Gerald Martin’s titanic biography of 2010, Gabriel García Márquez: A Life, was the product of 17 years of research and 300 interviews, including one with Fidel Castro. So what does Solitude & Company add to the fairytale history of ‘Gabo’, as Latin America’s greatest teller of historical fairy tales is generally known?

In the year 2000, when García Márquez was still alive, Silvana Paternostro began conducting her own interviews with Gabo’s family, his ‘first and last friends’, his agents, editors and fellow writers. She has now cut, spliced and transcribed the tapes in order to create the effect of a bar full of drunks interrupting one another. ‘Is that tape recorder off?’, asks Quiqui Scopell, a photographer. ‘Leave it on!’

The model for the book is George Plimpton’s Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall his Turbulent Career, and García Márquez is as suited to the vox-pop treatment as Capote was. What is grandly called oral history and otherwise known as gossip (‘This isn’t for you to repeat,’ confides one of the revellers) was described by García Márquez himself as ‘fiction about fiction’; and it becomes clear, once you get to know his muckers, where Gabo got his gift of the gabo.

He comes from a culture in which everyone tells stories or, as Quiqui puts it, ‘talks shit’. One of Gabo’s oldest friends goes off on a riff about another friend who kept a pet cricket called Fififififi — ‘listen, this is true!’ — who told his master one day that he had made his lunch: ‘Maestro, maestro, I prepared something for you’, at which point maestro put Fififififi into his mouth and swallowed him.

Solitude & Company divides into two parts. The first tells the story, through Gabo’s siblings and early ‘arguers’, of how the youngest of 12 children, born in 1927 to what a distant cousin described as a family of witches, was raised by his grandparents in Aracataca, which sounds suspiciously like Abracadabra and became, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the magical town of Maconda. Having read so many books that his family feared ‘he would lose his mind’, Gabo then dropped out of law school to become a journalist, after which he started to write fiction based on the stories he had grown up with.

He then, aged 39, gave up his job, borrowed money and isolated himself for eight months in a bare room with a type-writer in order to write the great Colombian novel. ‘His entire family,’ says Emmanuel Carballo, who read One Hundred Years as the chapters appeared, ‘his wife, his sons, his friends, we all made an empty space around him because he was frenetically dedicated to one thing.’

The reason why Gabo chose Carballo as his first reader was because, explains Carballo, ‘I’m very talented.’ One Hundred Years was ‘made’, Carballo continues, ‘with a superhuman gust of wind’, an image repeated by Rodrigo Moya, who says that, according to García Márquez’s wife, when Gabo was writing a particularly intense part of the novel ‘his face swelled up. The process of a work like that is

a little superhuman, and so those things happen’.

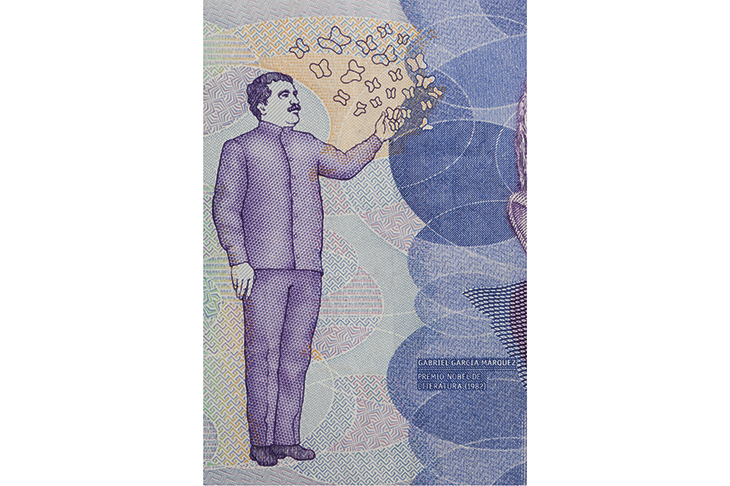

According to Maria Luisa Elio, the dedicatee of One Hundred Years, Gabo ‘knew’ the book was ‘a marvel’; but according to Guillermo Angulo, his friend from his impoverished Paris days, Gabo knew nothing of the sort: ‘In fact he was very doubtful that it would be a good novel.’ Maria Luisa Elio thinks the novel was ‘really good’ but not ‘to that degree’ — by which she means, as Gabo’s godson Santiago Mutis puts it, the degree to which ‘everyone kneeled down before him’. ‘And now,’ says Quiqui Scopell, well into his drink, ‘they dare to compare that Hundred Years to Don Quixote.’ That Hundred Years, he continues, is ‘a bad, folkloric novel’ in which ‘yellow butterflies jerk off’.

The second half of Solitude & Company explores the effect on his old friends of ‘Gabolatry’, when García Márquez became the guest of presidents and dictators. ‘Gabito said it, so that’s it,’ grumbles Quiqui. Fame ‘attacked’ him ‘like a bull’, says his godson. ‘And then gradually, slowly, another person begins to appear.’

Most of the party agree with this, although they argue about whether the change began with the success of One Hundred Years in 1967 or the Nobel Prize in 1982. ‘The Nobel didn’t change him at all,’ says Carmen Balcells. ‘He became famous and pedantic,’ contests Emmanuel Carballo, ‘and pedantry and feeling important bother me a great deal.’ His godson, fast becoming my favourite of the crowd, says that the older Gabo is ‘much more interesting’ than the younger Gabo, because he is obliged by age to reflect on ‘how he became who he is’.

Which is what Solitude & Company does too. This superb book is biography minus the moral obligation or dutiful reverence — in other words, without the boring bits. As Quiqui puts it: ‘No! No! I’ll have this drink and we’re leaving.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in