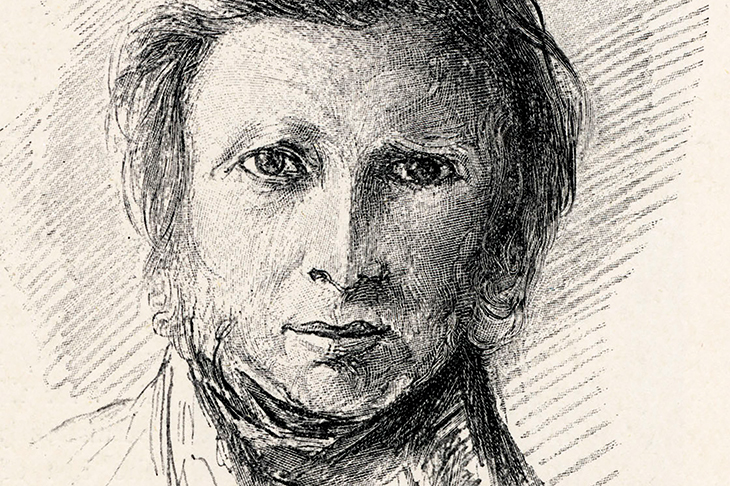

At the time of his death in 1900, John Ruskin was, according to Andrew Hill, ‘perhaps the most famous living Victorian apart from Queen Victoria herself’. He was a landmark — more or less literally. You could visit Brantwood, where he had his Lake District home in later life, and buy postcards of him. There were ‘Ruskin ceramics, Ruskin linen and lace products and Ruskin fireplaces’ available. In New Jersey, undismayed by the great man’s loathing of tobacco, there was a company that sold ‘John Ruskin’ premium cigars. Postmortem you could get Ruskin souvenir brassware or toasting forks and a scale model of the Ruskin monument near Keswick.

But that, Hill also says, was about the peak of his fame. Though everywhere these days you’ll find a street or a housing estate named after him, the 20th century was not kind to Ruskin’s reputation. He is vaguely known and little read now — and as Hill reports wanly on his very first page, most people to whom he mentioned the name Ruskin in the course of researching his book asked: ‘Wasn’t he the guy who…?’ Mostly those ellipses are filled with some variant on the phrase ‘fainted dead away when he found his wife had pubic hair’.

Master draughtsman, geologist, art historian, aesthetic theorist, architecture and handicrafts opinion-haver, prophet of ecological doom, author of jeremiads on economics and education, incurable Venice-botherer and madman: Ruskin had it all. But because he contained such multitudes, and wrote so much (there are nine million published words and his collected works run to 39 volumes; that’s before you get started on the letters), would-be Ruskinians find it hard to get a purchase on him. He found it, to be fair, hard to get a purchase on himself. As he once said: ‘I am never satisfied that I have handled a subject properly till I have contradicted myself at least three times.’

Yet it’s the thesis of this book — arranged thematically but draped on biographical bones — that we may not know Ruskin but we’re living, one way and another, in his world. His ideas about architectural and landscape conservation gave us the National Trust; his warnings of the environmental damage caused by industrial emissions anticipate modern green politics; his jeremiad against the ‘illth’ of unchecked capitalism in Unto This Last was influential in ideas about social democracy and the emergence of the 20th-century welfare state; as was his emphasis on the dignity of labour. He’s even claimed here for mindfulness, our growing interest in local provenance, and in so-called holistic approaches to living. Ruskin was a great join-the-dots man, and what he wrote of artistic composition — ‘the help of everything in the picture by everything else’ — also informed his view of the good life.

We might add, obviously, he was the great champion of Turner (who made him the executor of his will but didn’t leave him any paintings) and the Pre-Raphaelites (one of whom ran off with his wife) and a direct influence on William Morris — though Hill is careful to avoid lumping Ruskin’s Lakeland crafts in with the Arts and Crafts mob. And without Ruskin it’s hard to imagine that your Veneziana in Pizza Express would include a contribution to the campaign to stop Venice sinking into the lagoon. Hill, disappointingly, reports that there’s no discoverable evidence that Ruskin ever ate a pizza: if he did, he didn’t mention it.

The problem was, in part, that he was so various. Even the many expressly Ruskin-influenced institutions that Hill runs to ground here — from Oxford’s school of art to a Brick Lane furniture business and a designer handbag outlet — tend to pick and choose from the congenial parts of his contradictory legacy. And so does Hill: zipping back and forth and giving, in this shortish book, not so much a complete picture of the man as a series of illuminating glimpses, like one of his subject’s travelling sketchbooks.

Hill does, I should warn, crowbar in canting contemporary references to a degree that starts to look like mania. Ma and Pa Ruskin were ‘helicopter parents’, the young John would likely have ended up on the ‘gifted and talented register’, he’s considered in relation to Twitter (wouldn’t have liked the 280-character limit, we’re told), Snapchat, selfie-sticks, MailOnline and Celebrity Big Brother. The Pre-Raphs were ‘like the YBAs’, William Morris was an ‘early adopter’ and Ruskin was ‘what we would now call a thought leader’, who would, apparently, be in demand as a polarising TV host or a contributor to Question Time. Ruskin’s prose was the ‘high-definition film documentary of its day’, his lectures ‘a kind of Ruskinian PowerPoint’, his drawing curriculum ‘an analogue website’; and the crazily digressive outpourings of Fors Clavigera inspire Hill to think he would have been a ‘formidable blogger’. Might have been right about the last one, to be fair. Still, you grind your teeth.

Nevertheless, Hill doesn’t elide the many ways in which Ruskin wasn’t our contemporary. We learn that he hated trains, the Palace of Westminster, St Pancras, the Great Exhibition, bicycles and the colour black. He was a great feminist except when (most of the time) he wasn’t. He thought that the purpose of education was ‘no means of getting on in the world, but a means of staying pleasantly in your place there’. And Gladstone quoted him as saying: ‘I don’t think that prisons ought to be reformed, I don’t think slavery ought to have been abolished, and I don’t think war ought to be denounced.’ He publicly stuck up for a Governor of Jamaica who had killed a whole bunch of restive natives and flogged the rest with wire whips. Autres temps, autres moeurs.

The pubic hair thing, incidentally, is a canard. The record shows (somehow) that Ruskin was familiar with early Victorian porn, so the ‘incurable impotency’ that did for his marriage to Effie Gray wasn’t the result of a wedding-night surprise. The indication is that Ruskin was not asexual but tortured about sex and love — and his prodigious work-rate (plus, according to some Freudians, his sketches of suggestive-looking rock formations) likely testified to his sublimating all that.

In any case, the dissolution of his first marriage, as well as being publicly humiliating, left him with a terrible catch-22. When he was knocked flat by love in later life for the much younger Rose La Touche, marriage would have been tricky even if she’d accepted him (she didn’t, but she called him ‘St Crumpet’, which is nice): because any sign of consummation would potentially give the lie to the reason for the annulment of his first marriage and make him a bigamist. So, long story short, he had a nervous breakdown instead.

Hill’s is an eccentric and sometimes an irritating book — but its central emphasis upon Ruskin’s injunction that we labour to see clearly what’s actually in front of us, and to see the connections between those things, makes the case for its subject. It’s a glimpse into a vast and marvellous and now little travelled country, and for that alone it earns its place on the shelf.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in