I once threw Tony Parker’s Lighthouse across the fo’c’sle of a ship at sea when I read that his characters were composites. Oral history should be historical, or it goes into the ocean. So it is a shame that I sometimes question Xinran’s authenticity in this account of the loves and lives of four generations of Chinese women. I question conversations recalled verbatim when they clearly weren’t recorded; and perfectly rendered speech when only notes were taken.

Is this too severe? Then it is appropriate, because severity is something you must get used to, though this is a book about the Chinese concept of ‘talk love’, defined as ‘the process of cultivating love or interacting on the basis of love’, possibly leading to marriage. Xinran was fortunate to find a family of women whose stories so illuminate this subject.

First we meet Red, born in 1920 to parents whose marriage was arranged but whose father charmed his new bride — who had bound ‘three-inch lily feet’ — by hanging trees with ribbons covered with poetry. That is not as startling as our introduction to Red herself, as an old woman whose husband on his deathbed insisted she have a virginity test, which revealed her a virgin. This seems to have been intended as a public testament of her noble suffering in a 61-year-long sexless marriage, though even Red doesn’t know why he demanded it. Instead of sex there was nothing more than a lot of ‘talk love’ — bedtime conversations between a wife and the husband who loved another woman.

This talking stuck their sexless marriage together, but so did concepts such as the ‘Three Obediences’: that a woman must ‘obey her father as a daughter, her husband as a wife, and her sons as a widow’. Transgression on her part would have been severely punished: a woman who took a lover was, by tradition, made to ride a wooden donkey, ‘a contraption made from wood, with a sharpened wooden stake attached that would be repeatedly forced into her vagina until she bled to death’.

Red’s siblings had better luck in love. Her sister Green (they were all nicknamed after a colour) was a young communist who fell for a man and for the party almost equally. She remained a true communist even after her schoolmates at a top Beijing girls’ school beat to death the deputy headmistress Bian Zhonguyn with wooden sticks studded with nails, making her the first victim of the Cultural Revolution.

Hers was a political marriage, but despite poor prospects one that seemed loving and solid. Green’s trip to her husband’s remote village also serves as a window into how history felt for people for whom it was the confusing, absurd present: ‘You could barely breathe for the chaos swirling around you.’ The narrowness of the women’s viewpoint — despite some being able to recite reams of political history, conversationally — gives you a powerful sense of this.

Their individual stories, then, convey the bewilderment of China’s wars and upheavals, its diktats and the distant decisions that meant life or death. This world seemed so chaotic that a brother was deafened by a bomb and ‘no one in the village could even say which army was responsible for the bombing’. When Green takes a ride inside a tank inside a train — she is confined for propriety’s sake — she listens to the young People’s Liberation Army soldiers chatting outside. They are PLA now, but that might change. ‘Doesn’t matter who you’re with,’ says one. ‘It’s still just carrying guns and eating.’

Later, Green’s daughter Crane is ‘rusticated’ to a village where the windows are ‘paper, not glass, of course’, and whose inhabitants must deal with constant change as best they can. In 1970 Mao wrote that the country must fight against xiãn yàn lùn (a priori philosophy). ‘But because that sounds a lot like xiãn yàn (brightly coloured), all of the villagers went home immediately and hid all their brightly coloured possessions in the cellar.’

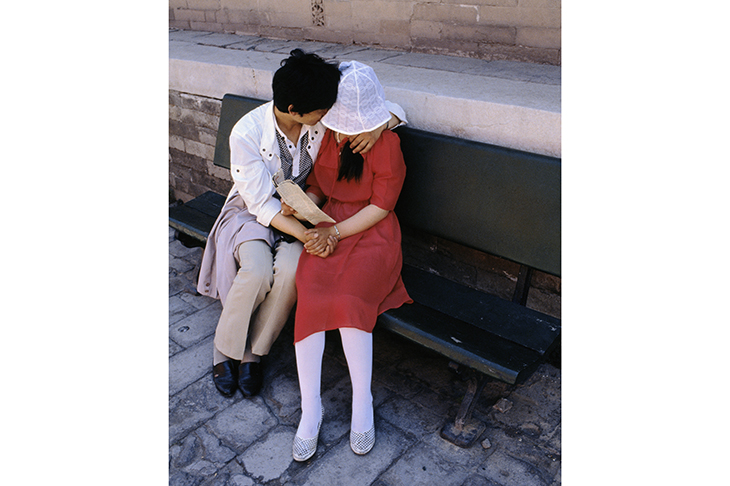

For these women, custom could be just as suffocating as politics. However laboriously and sometimes charmingly Xinran has her characters describe the components of rural custom (my notes read ‘festivals’ then ‘more festivals’), these villages are also places where tradition had young people who kissed in public executed, or women who dared pursue men punished according to ‘a heavenly principle’, and sometimes even sentenced to death.

Through this swirl of history, the women are the stable ones, putting down roots even when they are moved around, and when their beloved husbands and fathers are executed or flee to Hong Kong for safety. Their protests can be small: Orange, who goes mad from grief, calls her daughter Anti-America; another child is named — optimistically — No Scars.

Even the youngest, the ones who live in a modern, freer China (allegedly) recount experiences and attitudes that can sometimes seem as cold and alien as the terrifying violence of those wooden donkeys. Lili gets paid to pretend to be someone’s wife. Wuhen (No Scars) marries for duty and is dumped for reasons that now seem shocking: because she did not bear her husband a son. I warm to Wuhen, born into ‘a scarred family’, a gathering of women whose names are as colourful as the times they lived through, their stories of suffocation, strength and endurance both foreign and familiar.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in