Henry Moore was, it seems, one of the most notable fresh-air fiends in art history. Not only did he prefer to carve stone outside — working in his studio felt like being in ‘prison’ — but he felt the sculpture came out better that way too, in natural light. What’s more, he believed that the finished works looked at their best in the open air.

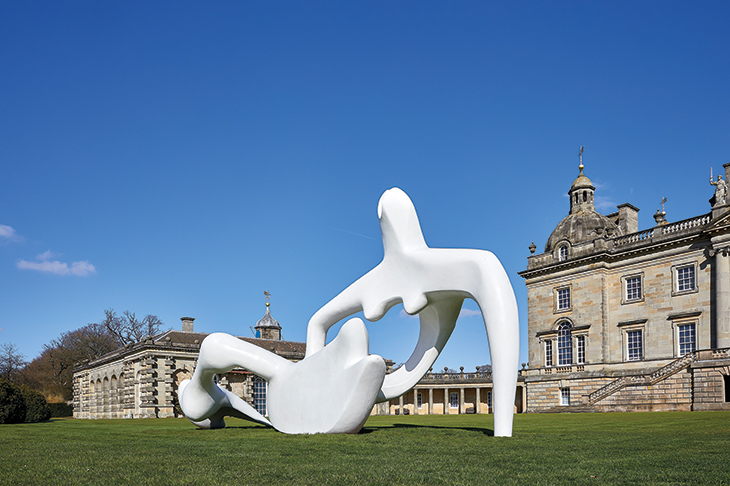

This last idea is tested in a new exhibition, Henry Moore at Houghton Hall: Nature and Inspiration — and it turns out that the artist was absolutely right. This — the latest in an enterprising series of shows at this north Norfolk mansion — is a focused selection, not a massive retrospective. Nonetheless, it prompts several unexpected conclusions.

Firstly it suggests, as he himself insisted, that Moore was an outdoors sculptor (not all of them are; Moore’s old protégé Anthony Caro felt, also rightly, that his own work worked best inside, enclosed by the walls of a white cube). In fact, you are greeted by a powerful demonstration of that point as you arrive. There, parked opposite the grandly reticent entrance front, is ‘Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae’, 1968–69, in bronze: a colossal work some 24-feet long, versions of which are distributed around the world, including one outside Dallas City Hall and another in a plaza in Seattle.

It’s hard to believe, though, that it’s ever looked more in context than it does here, undulating in the spring sunshine with Palladian architecture on one side and vistas of greenery on the other. A stroll around Nature and Inspiration — which is spread around the formal garden and deer park as well as inside the house — indicates that with Moore (1898–1986) the bigger and more abstract a work is the better. And, more unexpectedly, that he reached his peak as an old-age pensioner.

This is not conventional wisdom. The critical focus is usually on Moore’s earlier phases: his youth as an Epstein-inspired carver, the neo-romantic period drawing on the Tube during the second world war, and the reclining figures and family groups deposited on many a housing estate or skyscraper frontage in the post-war years. By that time, Moore was virtually the official sculptor to the welfare state.

I went to school in Bishop’s Stortford, near his Hertfordshire studio, and remember him being pointed out as he pottered around the local shops: a famous man. By that time, as the trail of ‘Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae’ clones around the globe implies — there are other examples in New York, Washington, Jerusalem and Toronto — he was internationally established: a British cultural flag-bearer. The Americans had De Kooning and the abstract expressionists, we had Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

Of course, by then, to younger artists and dealers Moore seemed very old hat. The avant-garde was absorbed with pop, op, land and performance art. Moore’s later sculptures were dismissed as so many huge bronze bubbles, blown up by teams of assistants in a light industrial manner. But perhaps that judgment was wrong.

Nothing else at Houghton quite matches that first sight of ‘Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae’, which might be Moore’s masterpiece. But the 20-foot high ‘Arch’ (1963–9) is majestic too, even though it is represented by a white fibreglass version, as the bronze is too heavy to move. It’s only when he gets more descriptively figurative, in ‘Mother and Child: Block Seat’ (1983–4), that things go awry. This simultaneously looks too much like a real person, and too little. Its head is a knobbly bulge, but one arm and hand are —weirdly — quite naturalistic.

It seemed that Moore needed to start with natural forms, but then move away from them. You don’t really need to know that ‘Arch’ or ‘Three Piece Sculpture’ were inspired by bones in order to enjoy them. What’s important is that, as he said, the sculpture has ‘a force, a strength, a life, a vitality from inside’. And these really do.

It helps that the final results are so much bigger than the source. When small Moores are put side by side with the objects that inspired them — a flint stone with a convoluted shape and an elephant skull — a curious thing happens. The pieces of art are upstaged by the model. The elephant skull, especially, is an amazing item that would also fascinate Damien Hirst. And in general the displays inside are not so strong. The array of medium-sized pieces in the Georgian Marble Hall is overshadowed by its magnificent surroundings, crammed with busts and classical antiquities.

I was reminded of the title of a painting by Howard Hodgkin from the mid 1970s: ‘A Small Henry Moore at the Bottom of the Garden’. These would look better there. In fact, I’d rather like one at the bottom of mine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in