I couldn’t help thinking, as I read this book, of an old story, vaguely recalled from English A-level classes, about the poet and verse dramatist Gordon Bottomley. I can’t remember now which of his plays it concerns, but it must have been just after the notorious MP and swindler Horatio Bottomley had been imprisoned for fraud in 1922, because as the curtain fell on the final excruciating scene there was a shout from the audience: ‘My God, they’ve gaoled the wrong Bottomley!’

A reader is not going to get very far with Daisy Dunn’s new biography — the opening four lines, in fact — without a sinking sensation that the author has landed herself with the wrong Pliny. It feels very much as though this book was originally conceived as a dual biography; and even in its finished form, the figure of Pliny the Elder — soldier, administrator, admiral, naturalist, inexhaustible encyclopaedist and most famous victim of Vesuvius — looms large enough in the background to make his decent, rather timid and mildly self-congratulatory lawyer of a nephew seem pretty dull fare.

If it perhaps says it all that while the ‘Elder’ sailed into the eruption for a closer look the 17-year-old nephew stayed at home to read, it does mean that it was the Younger Pliny who got to tell the tale. Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus — to give him his full name — was born in Comum around AD 62 and, after studying under the influential rhetorician Quintilian, divided his adult life between the Roman courts and his country estates, working his way steadily but unspectacularly up the senatorial ladder during the dangerous reign of Domitian, before ending his days under the great Trajan with the governorship of Bithynia-Pontus on the Black Sea.

We know what we do about him — and that is a lot — through the large number of letters of his that have survived to become an important source for historians of the Roman world in the second half of the 1st century AD. In some ways, the most significant letters he left are those to and from the Emperor Trajan; but Pliny himself would have wanted to be known — and the Younger Pliny desperately wanted to be known and remembered — for the wide-ranging correspondence with his friends that form the solid basis of this life.

If Pliny clearly wrote with one eye on posterity, however, that is possibly because he suspected that he was not quite the man his uncle was, and Dunn is not going to

disagree with that. ‘His was a logical rather than a creative mind,’ she writes of him,

attuned to detail and hard fact, obedient to protocol. Where his uncle was creative, Pliny was pedantic. You can tell from his prose how much care he took in finding the right phrase to express himself. Whereas Pliny the Elder was economical with his words but prone to write in sentences which changed direction with his every thought, Pliny favoured a more methodical and measured style, which reflected his occupation and approach to life more generally.

That all seems pretty fair — and the book is full of sharp, well-made judgments — but if this biography cries out for one thing it is for a bit of good old-fashioned pedantry. In her preface Dunn writes that she has followed ‘the spirit of both Plinys’ in eschewing a strict chronology; but it might be truer to say that what she has eschewed is the measured and carefully edited tone of the Younger for the scatter-gun digressions, abrupt shifts and free-range curiosity of the uncle.

Pliny the Elder claimed of his 37-volume Natural History — an ‘immense register of the discoveries, the arts and the errors of mankind’, as Gibbon called it — that it contained more than 20,000 facts, and In the Shadow of Vesuvius can’t be far behind. It was clearly tempting to run with every hare that the old curmudgeon put up; but however much fun there is to be had out of his Natural History, what this book badly needed was a firmer and duller narrative structure that placed the character and letters of the Younger Pliny in their historical framework.

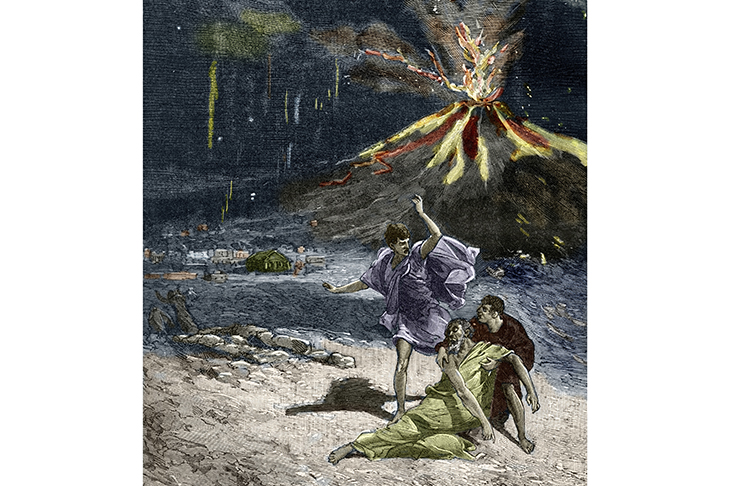

Dunn is a trained classicist, knows her subject inside out and is equally at home with the letters or the Renaissance cult of the Plinys — but that is in a sense the problem. It is possible that Pliny specialists could successfully navigate these waters, but for general readers who, at any point in the book, are likely to find themselves swept up on a tide of associative ideas that might range in just a handful of pages from a Pliny dinner party and the prophylactic powers of lettuce to Cowper, Montaigne, Hadrian’s Wall, Hadrian’s wife, Suetonius, giant oysters and Sigmund Freud, there is a real danger of feeling not just at sea but heading towards Pompeii on a particularly bad day in AD 79.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in