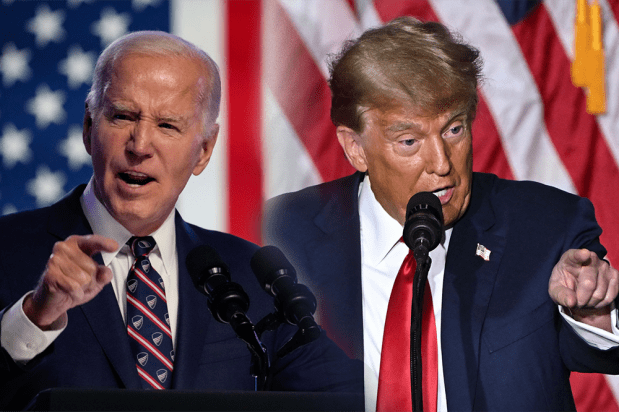

Donald Trump can, at the very least, claim to have killed off political apathy. Americans this week voted in greater numbers than in any such elections of the past half-century — but it does not follow that this is an encouraging development.

The midterm results were a blow for Trump, but not much of a blow. American politics is developing along the lines with which we are familiar: a cultural war, where voters are enthused not so much by what candidates have to say but because of tribal hatred of the opposition.

President Trump has proved an even more incendiary figure than candidate Trump: he has not stopped campaigning or using Twitter to set the news agenda. His enemies have not stopped rising to his bait. He has an extraordinary fiscal record to boast about: the US economy is booming and polls show that voters believe his reforms are to thank for this. But he has said very little about his economic success. At one stage during the midterm campaign, he tore up a speech on tax cuts saying he found the topic ‘boring’. Instead, he spoke about immigration, thinking this would encourage more outrage.

Trump avoided the suburban and metropolitan districts, which turned against him. He campaigned in rural seats, where turnout rose the most. Tactically, this made sense. Americans might not be very divided on Trump’s tax cuts, but they certainly are divided on treatment of illegal immigrants, which was a major theme of his campaign.

The splits we saw when Trump was elected in 2016, between graduates and school dropouts, the prosperous and the left-behind, have deepened further. This might have made for a foul public discourse, with the Republicans producing adverts that even Fox News refused to air, but these tactics halted what Democrats had hoped would be a ‘blue wave’.

Many in Britain will look across the Atlantic fearful that our own politics are heading in the same direction. Brexit has engendered a similar tribalism, with two camps often speaking only to themselves. The tools of British democracy have become similarly crude, with Leave and Remain camps constantly trying to deny each other’s legitimacy rather than debating with each other. We are also importing some of America’s culture wars. Statue-pullers reside in our universities and the #MeToo movement continues to topple individuals. Witch hunts are now a normal feature of modern life. This week, the philosopher Roger Scruton has found himself the latest target of the mob.

In Britain though, there is an opportunity for a unifier. Someone who can avoid joining one side of a hysterical debate, and instead be the voice of calm. In America, Democrats are now copying Trump’s tactics and the two sides are happiest trusting in their own virtue and the moral delinquency of the other. We have not yet reached that point in Britain. A majority of voters here think the country is too divided and want a leader to bring the country together.

Theresa May once posed as such a leader. She was a reluctant Remain campaigner who accepted the referendum result and committed herself to an orderly Brexit. She came to the top job with the air of a leader who could carry her party and country with her. Yet she went on to use partisan language, calling an election because she felt the need to crush supposed saboteurs. Her reputation as a one-nation figure has been tarnished by her ‘citizens of nowhere’ rhetoric and the hangover from her days as home secretary. She is now indelibly associated with the Windrush scandal, the same ‘burning injustices’ she once railed against.

Her replacement, who may well appear next summer, will experience slightly calmer waters than May did after the referendum result. It will be a good time for a new start, for conciliation. The search is on for a figure in the Conservative party to take on the mantle, to find someone who can rise above the divisiveness of the referendum and its aftermath.

Labour does not seem remotely close to producing such a figure. On the contrary, the party is riven with even more disunity than the Tory party. It often seems more interested in internal purges, always looking for traitors rather than converts. Labour is stuck with a leader who has tribal appeal; party members admire Corbyn, while most Labour MPs regard him as extreme.

There is a vacancy for a leader who has the ability to find supporters in unlikely places and who wants to lead the country, not just a faction. It must be someone who can show warmth towards the struggling as well as earn the confidence of business, who has the imagination and courage to dump cherished policies that have failed and to learn from across the divide. It must be someone who thinks that those who disagree with them are wrong, but not necessarily bad.

They must also recognise that cultural issues are important. A great many people worry that minority opinions are seen as being not just incorrect but criminal. The response ought to be to urge common sense: to fight against the hysteria but in a calm way. To defend the common ground. The early Tony Blair was such a figure, as, briefly, was David Cameron. It is not clear, at present, where such a leader might come from. But America’s experience makes it clear what can happen in the absence of such leadership.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in