It must be rare for a popular song to have such a lasting influence on a posthumous reputation. However, this is the case with Tom Lehrer’s deliciously satirical tribute, ‘Alma’. Reading Alma Mahler’s obituary in 1964 — the ‘juiciest, spiciest, raciest’ he’d ever come across — Lehrer was amazed by her matrimonial CV and proceeded to immortalise it in a catchy lyric.

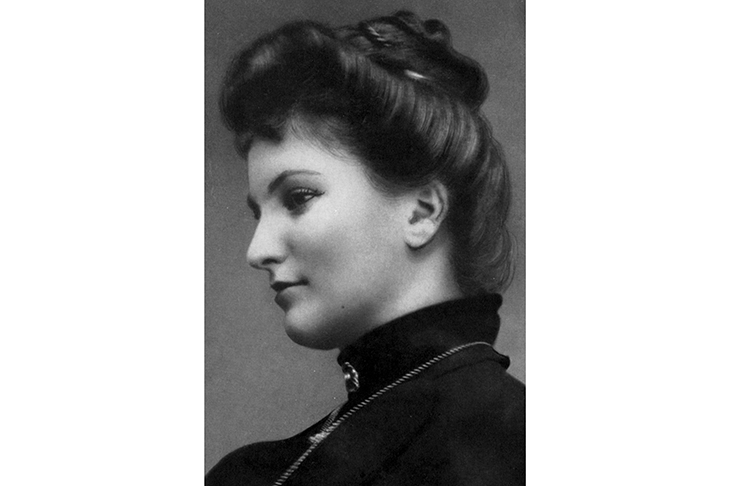

Not only had Alma been married three times, to the composer Gustav Mahler, to Walter Gropius, the founder of Bauhaus, and, finally, to Franz Werfel, author of the runaway bestseller The Song of Bernadette, she’d also managed to bag as lovers some of the top creative men in the Europe of her time. Gustav Klimt had given Alma her first kiss, while her relationship with the Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka was ‘one fierce battle of love’, full of explosive sexual power.It was people like Alma, Lehrer quipped, who make you realise how little you’ve accomplished. She was both ‘the loveliest girl in Vienna’ and ‘the smartest’.

Alma has been portrayed in a host of books, plays and films. She has even given her name to a problem. ‘The Alma Problem’, coined by musicologists and Mahler scholars, refers to the ways in which she falsified and manipulated the written record of her life with the composer to her own advantage in the decades following his death in 1911. Her destruction of all but one of her letters to Mahler makes it almost impossible to determine the extent to which she acted as a nurturer of, and muse to, his genius.

She is problematic, too, as a biographical subject not least because her behaviour is such a mass of contradictions. She never lost the taint of anti-Semitism prevalent from her youth in the last years of the Austro-Hungarian empire and spent a lifetime making startlingly offensive remarks about Jews, fuelled in old age by her daily bottle of Benedictine liqueur. Yet she married two Jews — Mahler (a convert to Catholicism) and Werfel — and bravely stood by Werfel when his books were burned by the Nazis, following him into exile in America, all the while making it clear that she supported neither the ‘bacillus’ of Nazism, nor its ideological anti-Semitism.

The Alma of Passionate Spirit is a more sympathetic creature than the monster of previous biographies. She may still act abominably, but Cate Haste has wisely forsaken the harshly judgmental tone so often used about Alma, and corrected significant errors that have contributed to the monster legend (for example, the despicable Elias Canetti described witnessing Alma’s false tears, ‘like enormous pearls’, at her daughter Manon Gropius’s funeral, even though Alma turns out not have been present at the ceremony).

Haste makes it clear that Alma’s overwhelming desire to ‘fill her garden with geniuses’ stemmed from her idolisation of her father, the court painter Emil Schindler, who died in 1892 when she was 13. Alma had begun to compose on a pianino when she was nine. By 19 she knew Wagner’s operas by heart and had determined to ‘be a somebody’. But at the same time she recognised her own vulgarity and superficiality, and her longing to bask in someone else’s reflected glory.

When Mahler, 20 years her senior, proposed to Alma in 1901 her doubts centred on the dilemma of whether she loved the man himself or ‘the wonderful conductor’ (she was lukewarm about his music). She also measured him against her current passion, the composer Alexander Zemlinsky, asking herself in her diary: ‘What if Alex were to become famous?’ This ability to grade husbands and lovers according to a fame and creativity rating established a pattern for the future. When her marriage to Gropius failed, Alma wondered how she could ever be expected to be interested in ‘art of a moderate talent’.

Mahler’s devastating letter to Alma, weeks before their marriage, in which he told her to give up her own ambitions as a composer and accept her position as a ‘loving partner’ supporting his work, has rightly been attacked as a monstrous ban on a woman’s artistic expression. Seventeen songs by Alma survive in published form and they have won modern plaudits for their gift of melody. Haste writes of music as being at the core of Alma’s being; and yet she never returned to composing, even after Mahler’s death. For such a forceful, independent personality this is surprising, and it’s all too easy to subscribe, as Haste does in part, to a myth of Alma’s own making, that although Mahler ‘meant me no murder’ he had effectively murdered her genius.

So instead she fed the creativity of others. Werfel couldn’t decide whether Alma was his ‘greatest joy’ or his ‘greatest disaster’, but there’s no doubt that she forced him into becoming a more successful writer. Her power over men lay in their belief that she would make the best of them. She was vain and at times cruel. She was also magnetic, beautiful and sexy.

Kokoschka thought that he couldn’t live without her. After their affair ended, he commissioned a doll-maker to create a life-size replica of Alma. The finished doll was as beautiful as Alma, even though its breasts and hips were stuffed with sawdust. Dressed in the finest Paris fashions, it accompanied Kokoschka on rides in his carriage — though he denied claims he took it to the opera. Eventually, doused in red wine, the Alma substitute lost its head at a party — an image, Kokoschka said, of the spent love ‘that no Pygmalion could bring to life’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in