One perhaps should not make too much out of remarks of one public official, no matter how senior – and yet, I have this nagging feeling that what he is expressing is a rather common view among those who consider themselves our betters:

It may be time to revisit Australia’s implied freedom of political communication, Queensland’s Anti-Discrimination Commissioner Scott McDougall says.

Queensland Senator Fraser Anning was roundly criticised after the Christchurch terrorist attack for his comments linking Muslim immigration with violence.

“The real cause of bloodshed on New Zealand streets today is the immigration program which allowed Muslim fanatics to migrate to New Zealand in the first place,” Senator Anning said in a press release.

Mr McDougall said there was a need to “dismantle the business model” of people benefiting either psychologically or commercially from the creation of fear, ignorance and hate.

“That means there has to be consequences,” he said.

“So the idea that anyone can go online and publish words that have real consequences for other people and not bear any responsibility for that, those days just have to end.

“Similarly, politicians need to be held to account for their use of language and whether they are licensing members of the community to engage in hate speech.”

Mr McDougall said it might be time to examine the implied freedom of political communication courts have found exists in the Australian constitution.

“It may be that the implied freedom of political communication needs to be revisited to draw a line around what freedoms society ought to tolerate,” he said.

“What is the price that we are prepared to accept for allowing unchecked free speech?”

McDougal went on talk about “what freedoms society ought to tolerate,” bringing back images of much-luvvied former human rights commissioner Gillian Triggs leaning through the window every morning with a notepad after she bewailed to the Bob Brown Foundation “Sadly, you can say what you like around the kitchen table at home.”

Please excuse my over-sensitivity to the question of what freedoms society – sorry, bureaucrats — ought to tolerate. I was born and lived my first decade and a half in a communist country, where the “society” decided not to tolerate quite a large range of speech and behaviour by the people.

Since that time I have been rather allergic to the idea of not being able to talk about some topics at all or not being able to say certain things about others. Freedom of expression is one reason why my post-communist life in Australia has been so enjoyable, and why blogging – without having to censor myself – has been such a big part of my life.

As someone who has lived without this freedom, it is not something I take for granted. I worry deeply about the attempts across the Western world to outlaw ideas and criminalise opinions some people don’t like. We already have defamation laws and laws against incitement to violence, about which there is a near universal consensus across the whole spectrum of political opinion, even if opinions might vary about a detail here and there.

But then we have the somewhat more contentious “vilification” laws, getting more and more contentious with every effort to expand their reach by the linguistic equivalent of a bracket creep.

Queensland’s Anti-Discrimination Commissioner wants to make people pay for “the creation of fear, ignorance and hate” – words have consequences and those who say them should be held responsible. But McDougall is not talking about someone saying, “Kill the Muslims”. That is already illegal. What he is talking about is someone saying for example “Let’s restrict immigration” because under the monumental bow he draws political debate can create a certain climate, in which in turn a deranged individual might decide to kill 50 people. That this is an idiotic and illogical rationale for public policy making becomes quickly apparent when contemplating some other examples that I doubt McDougall has considered.

For example, were an anti-Adani protester commit an act of industrial sabotage, which results in property damage or God forbid physical injuries, we should be stopping people from talking about climate change, since this in turn creates a climate of widespread fear where coal is vilified, and in turn, one person in a million might decide that democratic process is insufficient and matters have to be taken into own hands.

Remember, this is an example of a debate where no one is actually advocating killing coal miners. But what about instances where they do (though not miners)? The writings of Marx, for example, have clearly led to unprecedented bloodshed in the past. Should they be banned today? But why stop at “Capital”. Let’s prevent people from talking about income inequality, because that can contribute to the climate of hatred against the rich, and hey, someone might then decide to kill a banker.

There is also a very compelling case for banning the Koran – and, indeed, the Bible – because some of their violent and intolerant parts can (and indeed do, both historically and recently) inspire people to harm others.

It’s also clearly my classical liberal and natural law privilege speaking but I believe that freedom is something that belongs to all of us by virtue of being sentient human beings, and not some sort of a gift or a privilege to be granted under sufferance by the state – and conversely withdrawn from us when the state disapproves of how we exercise that freedom.

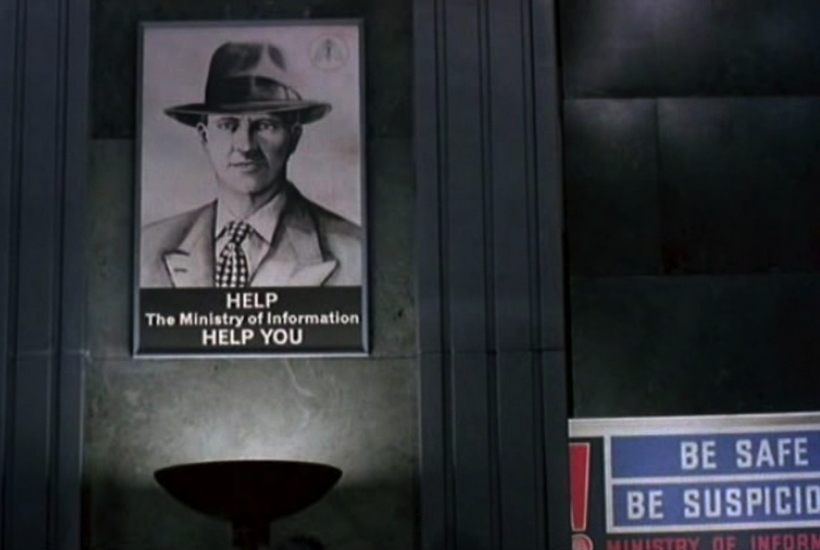

That’s why the idea that McDougall wants to decide (don’t be fooled by fancy disguises like “society”) the extent to which I can enjoy freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom of assembly, freedom of conscience, and many others is not just so offensive and outrageous – but fundamentally wrong, verging on evil.

Arthur Chrenkoff blogs at The Daily Chrenk, where this piece also appears.

Illustration: Embassy International Pictures/Brazil Productions/20th Century Fox/Universal Pictures.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in