MacDonald ‘Max’ Gill (1884–1947) is less well known than his notorious brother, Eric. But was he less of a designer, less of an artist?

The son of a Brighton clergyman, his career was built on a sequence of remarkable connections. The architect Halsey Ricardo, a descendant of the economist, was his tutor. While working for church builders Nicholson and Corlette, Gill very likely met Edwin Lutyens at the Art Workers’ Guild.

And for Nashdom, the neo-Georgian house Lutyens built in 1909 for Prince Dolgorouki at Burnham in Buckinghamshire, Gill drew an imaginative ‘Wind Map’. Somewhere between illustration and cartography, this was a pointer of what was soon to come from his pen and brush.

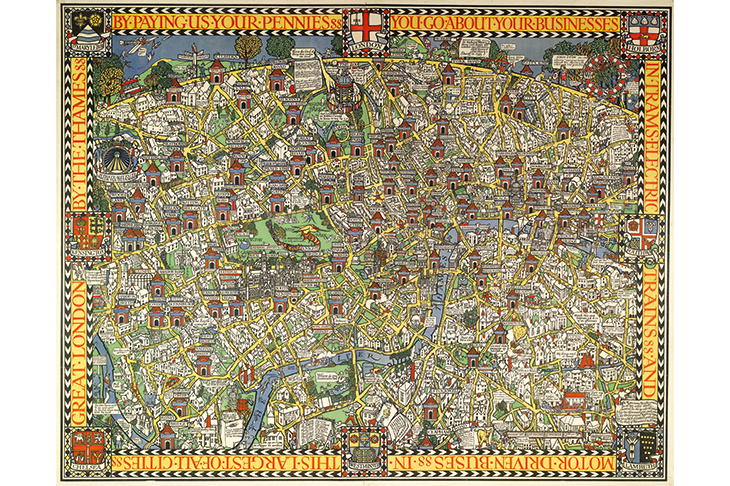

In 1913 Frank Pick, the publicity manager of the Underground Electric Railway Company of London, commissioned Gill to cheer up the Tube, then depressed by competition from the new motor buses. The result was Gill’s 1914 ‘Wonderground’, a fully mature realisation of the hybrid caricature maps he made his own. Displayed at every Tube station, it was the beginning of Pick’s consciousness-raising campaign, which positioned the future London Transport as a benign patron of the arts and an agent of good citizenship. ‘It makes the hoardings more popular than the trains,’ the Daily Sketch enthused.

(Pick would later become known as one of the great champions of modern design, a pioneer of what we now call ‘corporate identity’. His creation of London Transport bears comparison with Haussmann in Paris and Robert Moses in New York, although more imaginative than the former and more principled than the latter.)

‘Wonderground’ is seasoned whimsy. It is a late expression of merrie Imperial pleasantness, but it is also exceptional draughtsmanship: a synoptic marvel. Like Giambattista Nolli, whose Rome map of 1748 is the gold standard of imagined aerial views, Gill had perhaps never been in an aeroplane. But the London territory he surveyed was internal, not aerial: folkloric and a mite too cute for our taste. With perspective, ‘humourous’ has a deadly ring.

Significantly, it was also in 1913 that the Goertz company of Berlin developed the first viable camera for aerial photography. And very soon, aerial maps would acquire a more sinister purpose than jollying up passengers on the Bakerloo line.

Indeed, it is impossible to look at ‘Wonderground’ today and not feel haunted by the shadow of a future Gill did not see. Of that terrible year Thomas Hardy wrote: ‘Summer gave us sweets, but autumn wrought division.’ Within four years, Gill was designing the letterforms used on the 180,000 headstones of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

His brother Eric, writing in the Burlington Magazine, dismissed this effort as ‘feebly artistic’. Certainly, a more enduring typeface has been the one Pick commissioned from Edward Johnston, still in use on what is now TfL.

In 1922 Max Gill designed folding diagrammatic pocket maps of the Tube, but these were soon replaced by the more successful cartography of Frederick Stingemore who, in turn, ceded to Harry Beck’s timeless masterpiece of 1931.

Pick later managed posters for the Empire Marketing Board, while Gill created ‘Theatreland’ and other caricature maps for the International Tea Market Expansion Board (‘Tea Revives the World’, it says) and Post Office Wireless Stations, this last wittily tipping the British Isles on its axis to meet the demands of the landscape format.

A lesser artist than his brother? Certainly. Max Gill was drawing caricature maps with playful swash capitals and toytown details to nearly the end of his life.

Quite correctly, he wanted to tell us where to find the best rhododendrons near Woking, but Eric had higher purposes, if lower morals. Max never really moved on, while Eric, for all his incontinence in matters of love, was an altogether more austere and disciplined figure. Max, despite his 3-D effects, was one-dimensional while Eric professed the ambiguities of a great artist. Max’s type design was dignified, but inconsequential. His brother’s ‘Gill Sans’ remains in the canon.

But Wonderground Man has great charm and interest. Preceded by an exhibition at Snape Maltings in 2014, it is the second phase of a Max Gill revival that began with the discovery of a huge cache of his work in his wife’s nephew’s Sussex cottage 60 years after his death. It is a perfect miniature show in a perfect local museum, founded in 1985 and carefully refurbished by Adam Richards Architects in 2013.

The Gill brothers put Ditchling on the map. Pevsner found this South Downs village ‘disappointing’, but allowed that one house was ‘eminently picturesque in a watercolourist’s way’. And that faint praise must be the judgment on Max himself. Less notorious than Eric because less good. But wonderful nonetheless.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in