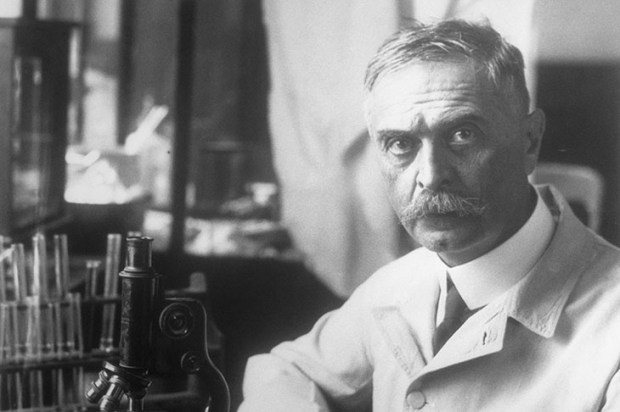

When H.H. Asquith, as prime minister, visited Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, during the first world war, he found a vast noisy factory churning out the most sophisticated means of destroying human life. The firm, Armstrong Whitworth, would, during that war, supply Britain with 12 armoured ships, 11 cruisers, 11 submarines, eight sloops, two floating power stations, 4,000 naval guns, 9,000 military guns, 14.5 million shells, 21 million shell cases, 100 tanks, three airships, over 1,000 aircraft, together with bombs, grenades and armour plate.

Asquith was accompanied by his daughter Violet, who sat beside the chairman of the company at dinner, a gigantic figure who her father described as having a ‘rather melancholy face and voice and the general air of a transplanted hidalgo’. They fell to discussing books, and she said to the armaments boss: ‘There is one book you must read. I cannot tell you why because its quality is indescribable — it is called The Nebuly Coat.’ ‘I wrote it’, he said. His name was John Meade Falkner.

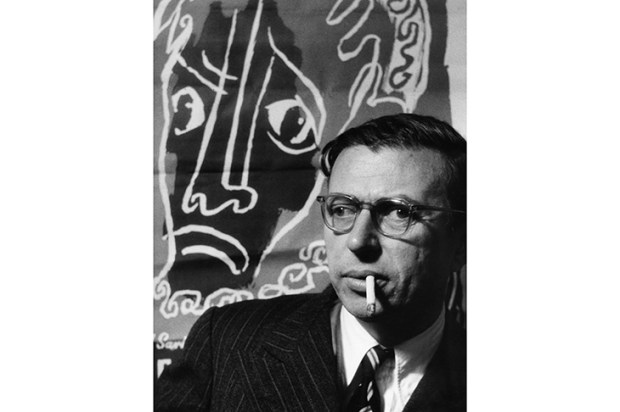

Falkner remains a mystery man, and in his wonderful book John Meade Falkner: Abnormal Romantic, Richard Davenport-Hines has stylishly allowed him to remain a mystery. He was the child of a Dorset parson who went up to Oxford (Hertford College), got himself a bad degree and, unwilling to follow in his father’s footsteps, drifted into the inevitable teaching. A friend who was a housemaster at Eton, Henry Luxmoore, recommended Falkner as tutor to cram the son of Sir Andrew Noble, the operational head of Armstrong Whitworth. What Davenport-Hines describes so well is the almost Widmerpudlian pushiness with which Falkner became Noble’s protégé, working his way up the firm’s hierarchy and ruthlessly undermining the ambitions of his rivals.

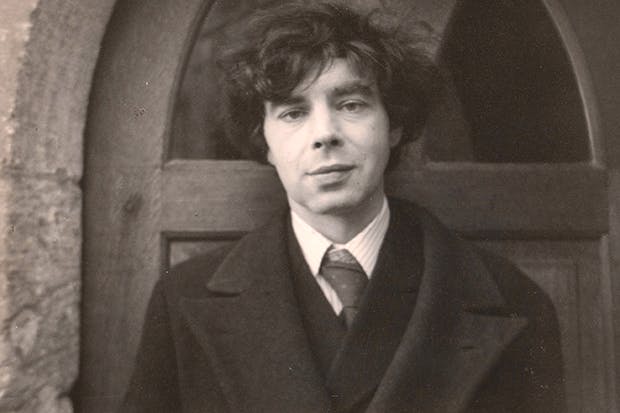

There was, however, another Falkner. As soon as he was established at the Newcastle firm, he took to living in Durham, travelling to work each day by train. In Durham, he lived the life of an antiquary, becoming the cathedral’s honorary librarian. His favourite evening of the month was the 15th, when the full Psalm 78 was sung by the cathedral choir.

The bishop, Hensley Henson, asked him why he never received Holy Communion, and he replied with a ‘confession of a vague, almost pantheistic sacramentalism’. During the war he liked to stay at the Beverley Arms Hotel and spend the morning sitting at the back of the minster, one of his favourite buildings in England. ‘In all Europe there is no more perfect harmony in architecture than here in Beverley Minster,’ he wrote, ‘and I pay tribute to the power of God and the inspiration of the workmen of bygone centuries.’

In his spare time he rambled and cycled in Oxfordshire and Berkshire, and produced the Handbook for Travellers in Oxfordshire, published by Murray in their series of guides to English counties. He was accompanied on these journeys by friends such as Skipper Lynham, who later taught Betjeman at the Dragon. Other travels — abroad — took him to South America and the Balkans, where he sold arms to unstable governments and tipped them off about the weapon capacity of their enemies and rivals.

Falkner was a good versifier, very nearly a poet, and certainly more interesting than the overrated Housman. His poem ‘The Last Church’, in which he imagines the very last time a church is used for worship before Christianity becomes extinct, is unforgettably tragic. After reading it, one begins to absorb that agonisingly nostalgic ‘feel’ which animates the great novels — Moonfleet, The Lost Stradivarius and, greatest of the three, The Nebuly Coat. There is no book like it, and one returns to it again and again.

Davenport-Hines brilliantly quotes Edward Mendelson (in quite another context) to explain Falkner’s mindset and his unique appeal: ‘To resist living in one’s own time, to attempt to live in an imaginary past, is human in the same way that being neurotic is human.’ The England of medieval churches and market towns, so beloved by Falkner, was wrecked by the social upheavals after the first world war which he, as a businessman, had done so much to promote. That is the hammer-blow horrible truth, the tragedy of Falkner’s divided self, which Davenport-Hines leaves us to work out for ourselves.

The book is printed in a limited edition for the Roxburghe Club, and is as handsome as you would expect. Falkner’s coat of arms, with its appropriate motto, Respice Finem, adorns the frontispiece

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in