In March 1968, Frank Zappa released an album called We’re Only in it for the Money. Presumably, then, Zappa — who died a little over a quarter of a century ago — would be delighted to discover that he begins his latest tour next month, with a series of shows in the US followed by a visit to the UK in May, including a show at the Palladium in London.

Zappa will be appearing in holographic form, using footage filmed in a Los Angeles rehearsal space in 1974, his disembodied voice backed by a live band. The show is to be made up of ‘footage that no one has ever seen, as it has been locked in the vaults since the early 70s,’ says Jeff Pezzuti of Eyellusion, the company that produced the hologram.

‘As a futurist, and hologram enthusiast, Frank fearlessly broke through boundary after boundary as an artist, and in honouring his indomitable spirit we’re about to do it again, 25 years after his passing,’ said Zappa’s son Ahmet.

Well, he would, wouldn’t he? But bear in mind that in 2016 another Zappa offspring, Dweezil, told Rolling Stone that the Zappa Family Trust — of which Ahmet is a trustee — is ‘beyond broke’, and it’s hard not to suspect, perhaps, that that 51-year-old album’s title was on the nose.

The music business has, of course, never been anything but fairly tawdry. It’s always been every bit as much about the business as the music. Ever since Elvis Presley’s death in August 1977, when seven singles charted simultaneously, it has been recognised that death is one of the shrewdest career moves an artist could make. But at that point the gain was sporadic: a few weeks of massively boosted sales, followed by regular reissues of greatest hits albums.

Now, though, we’ve entered an age when the combination of mortality, declining record sales and technology has led to the opening up of new frontiers in the exploitation of artists’ catalogues and legacies.

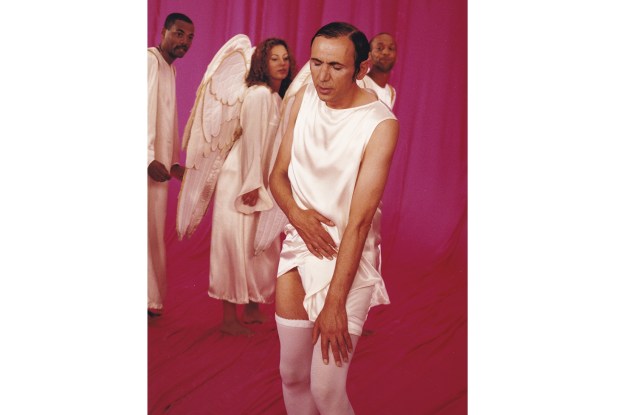

Zappa’s isn’t the first holographic tour: he’s been preceded by Roy Orbison (complete with orchestra) and by Ronnie James Dio, who sang with Rainbow and Black Sabbath (in a show also produced by Eyellusion). Billie Holliday performs seven days a week at the Hologram USA Theater in Los Angeles, in a ‘staggering hologram performance featuring biographical stories and supported by stunning dance performances’. Tupac Shakur appeared in holographic form at the giant Coachella festival in California in 2012. Expect more to follow, even if it was announced last month that the forthcoming Amy Winehouse holographic tour has been cancelled owing to ‘some unique challenges and sensitivities’.

While the Tupac hologram was something unusual — not just old footage of the rapper, but digital film of an actor with an animated head, and newly recorded voice impersonations (allowing ‘Tupac’ to greet the crowd with ‘What the fuck’s up, Coachella’ and to interact onstage with the very-much-alive Dr Dre and Snoop Dogg) — there’s something fitting about the fact that it’s far more common for these holographic artists to be reincarnated using a trick that’s not new, but actually positively old.

Pepper’s ghost was first revealed by John Henry Pepper in 1862, using angled glass to reflect an image from one lit room into another darkened room (in this case, the stage), creating the effect of a ghost appearing before the audience. More than 150 years later, it’s still fundamentally the same, albeit with higher-tech equipment — a DLP (digital light processing) projector, an HD video player, an LED screen. Pezzuti told me it was a variant of Pepper’s ghost, with the added ‘secret sauce [of] how we digitally recreate an artist’ (naturally, no one wants to reveal all the secrets of their productions).

But there are drawbacks. Danny Betesh, who promoted the holographic Orbison tour last year, said the star could only be seen from head-on, which meant that seats at the side of arenas couldn’t be sold.

Don’t expect this technology to remain the preserve of the dead either. We’ve already seen some special one-off performances from holograms of living stars — a holographic Madonna appeared with Gorillaz at the 2006 Grammy awards. But with the music industry always searching for new revenue streams, that could become more commonplace.

‘We think this is a major growth opportunity for live music,’ Pezzuti told me. Artists who have retired can continue to ‘“tour” all over the world, and not have to actually physically tour. It’s the way the industry will head, as the songs and these legacy acts are so beloved that fans will continue to come and support.’

Crucially, too, once you have the hologram built, you have the show. There’s no worry about whether the artist will be in a fit state to show up, no inconsistency from gig to gig. It is, literally, plug in and play. ‘We have created a two-hour show that can play for years and that’s where the cost economies really come into play,’ Pezzuti says. There’s just ‘a one-time initial investment to create the show, and then it can be out for as long as needed. We can continue to add content to the show and then each tour can be renamed and rebranded. It can be profitable very quickly. Obviously, it is a volume-based model, so the more it tours, the better it does.’ Kerching!

You might think this is all a little bit grisly. You will be unsurprised to hear that those behind the tours disagree. ‘They’re iconic figures with great songs that people want to relive,’ Betesh told me. ‘People want to see this sort of thing. I think it’s like memorabilia — it brings back memories. [The Orbison tour] came with the full backing of his three sons. The fact is it has their full support — it wouldn’t happen without them.’

Indeed, Roy Orbison Jr told me it’s all part of a grand plan, running alongside documentaries and albums featuring his father’s classics with new backings from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (two have been released so far). His ambition is to have the holographic Orbison headline one of the big shows that take place in London each summer — 65,000 people watching a long-dead performer. The result of all this activity? ‘We sell more T-shirts and have more people going to Roy’s Facebook page; radio play is up.’

That’s the key point here. The holographic tour is just a means to an end, and that end is the continual monetisation and exploitation of a dead artist’s catalogue. Orbison became the first dead star to go out on the road in support of a new album, when he followed the release of A Love So Beautiful — his first album with the RPO — with his first holographic tour. There hasn’t been an Elvis holographic tour yet, but a flatscreen projection of him — again, accompanied by orchestra — went on a sellout arena tour of the UK in support of his own album with the RPO, The Wonder of You.

Maybe Elvis, Orbison and Zappa would have been happy about all this. Certainly their families are. But there are times when you can be pretty sure a dead artist would not have approved of what is being done in his name. Take Prince, who once described the use of technology to allow dead performers to appear alongside living ones on stage as ‘the most demonic thing imaginable’, and whose desire for complete artistic control over everything he did was legendary. However, it didn’t stop a giant projection of him — licensed by the Prince estate — appearing with Justin Timberlake at last year’s Super Bowl halftime show.

It’s only going to get less appealing from here, as technology advances, estates become increasingly desperate (those legal fees don’t pay themselves, especially when there are several dozen people arguing about who should be the true heir), and rock and pop become ever more mired in a celebration of the past. Rock’n’roll will never die. Even if it wants to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in