We increasingly accept the collision between life and art. Whether we’re puzzling over the real identity of Elena Ferrante, choosing our own adventure in Bandersnatch, or boycotting the latest Polanski film, we’re buying into culture that’s more mirror than window.

But wasn’t it ever thus? It’s a case Barbara Strozzi would certainly argue. The most-published Italian composer of her age, a musician whose work could stand alongside Cavalli, Rossi, even Monteverdi, was caught throughout her career in the double-bind of biography. You have only to look at her famous portrait — gazing insolently out at the viewer, breast bared — to see the erotics of performance at work. But whether Strozzi merely accepted the inevitable inferences of her male audience or actively fostered them, building the only brand possible for a female artist at this time, is unclear.

What is beyond question, though, is her talent. Spilling out of the neat, miniature forms — songs, madrigals — that were permitted her, it’s a raging, passionate thing that begs for the scope of the opera stage. Where else could Kings Place’s Venus Unwrapped — a year-long festival celebrating a thousand years of female composers across 95 concerts — better begin than here?

Christian Curnyn and the Orchestra and Choir of the Age of Enlightenment were joined by soprano Mary Bevan for a concert whose handful of Strozzi songs and madrigals teased just a glimpse of this repertoire. There was much to savour in the naked sensuality of the ‘Canto di bella bocca’ — a duet brooding obsessively and indecently on a beautiful mouth — and the glistening flirtation of the trio for upper voices, ‘Le tre Gratie a Venere’. But there’s a depth to the solo songs that these more public madrigals lack, a sense of confessional intimacy that may be an illusion (Strozzi’s texts are never her own) but that speaks with seeming truth. What a shame we heard so few here.

Bevan gave us despair, in the keening wail that is the extraordinary ‘Lagrime mie’, and was carried along on the merry-go-round of unrequited love, churning relentlessly in the ground-bass of ‘E pazzo il mio core’ — the only singer among these polite early music voices to dare something ugly. If Strozzi’s life teaches us anything it’s that this was a woman who wasn’t afraid of a little dirt — musical or otherwise.

But where Strozzi was forced to elide life and art, for director Stefan Herheim it’s a choice, a persistent creative experiment. We saw it in 2008 in his Bayreuth Parisfal and again in his La Cenerentola for Lyon, and now it’s Tchaikovsky’s turn to become the troubled hero of his own Queen of Spades.

In the Royal Opera’s new production (already seen in Amsterdam) Herheim takes a gothic tale about human greed and turns it into an autobiographical exegesis. Tchaikovsky’s embattled homosexuality becomes the key to a production about dual (and duelling) selves and the conflict between private desire and public behaviour. The entire action plays out in the composer’s drawing room and his dying, cholera-inflamed imagination.

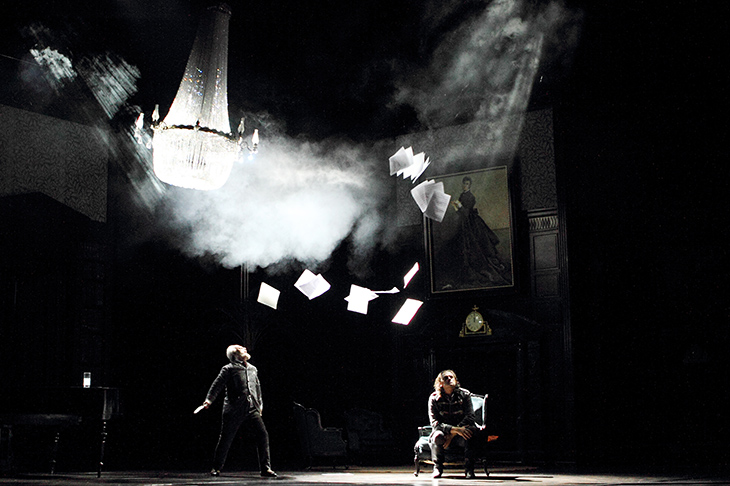

Herheim transforms the minor figure of the upstanding Prince Yelesky into the composer himself, caught in an elaborate performance of heterosexual duty, while secretly yearning for the destructive honesty and instinctive action of anti-hero Gherman. ‘Writing’ the opera in real time (which mostly involves a lot of florid air-conducting and flinging of manuscript pages) he seems to cast around for a self that fits, trying on every character for size — now the ardent, assertive Paulina, now the embittered old Countess.

As ever with Herheim, it’s an interesting idea, meticulously researched and referenced, but unnecessarily overcomplicated. Despite Philipp Fürhofer’s handsome and often ingenious designs, it never quite pivots from thesis to drama. A series of striking images — a chandelier swaying like a giant thurible; a ballroom full of masked Tchaikovskys; a Magic Flute-inspired pastorale — doesn’t quite add up to an emotional trajectory, and certainly doesn’t replace the all-but-discarded plot.

It’s a concept not helped by the startlingly poor quality of the two leads. Anything less than a triumphant Spades cast is a tragedy, and this is a long way from triumph. Aleksandrs Antonenko hacks out his Gherman as though out of marble with a mallet, and there’s no answering softness from Eva-Maria Westbroek’s rather wayward Liza either.

There are consolations elsewhere. Felicity Palmer’s Countess — a role that may be her farewell to the stage — is transfixing, pianissimos spun with ease, while John Lundgren’s superb Tomsky and Vladimir Stoyanov’s Yeletsky (dispatching his famous aria with sweetness and simplicity) only remind us what we’re missing elsewhere. But despite these, some fine singing from both adult and children’s choruses and Antonio Pappano’s full-blooded direction, this might be one worth waiting to see in revival.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in