There is very little art about modern poverty, because who wants to know? It is barely acknowledged, unless there is redemption, or salvation, as in A Christmas Carol. Those most suited to make it — those who are actually poor — are usually too busy doing something else, such as surviving.

So, it is remarkable to learn that Alexander Zeldin’s play LOVE, a success at the National Theatre in 2016, is now a film and will air this weekend on BBC2. The closest thing to it recently was Benefits Street, which was exploitative and, therefore, an instant hit.

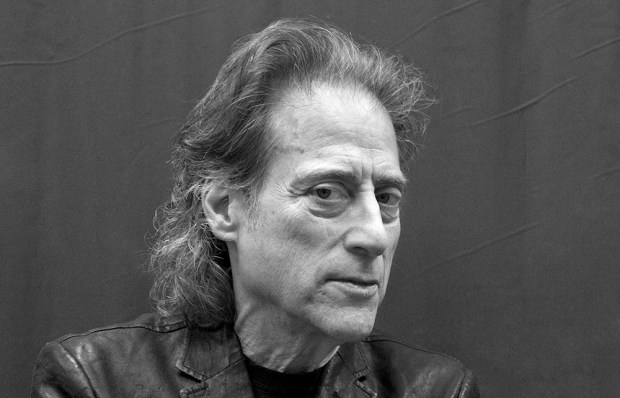

Zeldin is 33. He read French at Oxford University and is artist-in-residence at the National Theatre. His work is plain and understated. He listens, rather than writes, and there are no diatribes, just calm despair. His previous play, Beyond Caring, is about workers on zero-hours contracts in a sausage factory. Tiny losses aggregate: a coffee machine steals a pound; there are not enough wheels on a mop bucket; a washing-up glove is lost. The losses swell and threaten to overwhelm: a mother can’t see her child; a woman judged fit for work is nothing of the sort; they will be paid late. ‘But I can’t tell you what or how many hours you’re going to be working,’ the boss, an ordinary monster called Ian, tells them, ‘as responsiveness is part of the brief.’ Not being available at any time is posited as a moral defect and they wilt, effectively slaves. It is blacker even than LOVE, the second in this trilogy. The final play is about children in care.

LOVE is set in temporary housing in a west London suburb at Christmas. There is an elderly mother and her son, marvellously played by Anna Calder-Marshall and Nick Holder. She is ill, and he is mentally fragile; but the council won’t house them. There is a family with young children. He (Luke Clarke) has lost his job and she (Janet Etuk) is pregnant. They have been evicted from their home and sanctioned for non-attendance at a meeting at the Job Centre on the day of their eviction — despite having permission to be absent. He collects food from a food bank and pretends, to his children, that he has already eaten. ‘Food from a food bank — the supply — is a free good, and by definition there is an almost infinite demand for a free good,’ said Lord Freud, the Minister of State for Welfare Reform in 2013, which sums up the reason — the reasoning — for their plight. It is this denial that Zeldin seeks to conquer.

There is also a Sudanese refugee, crooning songs to her faraway baby down a telephone.

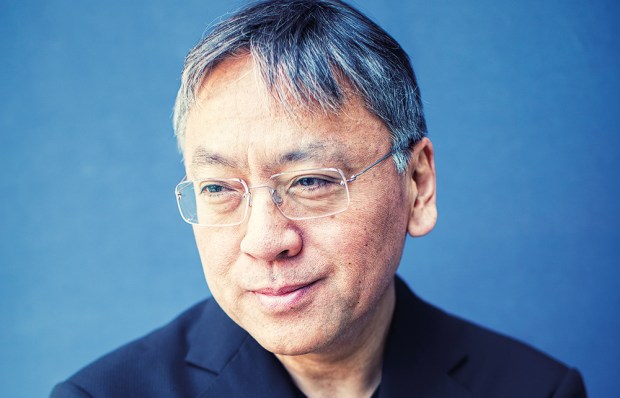

The press screening of LOVE is at the ICA on the Mall. It is a curious affair, principally because David Schwimmer, the very famous American TV actor — he played Ross in Friends — is here. He is the executive producer of LOVE and Zeldin’s friend. The cognitive dissonance of seeing Schwimmer at a screening of a film about poverty in Britain is entirely my problem, because he isn’t actually Ross from Friends. He just looks very like him. He co-founded the Lookingglass Theatre Company in Chicago in 1988 and adapts and directs plays on similar themes to Zeldin’s: Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, about working conditions in the meat-packing industry; Studs Terkel’s Race. His mother-in-law saw Beyond Caring and praised it. Schwimmer telephoned Zeldin’s agent, and invited him to adapt it for American audiences, which he did last year.

‘It’s really difficult,’ says Schwimmer, ‘to get these kinds of stories on the screen. It’s a story where there are no big fancy names in the cast and material that is challenging. We are all really grateful that the BBC exists because if you tried to make this film you could maybe make it independently, and try to raise money, but very few people are going to take that risk on a theatrical release with this kind of subject matter with a first-time film-maker.’

‘I was seeking to tell a family story,’ says Zeldin. ‘I was reading [John] Steinbeck’s novels — family epics in the context of the Depression, but they are really about family life.’ He found a Shelter report called ‘Christmas Families in B&Bs’. It appears every year. ‘This was a really detailed, that thick’ — he gestures, his thumbs an inch apart — ‘source of voices. Mums mainly, occasionally men, living with their kids in conditions described in our film.’ The children in LOVE respond differently. The boy skulks, his fingers in a cereal packet. The girl still believes her parents can save them.

They shot it in 15 days in a former school in Harrow during the heatwave. They worked 12-hour days. ‘Hustling the whole time,’ says Schwimmer, ‘relentless.’ He is serious and committed — ‘it’s the way I was raised’ — but he doesn’t want to talk about himself. He seems a man determined to give his good fortune away. Zeldin is more intense and detached. ‘I have to work from a place of something really touching me very deeply,’ he pauses, ‘and activating a kind of…’ he stops. ‘I just felt that the circumstances that were described, they allow us to tell a story about love, family love in a really strong way.’

Zeldin listens, as I said. He listens, among others, to Louise Walker, a mother of four who was housed in a B&B when her marriage ended. They were there for six months. Zeldin approached her and brought her to the rehearsal room ‘so they could understand what I went through. Alex allowed me to feel important’. He put her in the film. She explains that he is writing ‘for them [middle-class people] to see that this [their world] is not the world that everybody lives in’.

‘I love you,’ the man tells his sick mother before she leaves the hostel, possibly to die, after imagining she is in the sea in a thunderstorm, and free. The title — LOVE — is the only respite. Because it is all they have left: the ability to feel.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

![David Schwimmer has produced a new film of Alexander Zeldin’s play LOVE for the BBC. [Photo: Jose M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune/TNS via Getty Images]](https://www.spectator.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/8Declead.jpg?w=730&h=486&crop=1)

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in