The 20th-century painter Balthus once suggested that the author of a book about him began with the words: ‘Balthus is an artist about whom we know nothing; now let’s look at his works.’Actually, there are many important figures about whom we know nothing, or at least very little. Giovanni Bellini is a case in point. Information we don’t have about him includes when he was born, and even whether he was the younger sibling of Gentile Bellini — as is usually assumed — or in fact his uncle.

The discovery a while ago of a Latin poem suggesting that in old age this artist of tranquilly thoughtful saints and Madonnas was in the habit of sleeping with a handsome young man has only complicated matters, though it does enliven his image. Consequently, a book such as Giovanni Bellini: The Art of Contemplation by Johannes Graves (Prestel, £95), contains a great deal of conjecture (and a considerable amount of cold water discreetly poured over other people’s theories). It can be warmly recommended, however, for the quality of its reproductions.

The converse is the case with Vincent van Gogh. We have an abundance of evidence about his life and work, much of it contained in his numerous letters. Consequently, there is an assumption that everything that can be found out, has been. But Martin Bailey, an indefatigable truffle-hound of Vangoghiana, has once more proved that supposition wrong with his latest book Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing, £25).

This deals with the year, from mid 1889 to May 1890, that the great painter spent in an asylum outside St-Rémy-de-Provence. Bailey has unearthed the admissions register for the hospital, revealing that the other patients were more disturbed — and disturbing — than Van Gogh disclosed to his brother. Bailey even arranged for Greenwich Observatory to project for him the nocturnal sky over southern France on June 14, 1889— the night before Van Gogh conceived his celebrated image of wildly swirling stars.

Retrospective meteorology rather than astronomy is the theme of Constable’s Skies by Mark Evans (V&A/Thames & Hudson, £14.95). This collates the artist’s cloud studies with the weather reports for the day they were done. On 21 September 1821, for example, the clouds cleared at sunset after earlier storms. And that is precisely what you see in Constable’s little picture, painted that evening on Hampstead Heath, looking towards Harrow. The effect is like a time machine.

Bellini also features in Paul Hills’s marvellous Veiled Presence: Body and Drapery from Giotto to Titian (Yale, £45). This offers not new evidence so much as a fresh angle of observation. Hills explores an overlooked phenomenon. A great deal of Renaissance (and not only Renaissance) art is concerned with the representation of cloth, furnishing fabric and all manner of ways of dressing. Even undressed Venuses are usually reclining on mounds of sheets and pillows. These were crucial accessories for the artist, who could, say, express anguish through fluttering folds, and dignity with sweeping robes. But it is easy to forget those eloquent textiles. This is a book which will open your eyes.

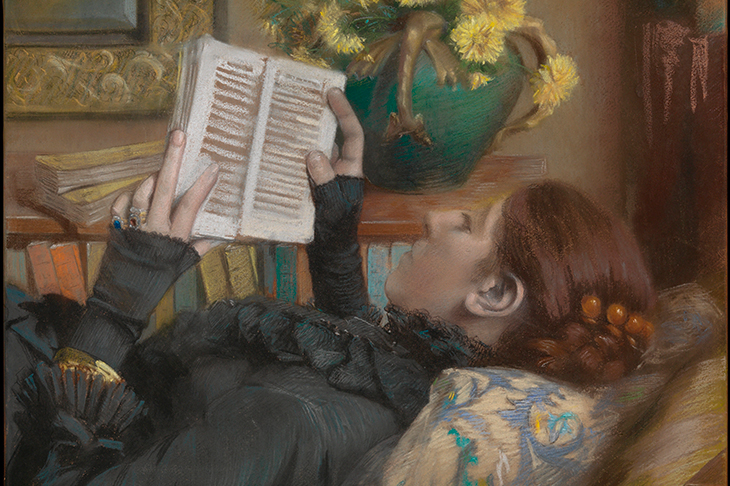

Another overlooked ingredient in art is the subject of Books Do Furnish a Painting by Jamie Camplin and Maria Ranuro (Thames & Hudson, £24.95). Personally, I have been told by more than one painter that reading during sittings is forbidden (apparently it makes the model less engaged). However, Camplin and Ranuro demonstrate that many artists, from Rembrandt to Cézanne, have not been so severe.

Books are prominent in many portraits — clasped in their subjects’ hands, lining the wall behind them or the desks to their side. They also pile up in still-life compositions, saints reflect on them, and allegorical figures brandish them. That’s as it should be. After all, civilised life is unthinkable without reading and books.

Standard texts, on the other hand, don’t necessarily contain everything important. Sometimes whole cultures fall through the cracks. Armenia was an important place in the development of Christian art, yet it tends to feature, if at all, as a provincial off-shoot of Byzantium. This is unjust, since the Armenians converted to Christianity in 301 AD, even before the Emperor Constantine saw the light. They maintained a lively, independent tradition in the arts for many centuries.

Armenia: Art, Religion and Trade in the Middle Ages edited by Helen Evans (Yale £50) is the lavish catalogue of a splendid exhibition held in New York’s Metropolitan Museum. It not only illustrates and describes manuscripts, carvings, metalwork and ceramics but also the churches and monasteries from which they came.

There are plenty of Byzantine walls and domes in The Photographs of Joan Leigh Fermor: Artist and Lover (Haus Publishing, £25). Most of these pictures were taken in Greece between 1945 and 1960, in the years before mass tourism. Hence the impression they give of quietness and emptiness, even in spots such as Mycenae which now pullulate with tour groups. John Craxton, the painter who (posthumously) contributes an introduction, recalled that arriving in Greece just after the war was like ‘striking oil’. It certainly looks enviably undisturbed in these photographs.

Joan’s spouse, Patrick Leigh Fermor, pops up discussing gluttony in On the Seven Deadly Sins, a lively anthology, both literary and visual, compiled by Kenneth Baker (Unicorn, £30). These days, criticism of some sins is considered offensive. The avaricious still gets a lot of stick (a picture of Philip Green appears in this chapter), so do the inappropriately lustful. But envy and rage are the life and soul of social media, while pride and vanity have been rebranded as self-esteem. Leigh Fermor’s observation that gluttony is ‘the only sin that turns us into monsters’ verges perilously on fat-shaming in 2018. This section, however, with its pictures of the unashamedly massive, might prove a useful corrective to overeating during the festive period.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

![The China-Russia East Route pipeline under construction in 2017. At 3,968 km in length, it is designed to carry 38 billion cubic metres of natural gas from Russia’s Far East to Shanghai. [Getty]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pipeline.jpg?w=620)

![The Earl of Southampton, to whom Shakespeare dedicated ‘The Rape of Lucrece’. [Getty]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/The_Earl_of_Southampton.jpg?w=620)

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in