A looming Australian federal election and the increasingly bitter carbon wars have resulted in a series of campaign promises that are even madder and more destructive than the usual attempts by politicians of all sides to be seen to be green.

These include Labor pledging to ensure that half of all new cars sold will be electric by 2030, and that half of all electricity generated will be from renewable sources by the same year.

Another Labor promise to introduce a scheme to curtail emissions from Australia’s top 250 emitters is arguably a warning to industrial companies not to bother investing in the country, but at least is not obviously impossible to achieve.

The electric car policy in particular, trumpeted as Australia’s first such policy, was warmly welcomed by green activists and the media but is a flight of fantasy. At best the policy will cost consumers and taxpayers billions a year, and at worst might cause the car industry to grind to a halt.

A motor industry statistics service, VFACTS, reports that 1.15 million light vehicles were sold in Australia in 2018, or 3 per cent less than the record sales year of 2017. A major feature of the market is the continued shift to SUVs, which now account for 43 per cent of the market, at the expense of ordinary passenger vehicles. In 2017, the latest for which detailed figures are available, electric cars accounted for about 0.2 per cent of sales.

The continuing popularity of SUVs often puzzles industry commentators as it is known that the vast bulk of these cars, designed to go off-road as much as on roads, will never be used on any surface rougher than gravel car parks.

Various explanations for that popularity centre on the extra size of the vehicles. More people and their accessories can be crammed into them for excursions such as trips to the beach. As they are higher off the ground they are easier for consumers with limited mobility (older people) to get into and out of and, when out on a highway surrounded by trucks, consumers feel safer than when in a passenger car – or a tiny electric vehicle. The additional safety may be illusory, but it remains a selling point.

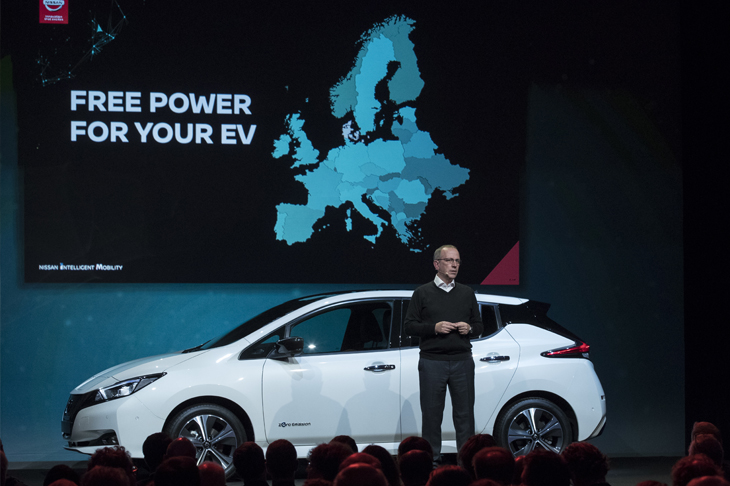

One way to overcome the problem of consumer reluctance to buy the generally smaller electric cars, which are also usually more expensive and have limited range compared with petrol cars, is simply to throw taxpayer money at the problem. In Norway, for example, purely electric cars accounted for 31 per cent of new car sales in 2018, and hybrids another 18 per cent, thanks to the Norwegian government offering a host of incentives including dropping the huge taxes it imposes on petrol cars, such as a 25 per cent value added tax, free recharging at power stations and excusing electric vehicles (EVs) from road tolls.

The last concession is extremely significant in parts of Norway which has an extensive, and expensive, network of highways and tunnels.

The Financial Times in the UK has estimated that all these concessions and tax breaks add up to half the cost of each car.

Similar stories of EV sales being bought by government incentives can be told in Denmark, China and California among other places. In Denmark, EV sales plunged when subsidies were cut at the end of 2015.

None of that translates readily to the Australian environment but if the government tried enticing consumers away from their SUVs by offering incentives worth perhaps $10,000 for each car sold, in direct subsidies or loss of tax revenue, that very low guesstimate multiplied by 550,000 new cars (half of 1.1 million) works out to $5.5 billion a year.

Then there are all the public funds that would have to be spent on building recharging stations (Norway has two charging stations every fifty kilometres on main roads).

This raises the question of why Australia, as a country, would spend so much to make consumers part with their SUVs, rather than improve public transport which is generally acknowledged to be more cost effective in reducing emissions. The Norwegian government has considered scaling back the immense concessions for EVs, incidentally, but concluded that the electric car market would not survive if it did.

Labor’s policy would seem to sidestep the problem of forcing consumers into electric cars by also imposing average emissions standards on the cars sold by dealers. To meet those standards, dealers would be required to sell a certain number of no-emission electric cars to offset the higher emissions from other cars. The problem of getting consumers to buy EVs, when so few are on Australian roads, very few charging stations are available and the cars are still priced well into the middle and upper part of the consumer market, then becomes a problem for the dealer.

The automotive industry has complained that the policy is unworkable and will result in serious distortions in the market.

Another major problem with this bizarre policy is that the vast influx of EVs will have to be kept charged by an electricity grid that will come under increasing pressure to cope with an unrealistic level of green energy to be forced on to it.

As has been pointed out previously in this magazine, ‘The unacceptable cost of renewables’ (December 9, 2017) and ‘Renewables becalmed’ (July 7, 2018), the Australian grid is already struggling to cope with existing levels of renewable energy. On hot days when demand soars, major industrial users are being paid to stay off the grid.

In Europe and the US grid operators can sidestep the problem of mad levels of renewables by importing electricity from adjacent countries or because the larger, denser networks have greater reserves. In contrast the Australian east coast grid (Western Australia is separate) is spread over an area comparable to that of Europe or the US’s eastern seaboard, but with only a tiny fraction of the generating capacity.

These policies add up to another, major reason not to invest in Australia.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in