All Is True is Kenneth Branagh’s biopic of Shakespeare’s last years and All Is Not Very True, apparently, which we could live with, but All Is Not Very Interesting either, which is harder to endure, particularly at the midway point when you feel a nice doze coming on. I don’t get it. I mean, if you are going to conjecture, why not conjecture inventively as they did, say, with Shakespeare in Love? If you’re going to soar freely into the realm of imaginings, soar high! But this is leaden, lifeless, sentimental and afflicted by too many sub-plots that just don’t go anywhere. Also, if this portrait of the greatest writer of any age were to be believed, he was a walking cliché. As well as a bit of a moron.

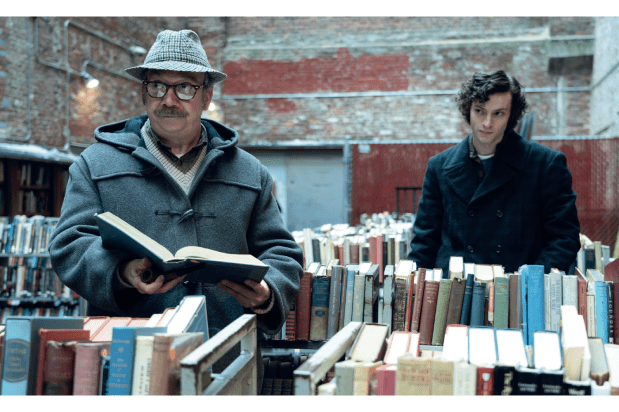

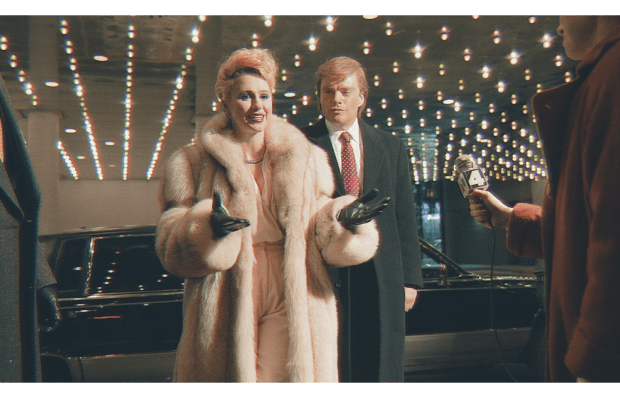

Written by Ben Elton, who also writes the Shakespeare TV sitcom Upstart Crow, this is directed by Branagh, who stars as the Bard, wearing a prosthetic nose that may be even more distracting than Margot Robbie’s in Mary Queen of Scots, which is saying something. It opens in 1613, with the Globe Theatre in London burning down after which, we are told, Shakespeare never wrote another play. (Untrue, apparently, but we’ll not worry about historical veracity from here on in, particularly as it’s the least of this film’s problems.)

He returns to his family in Stratford-upon-Avon. Here, he has his wife, Anne Hathaway, played by Judi Dench. Hathaway was eight years Shakespeare’s senior while Dench is 26 years Branagh’s senior. I am all for age-blind casting, but you can’t not notice, I’m afraid. Meanwhile, she serves as Chief Home Truth-Teller, repeatedly informing her husband how he has neglected his family down the years, which always brings tears to his eyes while a piano tinkles away on the soundtrack. The prosthetics don’t seem to allow Branagh much in the way of expression. Beyond tears in his eyes. While a piano tinkles.

Essentially, they have kid problems. One daughter, Susanna (Lydia Wilson), is married to a puritan bully and is having an affair while the other, Judith (Kathryn Wilder), is perpetually angry with her father. Shakespeare also had a son, Hamnet, who was Judith’s twin but he died when he was 11. Everyone refers to Shakespeare as a genius. Even Shakespeare refers to Shakespeare as a genius. But he can’t connect Judith’s anger to Hamnet’s death? I got there miles before him, I have to say, so who is the genius, really?

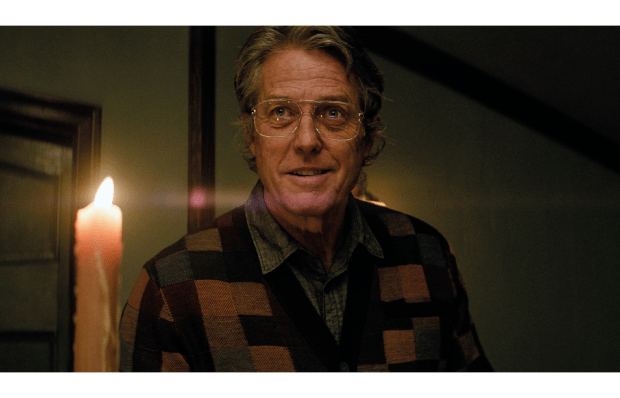

There are sub-plots aplenty, possibly because there doesn’t appear to be a main plot, but few stick around. For instance, you’d think Will would take on Susanna’s husband, given her husband wants to have all the theatres closed, but that just fizzles out. As for the script, it’s cliché after cliché. ‘Are you Shakespeare, the poet?’ he is asked by a kid. ‘You tell stories?’ ‘Used to,’ says Will. With tears in his eyes. The film does come to some sort of life when a bizarrely wigged Ian McKellen trucks up as the Earl of Southampton, who may, it is suggested, have once been Shakespeare’s lover. Their scene is touching. But as it has nothing to do with what has gone before and does not inform what is to come, it served no narrative purpose that I could fathom.

Certainly, you don’t come away with any sense of Shakespeare as a writer or any sense of him as a man, except as one beleaguered by soapy, second-rate plotting. I did fight my doze in the end, because I try to be professional, but if you can’t, no worries. You won’t miss much at all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Black Friday sale

Subscribe today and get 10 weeks of The Spectator Australia for just $1

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in