A thought kept recurring as I read Toby Green’s fascinating and occasionally frustrating book on the development of West Africa from the 15th to 19th centuries: that the money in my pocket was just a piece of polypropylene. And what is that worth in the greater scheme of things?

The thought occured because money and its predecessor, barter goods, play a central role in the story Green has to tell in this monumental volume. The shells of the title are cowries, which for centuries were accepted as currency across the region. Cowries are not native to West Africa and had to be shipped from the Indian Ocean. But they worked as currency in the way polypropylene does: they had no absolute value but were accepted as currency because they were impossible to fake. West Africa had other commodities that could be used as currency and that appealed to Europeans. One was gold, the other humans.

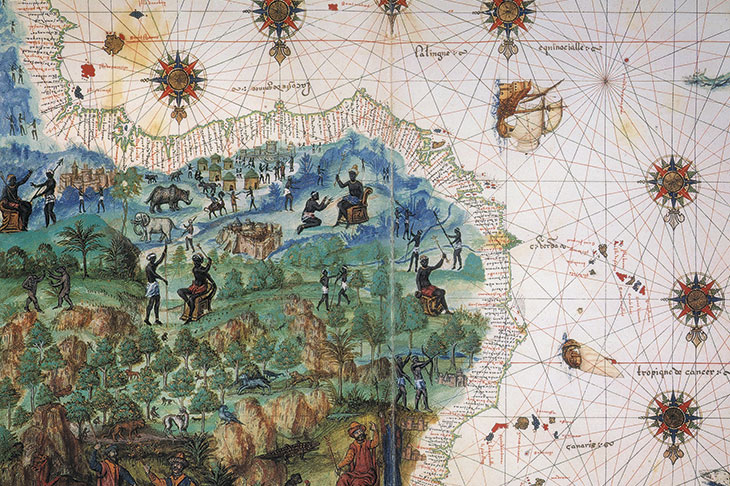

West Africa’s goldfields were already legendary in 1375, when a map of central Africa showed a king with a golden crown and sceptre, holding a pomegranate-sized nugget. This was Musa, the Mansa or King of Mali, who made one of the showiest entries ever on the pilgrimage to Mecca: his entire entourage was laden with gold and each of the 500 slaves who ran in front of him waved batons made from 2kg of gold.

It was recently estimated (by Time magazine) that Musa was the richest person who has ever lived, so he was clearly a significant figure. But that he is the most famous historical figure from West Africa until the 18th century or even later says more about how people in the West and elsewhere have written the region’s pre-colonial history than it does about Musa’s importance.

Left: View of Timbuktu, by the early 19th-century French explorer Auguste René Caillié. Right: Mansa Musa of Mali (c.1280–c.1337) with crown, sceptre and orb.

Left: View of Timbuktu, by the early 19th-century French explorer Auguste René Caillié. Right: Mansa Musa of Mali (c.1280–c.1337) with crown, sceptre and orb.

As Green explains, there were reasons for not telling that history, just as there were advantages in not recognising the legitimacy or even the existence of nations in West Africa, especially if you were Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, French or British and you wanted to trade or loot your way down the Atlantic coast. That this lack of historical record has not been corrected in our own time is depressing but not surprising. A Fistful of Shells attempts to rectify the situation by looking at economic, political, social and cultural development and, in the process, revealing the part these kingdoms played in the birth of our modern world.

Green previously worked as a journalist and a travel writer. Ten years ago he published a book about looking for mystics in West Africa, and since then he has been based at King’s College London, where he is now senior lecturer in lusophone African history and culture. This book combines both stages of his life, drawing on decades of first-hand experience, research in archives and discussions in seminar rooms.

All this makes for a rich and insightful work, but occasionally also an unhappy mix. Above all, do not judge this long, dense book by its introduction. Had I not been reviewing it, I might not have read past the beginning, which is often confusing, both in its statements and in its timeline, and I wish that Green had worked some magic on his text and that his editors had cleaned up some of its many repetitions. But I am glad I persevered, for there is much fascination to be had beyond the opening pages.

‘What,’ Green asks, ‘are the historical origins of African economic “underdevelopment”? How did African states change during this era?’ And perhaps more interesting, was it by chance that the second half of the 18th century was a time of revolution in Europe, the Americas and Africa? His responses draw on a wide range of sources, from published histories, new statistics and first-hand travel accounts to fiction, poetry, traditional songs and newly discovered oral histories, much of which

is revelatory.

What emerges is a radically different view of the region from the one that has been generally available. West Africa, according to Green, was both cosmopolitan in its outlook, culturally and politically sophisticated and in some ways globally connected long before Europeans arrived to ‘civilise the natives’. Among the most surprising revelations is the discovery that Europeans were rarely instigators of trade along the Atlantic coast, or even inland. What they did was develop existing markets and then often flood them with produce. In this way, they wrested control of trade away from Africans while at the same time destroying the value of gold dust, slaves, cowrie shells and other local commodities, particularly in their exchange value against European imports such as iron bars (another form of currency in the region) and bolts of cloth. The more that West African states traded with Europeans, the poorer most of them became. By the 19th century, some countries knew how to resist these developments, but others found a growing number of people turning to Islam as ‘a religion of struggle to resist inequality and the rising power of capitalism’, which sowed the seeds for the current jihadi unrest in the region.

Green concludes by pointing to the lack of history being taught in schools and universities in West Africa and elsewhere; if it is taught at all, it tends to focus on the slave trade. A Fistful of Shells shows that there was so much more, and of so much relevance when looking at the issues of our own time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in