In 1965 a journalist asked Paula Rego why she painted. ‘To give a face to fear,’ she replied (those were the days of the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal). But when asked the same question shortly afterwards, Rego added a qualification: ‘There’s more to it than that: I paint because I can’t stop painting.’

Rego has carried on making pictures ever since and the results can be seen in a remarkable exhibition, Obedience and Defiance, curated by Catherine Lampert at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes. This is not quite a career retrospective — Rego will get one of those at Tate Britain in 2021. But it is the first time that I have seen so much of her life’s work laid out consecutively in one place.

The effect is truly powerful. Sometimes when an important artist passes the age of 80 — Rego was born in 1935 — it becomes clear that what they have done is going to last: they are joining the old masters. You can see that happening to Rego now.

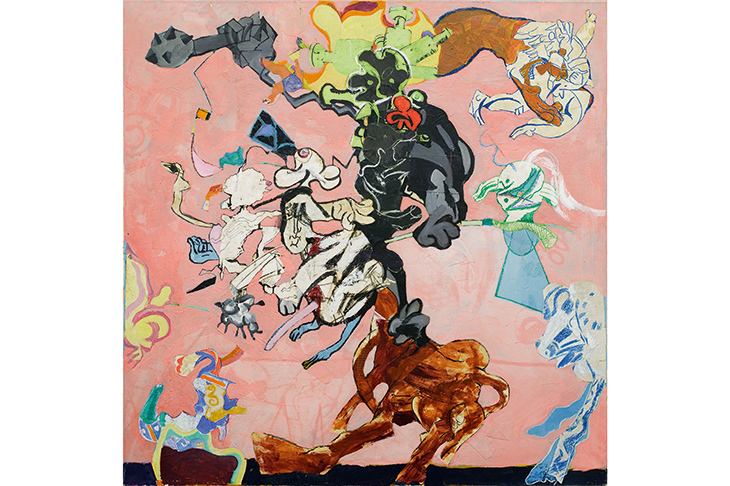

Her work is full of echoes of the past — Goya, Ensor, Zurbaran — but at the same time it is completely contemporary. These pictures might have been made by one of the women from Goya’s work, but reincarnated in modern Britain, rueful and angry about the way her gender had been treated.

The pictures are also full of Rego’s own experiences, imagination and emotions. She remembers how country girls used to come to the door of her family house, begging for money for a clandestine abortion. These memories underlie a number of vehement works from the late 1990s.

Rego does not feel, she once told me, either Portuguese or British, but ‘exactly both’. She was born and brought up in Portugal, educated at the Slade in the early 1950s, then returned to her native land for much of the time until the 1970s, since when she has been working in London.

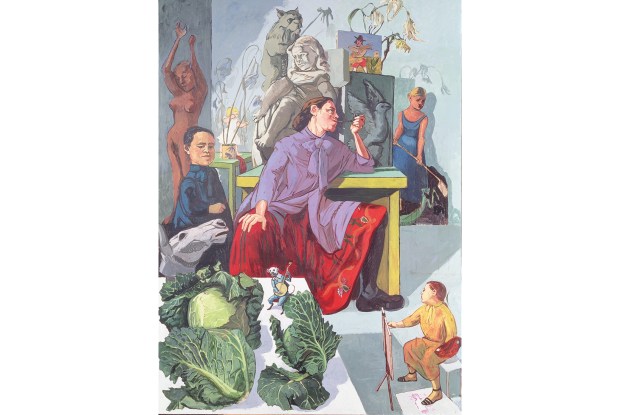

Her early work was angry, visceral and almost abstract. But since the mid-1980s, she has worked mainly from life — or at least from real sights in front of her eyes. Some of her models are specially constructed dummies or dolls resembling the carnival masks to be seen in Ensor and Goya.

The giant stuffed figure in the ‘Pillowman’ series from 2004 is a memorable example. Huge, blubbery and helpless, he dominates the pictures, surrounded by girls and women who both support him and are cradled on him. The Pillowman is typical, too, of the layers of meaning in one of Rego’s images. He was inspired by a play of the same name by Martin McDonagh. But as she worked on the pictures, Rego realised that the Pillowman also stood for her father.

There may be a real object or human being there in front of her, but Rego blends autobiography with narrative and fantasy. Thus ‘Angel’ (1998) is simultaneously a model in the studio and a figure taking part in a classic 19th-century Portuguese novel, The Crime of Father Amaro by Eca de Queiros. Rego invented this Angel, who doesn’t appear in the original book, to avenge the wrongs done to the girlfriend of the central character, a priest.

She wears a costume like a figure in a 17th-century painting — in fact, Rego’s inspiration was Murillo — carries a sword and a sponge, and fixes us with a piercing look. You guess she stands for Rego herself. The artist has spoken of how her assistant, Lila Nunes, who has posed for numerous pictures, constantly looks different because Rego identifies with these images herself.

The references and stories would not count for much, though, if the pictures did not have such authority. It doesn’t matter if you register all the undercurrents of Angel; she is just tremendously present. And that is essentially a visual matter. It’s partly the result, perhaps, of working from life, and also of the vibrating strokes of colour that make up the picture.

In the mid-1990s Rego began to work in pastel, which turned out to be her ideal medium. It gives a shimmer and vitality to her pictures that the earlier ones, in acrylic, didn’t have. Pastel is a way of reconciling painting and drawing, which is why it appealed to a great draughtsman such as Degas. With Rego it’s the same. Picasso was famously dubbed a ‘painter-sculptor’; she is a painter-draughtsman. What she said all those years ago was not quite accurate. It’s drawing she just cannot stop doing.

Rego was obviously enormously talented from the beginning — L.S. Lowry offered to buy one of her student works, saying: ‘I couldn’t do that.’ But she has blossomed since she turned 60. As you walk through the rooms at the excellent new MK Gallery, the experience just gets stronger and stronger. This exhibition is a definite coup.

Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, until 22 September

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in