Cuba meant a lot to Graham Greene. Behind his writing desk in his flat in Antibes he had a painting by the Cuban artist René Portocarrero, presented to him by Fidel Castro, who had signed his name on the back, so that Greene didn’t know which way to hang it.

Another prize possession was a tatty Penguin copy of Our Man in Havana, kept together by Sellotape, which the Russian cosmonaut Georgy Grechko had read in outer space, and in which, while circumnavigating our planet, Grechko had underlined the places in Havana that he had visited. ‘I’ve been reading it all my life, both on earth and in space,’ he wrote in his inscription when presenting the paperback to Greene in 1985. ‘I’ve learned it by heart.’

Greene’s 1958 novel, filmed soon afterwards by Carol Reed, was a satire of British foreign policy in the wake of our national humiliation over Suez — so not a world away from the situation we face today. The antithesis of the suave, womanising James Bond, who had made his debut five years earlier, James Wormold is an expatriate vacuum- cleaner salesman with a limp and an extravagant teenage daughter, whose American wife has left him.

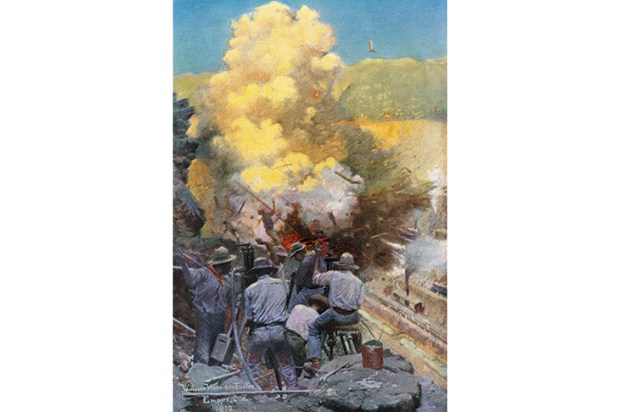

To fund his daughter Milly’s horse-riding during the fag-end of Batista’s dictatorship, Wormold allows himself to be recruited by British Intelligence for their Caribbean network as Agent 59200 — the same number given to Greene in 1941 when SIS posted him to Sierra Leone. Frantic to impress, the austere Wormold is driven to concoct sub-agents and intelligence, finally inventing ‘big military installations under construction’ in the mountains of eastern Cuba. Back in Whitehall, the plans that he submits as proof of these, and modelled on his Atomic Pile vacuum cleaners, are hoovered up with the same gusto as Tony Blair in 2001 swallowed colour sketches of supposed biological trucks drawn by an Iraqi ‘sub-source’ codenamed Curveball.

Christopher Hull is a footslogging, down-to-earth lecturer in Spanish and Latin American studies at Leicester University, who has written what he calls ‘the story behind a story and the story that follows the story’. It is the kind of obsessive book I like best — a full-body immersion into Greeneland, which may overwhelm the uninitiated but delight his most committed readers, in the tradition of Tim Butcher’s Chasing the Devil, which retraced Greene’s five-week walk with his cousin Barbara through West Africa. No detail for Hull is too small, from the room numbers of Greene’s various hotels, to the cost of his daiquiris at Floridita, his favourite restaurant, to the models of the aircraft that landed him in Havana on 12 visits (double the previous estimate) between 1938 and 1983, in the protean guises of holidaymaker, novelist, screenwriter, journalist and — ultimately — intelligence gatherer. It is one of several satisfying symmetries that Hull teases out: how the author of an iconic spy novel that prophesied the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 may himself have ended up spying on post-revolutionary Cuba for SIS.

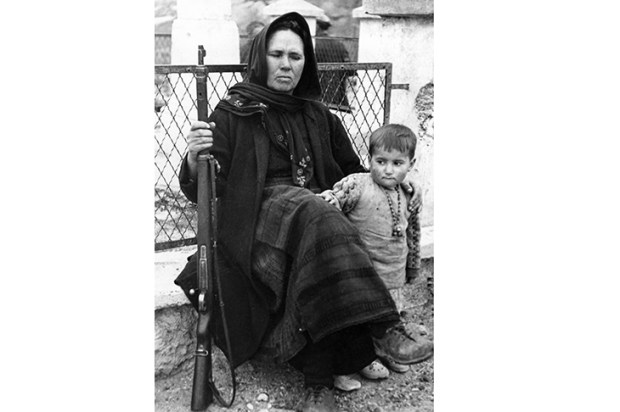

Like its author, Greene’s novel, too, underwent a few incarnations, beginning life as a film treatment set in Estonia, after a journey that Greene made in 1934. British ex-pat Richard Tripp, who sold sewing machines in Tallinin, while inventing agents and conducting arms sales, was inspired by a former Anglican priest, Peter Leslie, but the character of Wormold borrowed much from Greene’s feckless elder brother Herbert. An impressively ineffectual spook who became an agent for the Japanese (they paid him £2,000 a month, despite being ‘rather disappointed with the results’), Herbert then offered his dubious services to the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, whereupon he was swiftly captured. In one improbable story, Hemingway was all set to execute him as a spy, but Claud Cockburn allegedly interceded: ‘Don’t shoot him, he’s my headmaster’s son.’

Greene drew on Herbert for the bounder Anthony Farrant, a formervacuum-cleaner salesman, in England Made Me (1935), and so was somewhat startled when his bohemian friend Julian Maclaren-Ross told him three years later how he dabbled in door-to-door vacuum cleaner sales in Bognor Regis, ‘carryingthe unassembled parts of the appliance in a golf bag’.

In the creation of fictitious intelligence, Greene had personal experience. When in Sierra Leone, he had tried to set up a roving brothel in Portuguese Bissau, ‘where prostitutes could pick up loose bar- and pillow-talk’. Posted back to London, he compiled a card index of operatives in Portugal, including Paul Fidrmuc, codenamed Ostro, who invented agents ‘simply to make money’, and the better known Juan Puyol García, codenamed Garbo, who fabricated an entire network from a library in Lisbon, one of his 27 agents in Britain being ‘an itinerant Gibraltarian waiter who spied on a subterranean munitions depot in the Chislehurst caves’.

These loose strands came together, writes Hull, during an unplanned visit to Havana in 1954, where Greene was deported after admitting to US immigration that he had briefly been a member of the Communist party.

Havana, in those days, was still a city of vice, with sex artists like Superman, possessor of a penis of legendary dimensions, who performed nightly at the Shanghai Theatre. Something in Havana’s air, reckoned an article in Esquire, ‘has a curious chemical effect on Anglo-Saxons, dissolving their inhibitions and intensifying their libidos’. Greene was enthralled by its seediness, ‘its looseness and its strangeness’. The ‘seawet’ Malécon was a tropical twin of the promenade in Brighton, a city he loved as well for ‘the sea, a sense of fun & the unexpected’. He later holed up in Brighton’s Hotel Metropole to write the screenplay.

Batista was still in power when Greene began writing Our Man in Havana in the Hotel Seville-Biltmore. (Norman Lewis was also staying. ‘I used to be in the bar,’ Lewis told me, ‘a ghastly American blue-lit bar, and [Greene] used to sit in the corner under this blue refulgence, and say the people reminded him of parachutists about to take off.’)

On Greene’s subsequent visits, Cuba was in Castro’s hands; bureaucracy had replaced corruption and the people queued for food. At the Floridita, cradle of the daiquiri, there were no limes to make the national cocktail and a bad bottle of rum cost $122 and was nicknamed ‘rat poison’.

Vice was in shorter supply still. Kenneth Tynan complained of the clean-up that ‘the Amish had taken over Las Vegas’. Unable to locate Superman, an otherwise sympathetic Greene observed: ‘Revolutions are so puritanical.’ To the end of his days he admitted to being ‘very much of two minds’: whether to put on open display his admiration for Castro’s ‘courage and efficiency’ or condemn his ‘authoritarianism’, which had imprisoned homosexuals such as Portocarrero.

There are perils in following Greene’s footsteps too closely: his biographer Norman Sherry went mad. Hull treads the windy side of sanity. He is capable of veering between the dizzily literal and the wildly speculative (‘surely we can assume, ‘it is logical’, ‘it is possible’), but for the most part he keeps on track.

As a huge admirer of Greene, I cherish two encounters in particular that Hull describes. The first is with Hemingway, a perfunctory meeting in Sloppy Joe’s reduced to the single word ‘Howdy’. Restrained from the chance once upon a time of shooting Greene’s brother and perhaps adding his head to the big-game trophies on the walls of the Finca Vigia, Hemingway regarded Greene as ‘a whore with a crucifix above his bed’ who was trampling on his patch — while Greene nursed contempt for the American writer’s ‘hairy-chested romanticism’.

The other imperishable encounter is with Castro, ‘a Chestertonian man’, after a comical chase worthy of Wormold. In the course of two long meetings, Fidel questioned Greene closely on the topic of Russian roulette, his knowledge of Spanish wines and his regimen — ‘he did not exercise and ate and drank whatever he liked’ — before making Greene this offer, along with the painting by Portocarrero: “If you have to leave France come and live here.”’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in