world’s best endowed charity — offered a warm welcome. I learned that it is not only trying to eliminate polio and malaria from the planet, but also investing $400 million in bringing cleaner toilets to the half of the world’s population that lacks safe sanitation; that’s as down-to-earth as billionaire benevolence gets and will do vastly more good than, for example, Jeff Bezos’s space travel project, Blue Origin. But Bezos and his company do street-level philanthropy too: we hear much about Mary’s Place, a hostel that accommodates 60 homeless families within Amazon’s city-centre office campus, and that Bezos is planning to expand.

Jeff’s Balls

I had wanted to quiz Jeff personally about how many other families around the world might be helped if Amazon paid the same taxes as the domestic competitors it crushes, rather than employing towers full of tax magicians to minimise the company’s global bill. However, my hopes were disappointed. He was not to be found in the jungle–planted geodesic domes known locally as ‘Jeff’s Balls’ that provide a showpiece workspace for some of his staff. But at least I gained a rather startling glimpse of the secretive and defensive corporate culture he has fathered on his technologically awesome business.

I was still hoping to ask someone my tax question at the next tour stop. This was Amazon Go, a supermarket without checkouts where sensors identify you, track anything picked off the shelf and charge you for it through your phone. But no sooner had I downloaded the app than all hell broke loose. Whether or not it was the ceiling cameras that identified me, my visitor badge was abruptly unclipped and I was ushered off the premises. It turned out I’d been blacklisted by Amazon’s PR people and should never have been allowed on the tour. Bizarre, you might think, for a retailer whose top ‘leadership principle’ is ‘customer obsession’ — but good to know The Spectator strikes fear into one of the world’s mightiest corporations.

West Coast fads

I observe two new consumer crazes here. The first is rented electric scooters: Ford just paid $80 million for a two-year-old San Francisco start-up called Spin which operates scooter fleets in a dozen US cities. Two other scooter ventures, Bird and Lime, ‘each hit the $1 billion valuation mark faster than any other US start-ups in history’, says the Wall Street Journal. But if this fad reaches the UK I predict trouble: even American urbanites who rarely walk anywhere find it tiresome to have earphone-clad riders weaving along sidewalks and dumping scooters randomly at the end of the ride, which is how the business model seems to work. We British are a nation of pedestrians, and the scooter peril could be our next great irritation.

The other craze is sous vide: slow vacuum-pack cooking in water at controlled — and unusually low — temperatures. First I overhear two learned UCLA professors discussing it over dinner, then I find myself visiting ChefSteps, a Seattle start-up co-founded by Chris Young — Heston Blumenthal’s former sidekick at The Fat Duck — who has perfected a digital water heater called Joule that is, I gather, the iPhone of the sous vide scene. Young’s entrepreneurial zest is infectious and Joule is my hot (but never too hot) suggestion for the keen cook’s Christmas present.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in