‘I want big things to do and vast spaces,’ Edward Burne-Jones wrote to his wife Georgiana in the 1870s. ‘And for common people to see them and say, “Oh! — only Oh!”’ That, however, was only the first part of my own reaction to the exhibition at Tate Britain of Burne-Jones’s works. Perhaps I’ve got a blind spot when it comes to B-J, but time and again I found myself thinking, ‘Oh no!’

Nonetheless, this comprehensive display and the accompanying catalogue give plenty of clues as to where he went wrong. Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833–98) followed an extremely unusual career path. He was the son of a struggling framer and gilder from Birmingham named Jones (he added ‘Burne’ much later to avoid ‘annihilation’ among the horde of Joneses). A clever lad, he went from King Edward’s School to Oxford, where he met his lifelong friend William Morris.

Burne-Jones did not go to art school, nor initially did he show much talent for drawing. In her catalogue essay Elizabeth Prettejohn writes approvingly that ‘in his intellectual habits’ he was more like ‘a conceptual artist of today’. In other words, he was an intellectual, driven by ideas, rather than a practitioner of the brush, fascinated, as the late Gillian Ayres put it, by ‘what paint can do’. But even those concepts of his were remarkably nebulous.

Burne-Jones wanted his pictures to be ‘a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was’. The location of this he described as ‘a land that no one can define or remember, only desire’. These are pictures of nowhere, which may be why figures don’t pay much attention to what’s going on.

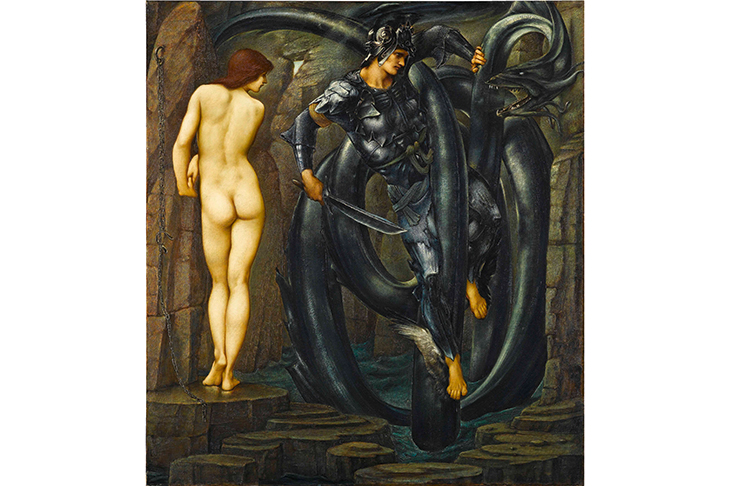

Sometimes Burne-Jones depicted striking events such as the slaying of dragons. But there is a listlessness even in the way the paint is applied. The result often suggests one of those awkward social gatherings at which no one can think of anything to say.

Andromeda, in ‘The Doom Fulfilled’ (1888), is taking only the faintest interest in the proceedings, despite the fact that she is stark naked and chained to a rock. At her side Perseus, equally impassive, is slashing away at the coils of the gigantic sea serpent. A speech bubble above Andromeda’s head might read: ‘What is he up to now?’

This air of polite puzzlement pervades ‘The Morning of the Resurrection’ (1886) in which the risen Christ has sidled in a little diffidently on the right, Mary Magdalene looks thoroughly disconcerted and the two angels stare resolutely ahead, determined to pretend that nothing embarrassing has taken place.

Although he was brought up an evangelical Christian, and was drawn early on to the high church Tractarian movement, Burne-Jones’s religious views were, it seems, characteristically hazy. ‘I love Christmas carol Christianity,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t do without medieval Christianity.’ This was, obviously, a different matter from believing in it.

His predicament — attempting to produce spiritual paintings despite a loss of faith — was one he shared with many 19th-century painters (Van Gogh, Gauguin and Delacroix among them). The problem with Burne-Jones, as far as I’m concerned, is the absence of gusto with which he went about it. Though that perhaps helps to explain why Gladstone made him a baronet.

In common with his epoch, Burne-Jones took his idea of what art was from Renaissance Italy. There is plenty of evidence of how assiduously he studied Titian and Michelangelo —the Sistine ceiling is the source of his muscular male nudes. But he drained all the life and energy from these models. The real Renaissance was far earthier and more full-blooded.

‘The Golden Stairs’ (1880) obviously owes a lot to Botticelli. But its emotional tone suggests an old-fashioned girls’ school. It depicts a troop of identical young women decorously stepping down the staircase. A few of them are exchanging a word or two. But most simply stare into space, the blankness of their features slightly tinged with dismay. Almost all Burne-Jones’s portraits — including an elderly, balding man — have the same face as these maidens. Apparently, he had no interest in human individuality.

Rossetti noted that Burne-Jones was ‘one of the nicest young fellows in — Dreamland’. And it is true that he was good at unconsciousness. ‘The Legend of Briar Rose’ series (1885–90) from Buscot Park includes some of his most successful efforts. This may be connected with the fact that virtually every single figure in them is asleep — a state that perfectly suited B-J’s expressive range.

To be fair, he was good at this kind of high-toned décor. His tapestries and stained glass are more fun to look at than his paintings because those media supply more oomph than his politely unobtrusive brush-strokes. But the fundamental trouble is that Burne-Jones’s dreamland is not interestingly weird, like surrealism, but boringly well-mannered. Wanting people to say ‘Oh!’, it turns out, isn’t enough of an ambition.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in