In recent years, we’ve seen a resurgence of marketing campaigns targeted at children – Coles’ “Little Shop ”, Woolworths’ “Mr Squiggle”, and Commonwealth Bank’s Dollarmites. Each tries to get children to interact with the company in some way and to engage with its product or service. This is fascinating from a behavioural economics perspective because you can take one of two approaches to such campaigns: the boring take, and the interesting take.

The boring take is that these programs exploit parents’ affection for their children by having the children nag their parents to engage more with the company’s product. We’re familiar with this line – it used to be used to argue for restrictions on fast food advertising during children’s time on TV.

The interesting take is that these programs can be mutually beneficial for both parties. They can be good for parents, because they allow them to better integrate the experience of interacting with the company into the family lifestyle in a way that can be beneficial for children as well. And yes, they can be good for companies because while they’re probably relatively marginal in terms of profit, they help to better build the experience of interacting them into family lifestyles (to be sure from a young age) and build customer loyalty.

I know what you’re about to say. “Brendan, you’ve sold your soul to evil corporations who exploit children to boost their bottom line”. Well… sometimes I think a nice well-paid corporate job would be very pleasant. But that aside, let me walk you through the argument by introducing you to a unique perspective in behavioural economics that was developed by my doctoral advisor Associate Professor Peter Earl when he was himself a doctoral student at Cambridge.

Lifestyle economics, a sub-branch of behavioural economics, begins from the realisation put forward by the Nobel Prizewinner Herbert Simon, later Ron Heiner, and most recently Barry Schwartz that decision making is costly, and we don’t have the cognitive resources to be able to make heavily involved “rational” decisions.

We don’t go about our lives, for the most part, making fairly cognitively involved trade offs of costs and benefits to make conscious decisions about what to do. We literally can’t! We save that for the big stuff, for the really important decisions like choosing where to send our children to school or which city to live in.

Instead, we go about our lives acting out routines which we discover over time to, broadly speaking, “work” to get us what we need. It’s important to note that this is not irrational behaviour. We tend to call this “procedural” rationality in behavioural economics, because it involves developing a procedure which allows us to make fairly good decisions without crippling us.

If we collect all these routines into a totality, we get what we call your “lifestyle”. The set of routines you have which characterise how you go about your life.

Now when we interact with a company such as Coles or Commonwealth Bank, we typically will run one of these routines by visiting the store/branch or website to obtain the product or services we need. Simple enough.

But a lot of us also have children. And when we’re running that routine as part of everyday life, we would usually have to take time away from interacting with our children to take care of the business of everyday life. Or we might have to just ask them to be present and “behave” – sit quietly and let us go about that business.

What a campaign such as Little Shop or Dollarmites does is to allow us, in principle, to include our children and integrate them into the family routine, and in a manner which can actually be beneficial for them. They create an incentive for children to participate in the routine by creating an objective to be achieved by engaging with it which they find attractive. It allows us to “gamify” the routine somewhat and make it attractive for children to engage with.

For instance, when we visit the supermarket, an objective like getting a mini brand collectible with Coles Little Shop or Woolworths Mr Squiggle provides us with a way to give our children an attractive objective to help us with the shopping. That’s beneficial for children too, because they start to learn the routine of shopping which they will eventually have to action themselves.

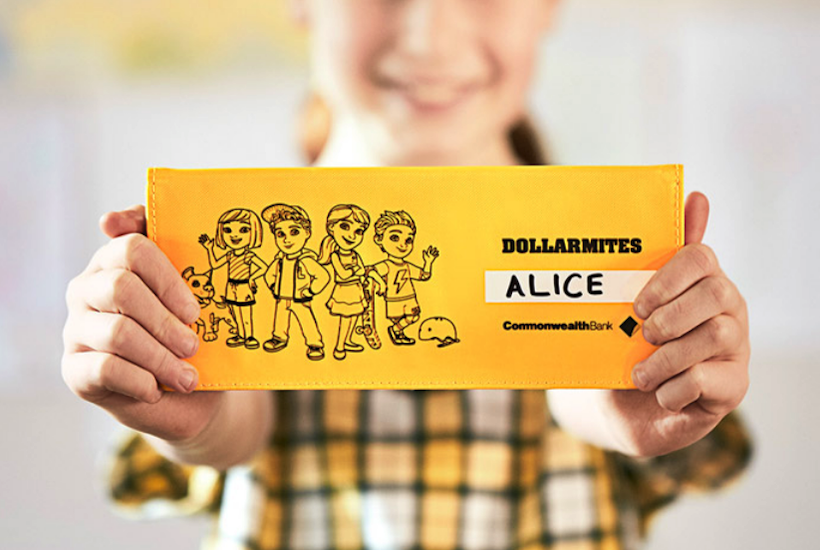

Similarly, when we’re doing our internet banking, a program like Dollarmite allows us to include our children to participate in the routine with us as well as on their own. We can set aside a time each day for the family to sit down and go through both Dad and Little Johnny’s finances and together work up to being able to play the game at the end. That’s, again beneficial for children, because they start to learn the routine of internet banking and money management which they will eventually have to action themselves.

Now if you’re an imaginative parent you can work out some way to do that anyway through gamification techniques. But it might take some expense like buying a treat or some such, and requires a bit of thought. What’s nice about such a campaign from a company is that it’s there, almost ready to use as a way to better integrate our children into the family lifestyle.

I for one find that almost rather poignant. Such programs as Little Shop or Dollarmite allow us to include children better into the experience of the family lifestyle and help them develop routines which they will have to execute themselves, where they would otherwise have to simply sit and let us get on with it. That’s good for us, good for our kids, and the company gets something from it as well as a degree of loyalty is developed while we build our lifestyle around interacting with it.

Some will look at the resurgence of marketing campaigns targeted at children and be horrified by companies trying to interact with them and get them to engage with the company’s product. I think this is boring. The more interesting perspective, which we obtain from behavioural lifestyle economics, is that such programs allow parents to better integrate children into the experience of interacting with the company to obtain its product or services into the family lifestyle.

They’re good for us, because they allow us to better include our children in actioning the various routines which comprise the family lifestyle. They’re good for our children, because they allow them to become better engaged with routines they will have to learn to action themselves. And they’re good for companies by helping them become built into the family routine and endowed with a certain loyalty.

Dr Brendan Markey-Towler is a behavioural economist and institutional cryptoeconomist affiliated with the RMIT Blockchain Innovation Hub.

Illustration: Commonwealth Bank.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in