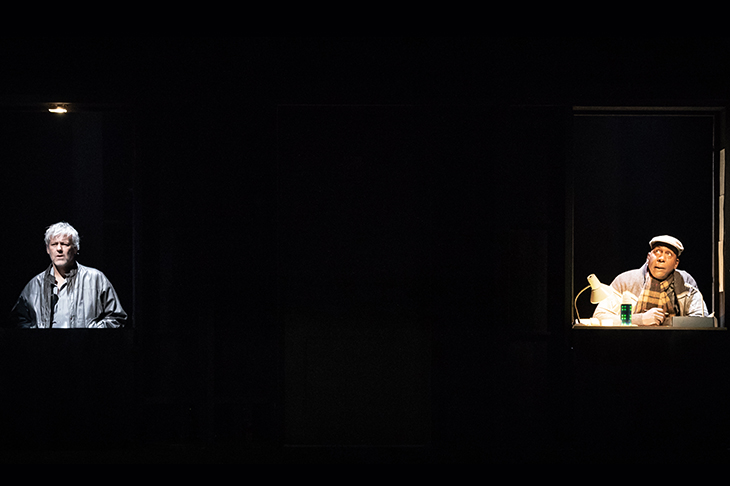

One masterpiece, one dud, and one interesting rediscovery. That’s Pinter Five. Victoria Station is a hilarious sketch which might have been turned into TV gold by the Pythons or the Two Ronnies. A radio controller needs a cabbie to collect a fare from Victoria Station, but the only driver available is a charming lunatic whose car is idling near a ‘dark park’. The cabbie already has a passenger on board, who may be a murder victim, and although he claims not to know Victoria Station he insists that he’s the best man for the job. This dotty piece of verbal slapstick feels a bit dated because cab firms no longer rely on radios. Yet the controller’s frustrations will strike a chord with anyone who has had to speak long-distance to an incompetent chatterbox who wants to help but has the IQ of a tree stump.

Family Voices is a radio play from 1981 about a mother trying to reconnect with her grown-up child. Pinter’s fraught relationship with his estranged son may have inspired this piece but it hasn’t developed into a satisfying drama. The voices from the radio play don’t translate well to the physical stage. The unnamed son has left home to join a gay commune in London where he mingles with various camp roustabouts whose behaviour he mimics. This feels like ancient history. Gay people these days can get married, adopt kids and receive knighthoods from the Palace. They’re so respectable they’re boring. And it’s astonishing to remember that they were once a glamorous and hunted minority who communicated in secret like spies or refugees. This weak, plotless drama flops badly.

The Room, from 1957, was the first play by Pinter ever staged. His tendency to portray women as either charladies or prostitutes is embodied in the character of Rose (Jane Horrocks), who seems to be a bit of both. She starts by delivering a ten-minute monologue while serving din-dins to her sulking husband (Rupert Graves). Enter Mr Kidd, a part-Jewish Irishman who may be Rose’s landlord or perhaps an imposter posing as her landlord. He drops hints that he has purchased Rose’s carnal favours in the past. A pair of brash yuppies barge in and suggest that Rose is about to be evicted. Finally, a drifter arrives and begs Rose to return to her former life, possibly in a brothel. All these uncertainties are intriguing rather than maddening, and the script ends with a satisfying act of clarity. One of the characters kicks another to death. What a pity Pinter so rarely finished his plays with a crunch moment like this rather than with a rambling and oblique monologue. Were he alive today he might have learned much from this debut.

The musical Caroline, or Change has a barmy title and a peculiarly threadbare storyline. We’re in a Louisiana suburb, in 1963, where the prosperous Gellmans are served by a laundry maid, Caroline, who works in the basement. The mother of Noah Gellman, eight years old, has died and he openly dislikes his kindly new stepmother, Rose. Instead he dotes on Caroline who allows him to take a sneaky puff of her daily cigarette. Rose tells Caroline that she can supplement her income by helping herself to spare coins from Noah’s trousers but Caroline resents having to grub for cash in the pockets of a schoolchild. ‘I ain’t no jackdaw rag-pick.’ Yet she needs the money for her growing family.

This curious tale is accompanied by an excellent set of hummable tunes and by smart visual effects. The washing machine comes alive in the shape of a singing goblin adorned with plastic bubbles. And Caroline’s radio set is incarnated by three swaying soul divas who wear sexy dresses with aerials sprouting from their costumes. All the characters are likeable apart from Caroline, a monumental sulk, who hates the Gellmans and disapproves of her teenage daughter’s euphoric love of life. This frozen hostility is brilliantly conjured by Sharon D. Clarke.

Then something happens. The ‘change’ of the title, which is initially a reference to Noah’s coins, alters its meaning and becomes a spiritual transformation that Caroline must complete in order to find redemption. In the second half she turns into a Christ-like figure who represents all earthly suffering. When she climbs a staircase from the basement to the upper floors of the house, her spirit appears to ascend from this veil of tears into paradise. The journey reveals why Caroline is portrayed as a truculent loser devoid of charm or cordiality. We are all Caroline. Her failings are the common lot of humanity and when she embraces forgiveness and peace the play becomes more than a drama, it becomes a religious experience. At the end, the crowd was on its feet. But many, spiritually, were on their knees as well.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in