‘Can you fly down this evening?’ she was asked by her boss in the Delhi office of the BBC. ‘Yes, of course. I have to,’ replied Ayeshea Perera, a Sri Lankan journalist. She was talking from Colombo to David Amanor of the World Service’s The Fifth Floor, which looks at current news stories from the perspective of those intimately involved with them and is always worth catching for its alternative, less formal approach and Amanor’s gentle probing to find the real story. Perera described the chaos on arriving at the airport in the Sri Lankan capital on the evening of Easter Day and the weirdness of going to see the Church of St Anthony next morning to find that from the outside it looked just as she had always known it. Only when she looked more closely did she notice the scattered shards of glass, the bloodstains on the road, and that the church clock had stopped at 8.45.

‘When you have a connection, as a Sri Lankan, it’s difficult to report the facts,’ said Perera. It’s physically and emotionally exhausting; there’s more at stake. People were thrusting mobile phones at her to prove they had been there, inside the church, when the bomb went off, showing her pictures of overturned pews and worshippers covered in blood. Others were screaming, shouting, moaning for their loved ones lost in the bombing. It was like walking into ‘a wall of raw grief,’ Perera said.

She grew up in Colombo when it was still a heavily militarised city, with roadblocks everywhere, before the civil war of 2009 put an end to the sporadic bomb attacks. As a teenager, she could be stopped three or four times just on her way to buy a takeaway after a late night out. It’s that personal knowledge which gave her report so much immediacy, tracking down individual acts of kindness, like the Muslim family who were living between two Christian households. They were holding things together, she explained, providing tea and solace for the Christians as they sat in vigil with the bodies of those who had been killed.

Last week’s The Reunion on Radio 4 instantly got my attention as Sue MacGregor brought together three of the airmen who had been shot down over Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm in January 1991 and held as prisoners of war. She reminded us that a coalition of 35 countries had joined together to drive Saddam Hussein and his Iraqi troops out of the Gulf state and that the biggest audience in American TV history had watched President Bush announcing the start of the war on 16 January. It all seemed so long ago, yet for John Nichol, John Peters and Robbie Stewart it is still as potent as if it happened yesterday.

You could hear it in their voices as they recalled the excitement of flying at just 50ft above the ground in their Tornado jets. ‘You could have been hit by a catapult,’ interrupted MacGregor. But Peters and Nichol were shot down and captured on their first mission, in the early hours of 17 January, ejecting once they realised that behind them their plane was bright orange, totally ablaze. Stewart, who was captured two days later, broke his leg when he landed and was operated on by an Iraqi surgeon who told us: ‘In the darkest of times… you can still find some good seeping into your life.’

You may remember footage of Nichol and Peters as they were paraded in front of the TV cameras, apparently reading from a script written for them in which they criticised the war. The UK press decided they were cowards who had given in to pressure, hounding their families for pictures and quotes. One reporter stuffed a mike through the letterbox at the home of Peters’s mother and asked her: ‘Do you think your son is being tortured, or is he dead yet?’

Tim Harford’s series for the World Service, 50 Things that Made the Modern Economy, has now set off in search of its second half-century of crucial inventions. Harford packs so much into his nine-minute programmes, taking us in his latest episode on the bicycle from Pierre Lallement’s hair-raising two-wheeled ride in Connecticut in 1865 to the surprising fact that world bike production has kept pace with the rise of the automobile. How did that happen, Harford wanted to know. The bicycle’s green credentials have something to do with it, and the way it has liberated women, first from their corsets and whalebones and, 150 years later, by ensuring that teenage girls in Bihar have access to education.

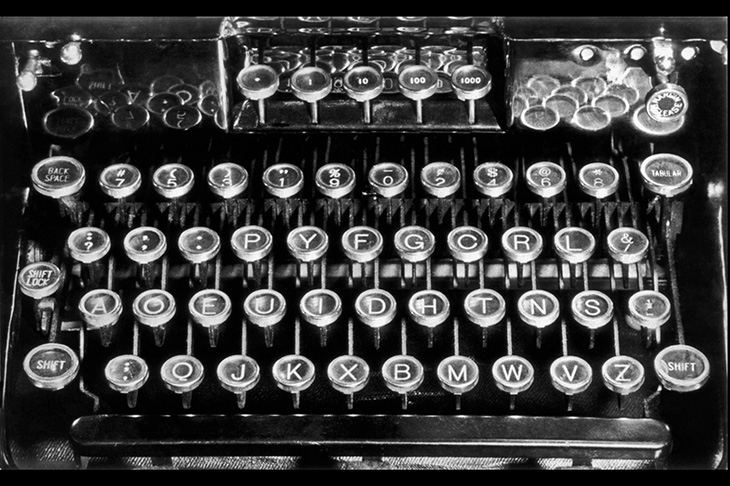

Harford always seems to ask the right questions, wondering previously why the Qwerty keyboard layout has survived given that its particular combination of letters is so awkward and that later layouts such as Dvorak are much more efficient. Qwerty was originally developed for telegraph operators as they deciphered Morse code but has never been logical for typists (was it intended to slow them down?) and even less for computer operators. If you look on your iPad you should find Dvorak as an alternative layout but no one ever switches over to it. Why not give it a try, Harford suggested.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in