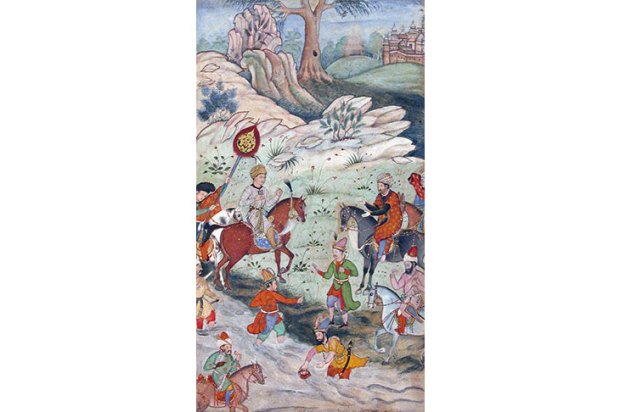

I can only remember one page of any of the dozens of Ladybird histories that I read avidly as a child: an illustration of a scene from the Third Crusade, when Richard the Lionheart, at the head of his Christian army, met Saladin, the leader of the Muslim forces, outside the port city of Acre in 1191.

The picture does not show the battle but the two men comparing swords, like top level sportsmen discussing preferred bats or rackets. They were standing before a tent, broadly medieval in appearance. On the ground lay an iron bar, evidently chopped in half with a single blow from the great broadsword between King Richard’s mailed fists. A silk scarf floated in the air and Saladin, slender, saturnine and subtle, was preparing to slice it in half with his razor-sharp scimitar.

So much in one picture: the East and the West, muscular Christianity and oriental finesse, a chivalrous meeting of equals on the battlefield.

It was rubbish of course, as Jonathan Phillips’s fascinating, authoritative and intelligent biography of Saladin, or Salah al-Din ibn Ayyub to give him his full, honorific Arabic name, makes amply clear. Though they did confront each other across a battlefield, the two leaders never met. The scene was entirely fictional, as are stories of single combat, of a disguised Saladin sneaking into the crusader camp to heal a sick Richard, or of Saladin’s passionate affair with Eleanor of Aquitaine. This latter was enthusiastically reported in The Royal Mistresses of France, Secret History of all the Amours of all the French Kings, published in 1695. The author explained the attraction of the Kurdish-born potentate thus: ‘’Twas said of him he was a person well-shaped, nimble in all manner of exercises, valiant, generous, liberal, courtly, and in a word, that he was endowed with French manners.’ How times change.

This excellent book explores both the man — who famously defeated the crusaders at the battle of Hattin and took back Jerusalem in 1187 — and the myth. Phillips, a professional historian who specialises in the history of the crusades, first takes us deep into the Near East of the 11th and 12th centuries, a world of such spectacular fragmentation, complexity and dynamism that it makes the region’s current tumult seem tame by comparison. It was this environment that Saladin had to navigate. As Phillips shows, religious solidarity often counted for little, or actively promoted intra-faith violence.

Saladin’s greatest gift was not for war but diplomacy. He was brave enough, leading from the front on occasion, and a good general, but his real strength was for coalition-building, using all manner of incentives to bring potential enemies round and to coax men and money out of allies. The fees lavished on court poets who would broadcast his virtues were well spent. Also worthwhile was Saladin’s vigorous support of religious institutions for much the same reason. Reliance on family members, such as his brother Saphadin, turned out to be key, as were generous handouts to able loyalists. By the later decades of the 12th century, the call to jihad and the duty of able-bodied Muslims to engage in holy war constituted a fundamental part of his success. So too did carefully calibrated and spectacular violence — executions, massacres and the harsh repression of revolts.

Nor, lest anyone should think otherwise, were the crusaders paragons of virtue. Phillips writes:

While the religious aspect certainly triggered the expeditions, status and honour were central to the lives of kings, nobles and knights; being seen to lead and to participate in brave acts of holy warfare were strong attractions. Other warriors were mercenaries, Christian men who had signed up to the campaign primarily to earn a living… Many took part because their master told them to.

Saladin died in 1193 (on about page 400), and the rest of the book will be useful to anyone trying to draw connections between events 800 years ago and today.

First, Phillips charts western perceptions of Saladin. In the aftermath of the fall of Jerusalem, he was seen as a man of evil, ‘sated with Christian blood… the whore of Babylon’ and depicted as a head of the Beast of the Apocalypse. He was also accused of being a pimp, a less sensational but equally unfounded accusation.

But even his detractors were aware that Saladin had spared Jerusalem when he recaptured it. This may have been simply because he wanted ransom and slaves, but it was nonetheless a significant contrast to the Christians of the First Crusade, who had massacred all the holy city’s inhabitants. As diplomatic interaction between leaders intensified, some European nobles began to see that neither Saladin nor the Muslims they encountered matched the familiar caricatures. Instead, there was admiration for his courage, culture and even faith, and a new image of Saladin took shape. The battle of Hattin had been a crushing defeat and required a worthy opponent.

By 1208, a German court poet was praising Saladin’s generosity, and soon romantic tales began to circulate about how a minor noble from northern Iraq, who grew up in Damascus, was in fact descended from a powerful aristocratic family in northern France. Dante includes Saladin among the three Muslims allowed into a castle reserved for noble pagans in the first circle of Hell, alongside the philosophers Ibn Sinna (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). There are flattering accounts in Boccacio’s Decameron and he gets a positive mention in Petrarch.

Four centuries later, Voltaire is something of a fan, and Gibbon offers a sensitive portrait of an ambitious but merciful man. Finally, there is Sir Walter Scott, who flipped the usual portrayals of Richard and Saladin to show the former as cruel and violent, the latter as a true prince, and probably had more influence than anyone in constructing the Saladin I found in my Ladybird history.

Among inhabitants in the Near East, Phillips argues, Saladin and the crusades did not disappear from collective memory and tradition as some have argued. Ibn Khaldun, the 14th-century historian, intellectual and diplomat, praises Saladin as an exceptional figure. Other contemporary chroniclers and historians recount his just rule too.

But it was when European imperialists arrived en masse that the ghost of Saladin — who had united the disparate peoples of the region in a successful campaign against western invaders and reconquered Jerusalem — really rose from his tomb in Damascus. In 1858, one of the first local-language newspapers in the Muslim world reprinted an admiring account of Saladin’s life from the 13th century. As nationalism began to take hold throughout the Middle East, Saladin became the subject of plays and novels too. Both Arabs and Kurds claimed him as their own, and the growing opposition to Zionist settlement in the Near East cited his as an example to follow.

Arab nationalists invoked Saladin in the immediate postwar period too, some calling for a new ‘battle of Hattin’ to expel the modern crusaders; and Gamal Abdel Nasser, the soldier who seized power in Egypt in 1954, frequently spoke of Saladin’s victories as the basis of Arab unity. Saddam Hussein let no one forget that he shared his birthplace, Tikrit, with Saladin and had portraits of himself as an Arab warrior put up all over Iraq. In Syria, Hafez al Assad put Saladin on banknotes and raised statues of him.

Islamists also see Saladin as an inspiration. Osama bin Laden mentioned his ‘all-conquering sword, dripping with the blood of infidels’, as did the anonymous author of the strategic jihadi text, The Management of Savagery, which was a significant influence on Isis. In 2015, a report found that more than 71 per cent of the jihadi propaganda in the Middle East surveyed emphasised the ‘nobility’ of jihad, often mentioning Saladin.

A misconceived vision of Islamic history as much as a distorted version of the Islamic faith is central to this ideology. A mistaken vision of the crusades is key to the growing white supremacist movement and its various less extreme offshoots. Both show us once again that it often isn’t what really happened that has an impact on contemporary events but what enough people think happened. That is a problem.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in