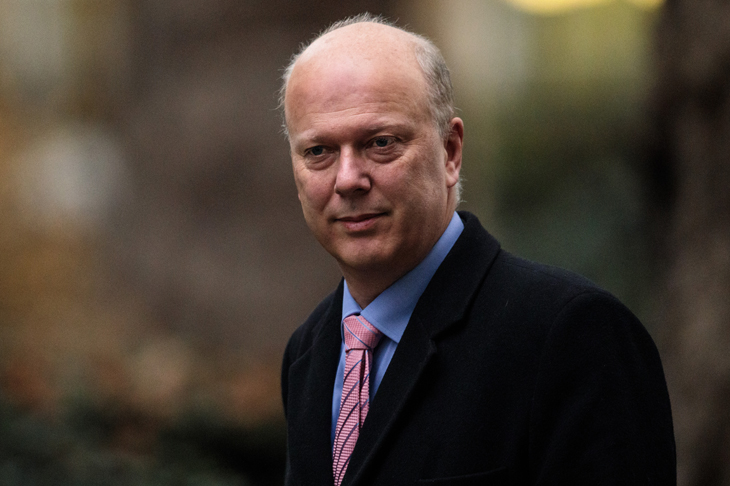

The Transport Secretary Chris Grayling may be quite right (not words one often reads) to warn that failure to deliver Brexit may end the culture of a broadly moderate politics in the UK and usher in an era of ugly extremism. The Roman republic was destroyed by a similar crisis.

In 137 bc, it became clear to Tiberius Gracchus — a grandson of the great Scipio Africanus who defeated Hannibal in 202 bc — that the men who had fought Rome’s overseas wars ‘are called masters of the world but have not a patch of earth to call their own’. So in 133 bc this aristocrat stood for office as a tribune of the plebs in order to bring about a land redistribution in favour of the poor. He did so for two reasons: first, the senate, populated by the rich who owned most of the land, would never agree to such a move; secondly, laws passed by the plebeian assembly were binding. Duly elected, he proposed a law that no family was allowed to own more than 325 acres of land (about 160 soccer pitches) plus an additional 150 acres for each son. Families who owned more should donate surplus land to the poor in 14-acre plots (about seven soccer pitches). His fellow tribune Octavius, leant on by the senate, vetoed this proposal, but Tiberius against all precedent had him forcibly removed ‘in the interests of the people’.

The law was passed, and a commission set up to implement the proposals and confiscate the land. The senate, naturally, under-resourced it. But Rome had recently been bequeathed the kingdom of Asia Minor (western Turkey), and Tiberius persuaded the people to vote to divert the ensuing windfall to the commission. This was bitterly disputed, so Tiberius decided to stand a second time as tribune (virtually unprecedented). A senate lynch-mob broke up the elections and Tiberius was murdered.

As Cicero later saw, this was the tipping point. For hundreds of years, senate and plebeian assemblies had worked together pretty well. Now a clear people’s mandate had been received which the upper classes used every trick in the book to reject — so whose side were you on? The result was a century of civil strife and bloodshed, and the end of the republic — which omen, MPs and Mr Bercow, may the gods avert.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in