Religion is an inescapable concept – everybody has a religion. Everybody has a basic set of assumptions about metaphysics, epistemology and ethics by which he lives, whether he consciously realises it or not. Everybody is religious. As the Supreme Court case Torcaso v Watkins acknowledged, even secular humanism is a religion (albeit, like Buddhism, non-theistic). But if being called religious is too objectionable, then we can at least agree that everybody has a Weltanschauung, or worldview, by which he lives his life.

So while many may suggest that we live in a post-Christian society, we still continue to live according to many of Christianity’s themes, the momentum generated from our Judeo-Christian heritage having not yet come to a complete standstill. While the garb has changed, the newly attired man still remains remarkably similar in appearance.

While God is dead, his shadow continues to be shown in caves. What may be referred to as the Aboriginal industry offers us an example of an ersatz, sublimated religion that our secular-humanist thought leaders practice, an attempt to cling to a system of values in the absence of a divine order.

Progressivism itself borrows its linear view of history from our Judeo-Christian heritage. Like Christianity, history is not cyclical but has a beginning, middle and end – it progresses in a certain direction, towards a certain end. It has a teleology. And like Christianity, the “middle” is the fulcrum on which history rests.

Whereas Christian history is viewed as being before Christ (BC) and after Christ (anno Domini – AD), progressives view the world as divided between before and after progressive enlightenment came into the world. Before this occurred, darkness and ignorance were upon the face of the deep, and prejudice moved upon the face of the waters.

But unto us (primarily since the ninety-sixties) progressivism was born, enlightenment was given, and the government ought to be upon its shoulders. With this light shone into the world, ignorance and prejudice would be progressively driven from the earth, until the last enemy, political incorrectness, is destroyed. This universal reign of peace and understanding will be forever and ever.

Progressives around the world take their cues primarily from the American historical experience, which is taken as being normative and is universalised, particularly American history over the last few decades. Prior to the sixties, for example, Jim Crow was not so much a phenomenon limited to the American South but rather a universal phenomenon with local equivalents to be found everywhere, whether in France, Brazil, Russia or New Zealand.

Fortuitously, Australia has a population that is suitably dark-skinned and suitably disadvantaged in measures of wellbeing as to offer a suitable approximation to the American historical experience. We too have our own people who, prior to the 1960s, were not even considered Australian citizens. Australian progressives, therefore, exercise the same elevated role as their American mentors in guiding society along the path of reconciliation and towards a shining city on a hill that radiates rainbow colours of harmony.

Aboriginals also offer to Australia’s progressives the sentimental figure of the “noble savage”, a free spirit not chained down to decadent civilisation, instead experiencing the ideal state of nature unsullied by fatal enlightenment. Australian progressives have as one of their most sacred missions the protection of this state of youthful innocence at all hazards.

The reality, however, is all too often a state of appalling dysfunction amongst Aboriginal communities that needs no recounting here. If a traditional Aboriginal lifestyle could genuinely be pulled off (assuming it would not be nasty, brutal and short), then I suppose I could live with that, given our pluralistic imperative to live and let live when harm is not done to another. The Maasai of Kenya offer an example of this, refusing the overtures of modern society to continue in their traditional lifestyle, but without the type of dysfunction associated with many Aboriginal communities attempting something claimed to be a traditional lifestyle.

So what should we want for the Aborigines? Should we seek to “Stanisise” them, turning them into various versions of Stan Grant, that is, people who successfully embrace and engage in Australia’s eudaimonia?

Stan Grant is Aboriginal, but only in conformance to hypodescent, to our one-drop rule, to the automatic identification with the subordinate Other; not in the sense of living traditionally as an Aborigine. The likes of Tony Abbott, when seeking to tackle Aboriginal disadvantage, would have someone like Stan Grant in mind as representing the end product to be desired: Aboriginal, but in name only, otherwise indistinguishable from the rest of us.

This, however, would rob progressives of their “noble savage” who needs to be protected from the corruption of the modern world. So the appalling states of dysfunction in Aboriginal communities must at all costs be allowed to continue unabated as if representing some idealised state of nature that remains innocent and unspoilt, a remnant of an Ede that existed in the time before the Fall.

But most of all, the abject state of Australia’s Other ultimately offers progressives the opportunity to practice the tenets of their faith, a bastardised version of the Judeo-Christian worldview. The mantras of “Apology” and “Reconciliation” are not so much an effort to remedy anything in practical terms as they are the religious utterances of penitents engaging in ritual self-flagellation for the expiation of their sins.

The sinners have fallen from grace because they have eaten the forbidden fruit of modernity, these gluttons gorging themselves on the fleshpots of the lucky country. They acknowledge their sins in “welcome to country” ceremonies, begging for forgiveness from those who suffer and die because of our arrival, who are the spotless and unblemished sacrificial offerings we make to our gods of greed and consumption. No recompense can be given, only an insufficient apology offered and an unworthy request for reconciliation be made.

So the correct way to approach Aboriginal disadvantage is not through a crude transactional process that seeks to measure progress according to some metrics, as the benighted Tony Abbotts of the world might offer. Such profane quantification is anathema! Stan Grant is an apostate!

No, the whole question is religious, an acknowledgement of the good news. This good news is that progressives have come into the world to set the captives free, to extract an apology and bring reconciliation through intersectionality. And the government shall be upon their shoulders, and they shall be called Wonderful, Enlightened, Everlasting Mandate, Party of Peace. Of their march through the institutions, there shall be no end.

This is the word of the progressives.

We are religious, and always will be. Man is inescapably a religious being. It is not a question of whether we are religious or not but rather what religion we subscribe to, whether we realise it or not.

The angst expressed about Aboriginal disadvantage is a morality play that admonishes and offers moral guidance. It is not so much about a practical problem to be fixed as it is a solemn observance to be made.

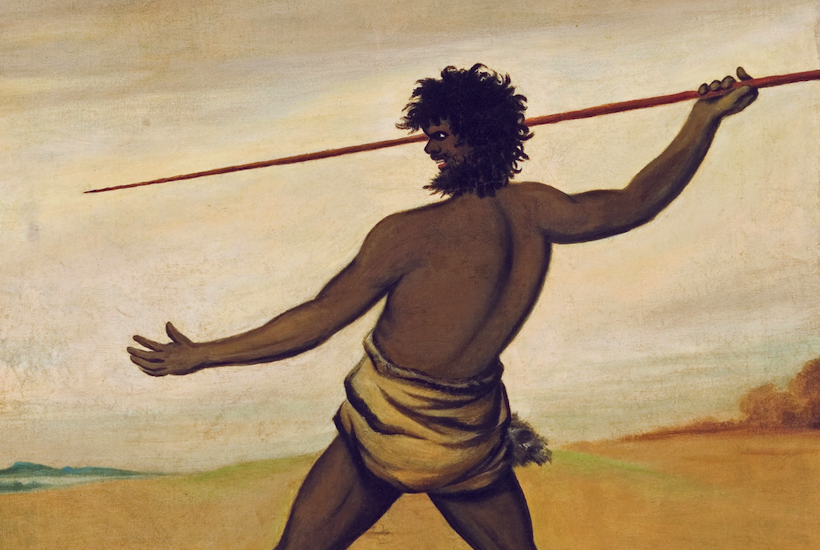

Illustration: Benjamin Duterrau; Timmy, a Tasmanian Aboriginal Throwing a Spear; Wikimedia Commons.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in