Every day our age seems to be getting madder and madder, in defiance of the notion that man is a rational creature and of the even more risible Whiggish narrative that we’re on a path of continual progress.

I’ll give you some examples: the murder of women’s sport by the transgender agenda; the rejection of nuclear power in favour of renewables; HS2; the possible prosecution of the Bloody Sunday paratroopers; the articles celebrating Shamima Begum as a victim; the idea that only gay actors should play gay characters; the government’s wilful rejection of the biggest popular mandate in British history.

I could go on, as I’m sure could you, but I won’t because it’s too depressing. Instead, I want to tell you about a marvellous book, now celebrating its 50th anniversary but still hugely fresh, perceptive and readable, which will help you put all these horrors into perspective and teach you to be more philosophical: Christopher Booker’s 1969 classic The Neophiliacs.

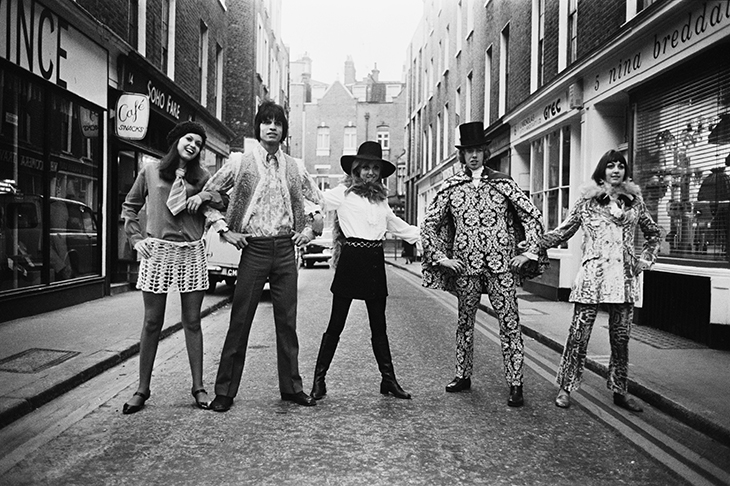

It’s a book that works on many levels, the most basic being a social and political history of the Swinging Sixties. As a key player in the satire boom — he was founding editor of Private Eye and a political scriptwriter of That Was The Week That Was (aka TW3) — as well as a jazz critic and a Spectator columnist, Booker helped to invent and define the era.

But by the time he wrote The Neophiliacs, he’d evidently grown wary of the monster whose creation he’d been part of. ‘Much of it was amateurish, juvenile and completely stereotyped in attitude,’ is his verdict on TW3 . And he’s similarly scathing about James Bond, David Bailey, the Beatles, pop generally, Mark Boxer, the collected works of John Osborne, the miniskirt…

Certainly, The Neophiliacs is a bracing corrective to the notion drummed into my own generation (b. 1965), that if you hadn’t fully experienced the 1960s you really hadn’t lived. Booker does not accept the fashionable line that this was the decade when we became more liberated, more modern, less hidebound by fusty dogma. On the contrary, he thinks it was the beginning of the nightmare from which, half a century on, we are still struggling to awake.

Underneath all the scrupulously documented social history, though, Booker has a much deeper, more ambitious point to make: there was nothing unique about the 1960s revolution. Rather it was just another manifestation of the bouts of collective psychosis to which our species is periodically prey. The 1960s were just a re-run of the 1920s Jazz Age, which in turn was a version of the Romantic movement. But the parallels go back further than that. The term ‘square’, for example, originated not as a 1960s insult for people who weren’t hip, but rather from 1770s London as a coinage for all those ridiculously old-fashioned sorts who still wore square-toed shoes.

‘Just as few adolescents can ever believe that their parents have been through the same stages of attitude and development before them, so one of the more frequently recurrent fallacies has been people’s belief that their own age is without precedent,’ Booker scornfully observes early on. He proceeds to demolish this delusion, by showing how again and again we make the same mistakes — the result of a human predisposition to favour fantasy over reality.

On the individual level, this tendency is usually pretty harmless, manifesting itself primarily in the Walter-Mittyish daydreams many of us enjoy about being richer, more successful, more sexually attractive than we are. But in its collective form, it can be absolutely disastrous, leading to such otherwise inexplicable bouts of destructive and ultimately suicidal upheaval as the French and Russian revolutions and Nazi Germany.

According to Booker’s persuasive account, every significant movement in history can be explained in this way. And so too — as he demonstrated in his subsequent masterpiece The Seven Basic Plots — can every work of literature (storytelling being our way of explaining and formulating human experience and behaviour).

In every case — whether François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim, Ravel’s Boléro, the Suez Crisis or the Swinging Sixties — we move through five clearly identifiable phases of the fantasy cycle: the Anticipation stage; the Dream stage; the Frustration stage; the Nightmare stage; the Death Wish stage.

Take the rise and fall of Hitler, whose Anticipation (‘looking for a dream-focus, a cause, a release’) began in the 1920s; then moved to Dream with the conquest of France (‘rising excitement when, as in a daydream, everything seems to be going right’); thence to Frustration with Stalingrad and El Alamein; Nightmare in 1944 ‘with forces closing in on Germany from three sides’; and finally, inevitably, to the Death Wish with the bunker and the Third Reich’s Götterdämmerung.

I’m very much looking forward in my next phone chat with Booker to hearing his explanation as to how our own weird times fit into this fantasy cycle. On Brexit, I suspect he’ll argue that we’re well past the ‘bliss was it in that dawn to be alive’ Dream moment (well for some of us, anyway) on 24 June 2016, and that we’re now fast headed for the Death Wish final reckoning.

At the risk of misinterpreting Booker’s work for my own self-gratifying fantastical purpose, my reading of The Neophiliacs leads me to a more optimistic position. If, as Booker suggests, history moves in cycles and if ideas — be they Nazism, miniskirts or skiffle — acquire a momentum which individuals are powerless to resist no matter how much they might deplore the terrible new trend, then two things surely follow.

One: no matter how much we all may fret, there’s not a single damn thing any one of us can do to avert the inevitable so we might as well relax and enjoy the ride.

Two, Brexit is going to happen come what may. And if we are in the Death Wish denouement, well, that’s the way of the world. At least it means there’s a lovely Anticipation stage and Dream stage waiting for us to luxuriate in again some time soon.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in