There was a moment more than 20 years ago when Bankside Power Station was derelict but its transformation into Tate Modern had not yet begun. I remember thinking, on a visit to the site, how beautiful and impressive the huge rusting generators looked — like enormous real-life sculptures by Anthony Caro. Nothing that has since been exhibited in what came to be called the Turbine Hall has looked quite so strong.

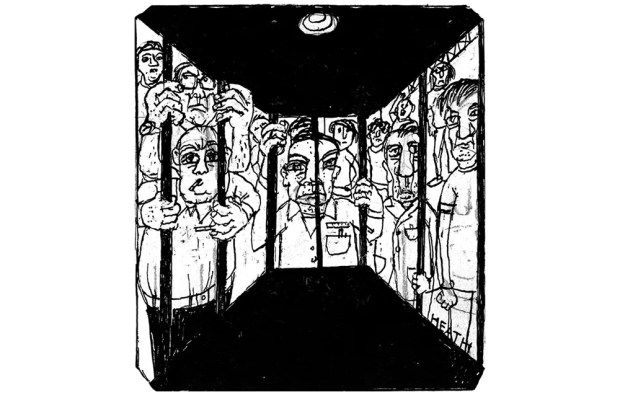

A quarter of a century later, the artist Mike Nelson has reversed the process — not at Tate Modern, but at Tate Britain where he has filled the Duveen Galleries with massive pieces of redundant machinery: cement mixers, engine blocks, metal filing cabinets, drill bits, racks, scaffolding and palettes of rough, functional wood. You enter through battered swing doors salvaged from a hospital. It all looks just as powerful — perhaps more so — than the pieces of sculpture that are usually displayed in these chilly, neoclassical spaces.

In a way, of course, this is a sculptural work — or at least an installation. Normally I think that this idiom, which consists of selecting and arranging real things, is limited in comparison with, say, carving or modelling. But that does not mean it cannot be done in a masterly fashion, and that’s what Nelson has achieved here.

His arrangement, entitled ‘The Asset Strippers’, looks ruggedly grand and is packed with complex implications. It consists of a mass of redundant equipment, fittings and fixtures accumulated by the artist from online auctions. In a very direct way, therefore, it’s about the end of an era: industries moving on and out of the country, a vast closing-down sale in which everything must go, entire eras of the past and ways of life included.

‘The Asset Strippers’ also manages to comment on art history. There was a phase — you could call it high modernism — during which many artists were in love with industry. You can see that in the paintings of Fernand Léger, among many others, and in the machine aesthetic of Bauhaus designers and architects. That’s why, as you wander around Nelson’s array of obsolete plant parts, it looks familiar — and in place — in the middle of Tate Britain.

‘The Asset Strippers’ is full of echoes of the futurists, constructivists and the heavy-metal sculptures of Caro, Richard Serra and John Chamberlain. In the centre of the galleries, surrounded by columns, is a set of hay rakes like so many metal Catherine wheels, carefully placed on timber trestles with a couple of trolleys lolling below in the manner of reclining river gods on a Greek pediment. At the same time, this looks very much like an arrangement of found objects by Marcel Duchamp — another great fan of engineering gadgets and contraptions — but on an epic scale

Mike Nelson himself is, I suspect, more a romantic than a modernist. ‘The Asset Strippers’ feels like an elegy for a world that is slipping away. As you walk around, it is hard not to think of globalisation, and the coming empire of artificial intelligence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in