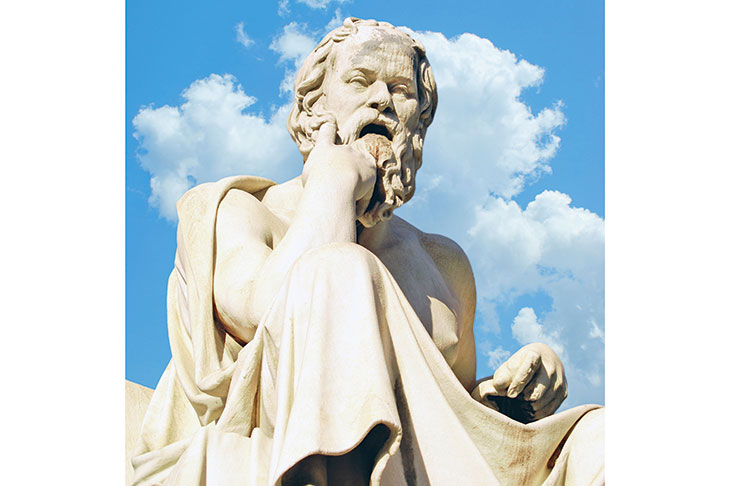

If western philosophy is no more than ‘footnotes to Plato’, so, arguably, is the myth of its founding hero, Socrates. While there is good evidence for certain aspects of Socrates’ life — his preoccupation with ethics, question-and-answer technique and his trial and death in 399 BC — most of it is shrouded in uncertainty. His only contemporary depictions are in a few satirical comedies by Aristophanes. It was Plato’s dialogues, composed in the half-century after Socrates’ death, which first presented their author’s beloved teacher as the ideal philosopher, tragic hero and sage; and although there were other writers of ‘Socratic dialogues’, it was Plato’s Socrates, above all, that bewitched philosophers, from Aristotle to Nietzsche. It is thanks to Plato that we have Socrates’ saying that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.

But how much can we ever know about the real Socrates? Armand D’Angour’s Socrates in Love is one of several recent attempts at an answer that are ‘not written for specialists’, but for a wider audience. The book is presented as a sort of tutorial, led by its author, a Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. A photograph in the foreword of an unidentified college window behind some daffodils evokes a serenely contemplative setting.

According to D’Angour, the problem with the Socrates of modern accounts is that his character lacks development, because it is restricted to his later years, when he was ‘physically unprepossessing’ and fully formed as a philosopher. This book aims to correct that picture. Assuming the role of ‘detective investigator’, D’Angour examines afresh the circumstantial evidence and a few less well-known sources to see what can be gleaned about Socrates’ early life, and, in particular, his loves. The result, he claims, is ‘surprising, fascinating and even shocking’.

D’Angour’s most ‘momentous’ claim concerns Aspasia, the seductively brilliant mistress, or possibly wife, of the great statesman Pericles, and one of only two women with a significant speaking role anywhere in Plato’s dialogues. D’Angour argues that the other woman, the priestess Diotima in Plato’s Symposium, is a fictionalised version of Aspasia. Socrates claims that Diotima has taught him ‘all I know about love’; this is surely a clue to his real feelings for Aspasia.

On the basis of this and scattered remarks in later sources, D’Angour ‘imaginatively reconstructs’ the history of their relationship: Socrates fell in love with Aspasia as a young man; she rejected him for Pericles; and, ‘seeking to assuage his disappointment’, she introduced him to the method of deriving general definitions from particular examples which would form the basis of Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy. But while it is plausible that Aspasia contributed more to 5th-century intellectual life than the sources credit her with, the details of D’Angour’s account are pure speculation.

Less momentous but no less speculative is the claim that the young Socrates was not bulging-eyed or pot-bellied as he was in maturity, but a ‘physically impressive’ teenager, and even a ‘notably robust baby’. The main evidence for this claim is his participation as a hoplite in three military campaigns (as described in Plato’s Apology) in his thirties and forties. And Henry VIII, though rotund in middle age, was ‘famously good-looking and athletic in his youth’.

One of Socrates’ quirkier characteristics, his ‘divine sign’ or inner voice, may, suggests D’Angour, have been a form of psychosis, attributable to the trauma which may have been caused by his being beaten as a child by his father. His bulging eyes may have been due to hyperthyroidism. Many ‘mays’ — but no actual evidence.

‘Perhaps what evidence there is could be extracted and a film made about the unknown Socrates,’ the author suggests in his afterword. He supplies a potted Life, printed in italics to show that it is, as they say in the industry, ‘based on a true story’. The narrative, if a little donnish where the philosophy is concerned, is Hollywood in style (‘Ten years have passed since the Persians withdrew from Greece…’), with sensational love interests (‘Socrates encounters an extraordinary person who will change his life forever’), epic conflicts (‘he serves on the gruelling three-year campaign in Potidaea’), and political intrigue (‘Socrates’ foes gather their forces’) leading to the hero’s downfall.

D’Angour leaves one with the impression that his Socrates is less a historical reconstruction than another myth, conceived, like so many before it, under the spell of Plato.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in