The defining feature of Chinese millennials is not Instagram, avocado on toast or propertylessness. Born in the early years of China’s growth miracle, my generation idled away days on dusty village roads that would be paved as we grew up. Our adolescence coincided with the arrival of the smartphone; and now, with our jet-setting cosmopolitan ways, we drive China’s global tourism boom. We are as much at home with squatting toilets as with Starbucks menus.

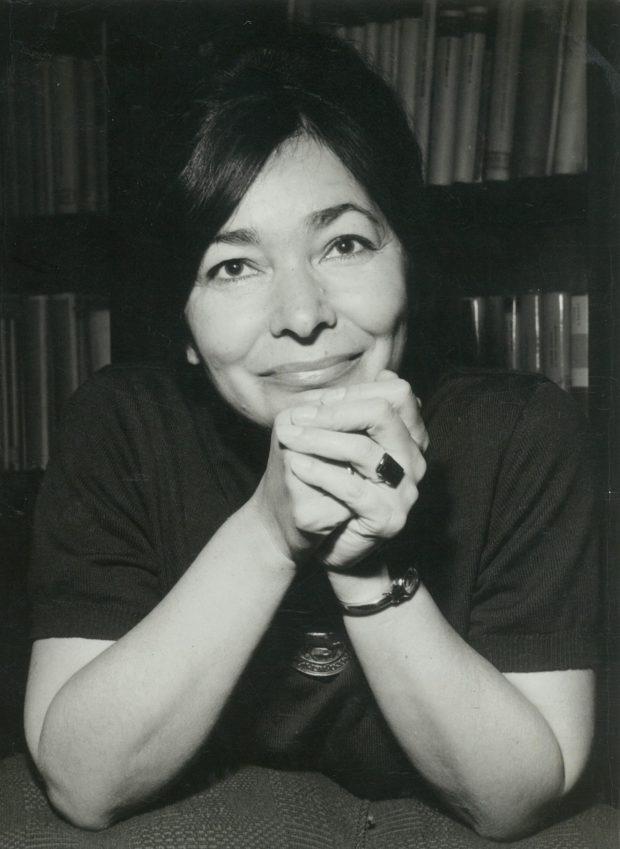

In Under Red Skies, Karoline Kan tells her own millennial story of rags to riches. She was born into a poor farming community, where her grandfather tilled the fields. When she was in primary school, the family moved to a nearby town, uprooted by the sheer determination of Kan’s mother, Shumin. They were ostracised as newcomers: migrants who would always be one rung below the townies. But Shumin’s gamble paid off when her daughter was accepted by a Beijing university. From there, Kan refined her self-taught English and launched herself into a career in English-language journalism — progressing from farm fields to glitzy evenings in the capital, complete with tiger mum, propagandistic teachers and an eventual culture clash with her roots, all within three decades.

Her memoir allows us a peek into ordinary Chinese lives through the eyes of one of those adaptable millennials. As a journalist, Kan is, unsurprisingly, critical of those in power in Beijing. She’s seen the footage of Tank Man, rolled her eyes at the compulsory military camp that comes with university education and knows how to use VPNs to scale the Great Firewall.

Much has already been written about China’s indoctrination of its children, its one- child policy and its persecution of religion, and there’s little new in Kan’s take on politics. But her illumination of Chinese social values is more valuable. How exactly do the lives of ordinary Chinese differ from those of Brits or Americans, and how differently do they see the world? These norms and rules are centuries in the making, surviving tenaciously in the cracks of the communist clean slate. Kan is a feminist and takes after her mother, who was mad enough to plan a second pregnancy in the 1980s, when the one-child policy was in full swing. She becomes indignant when she learns that her grandmother had forbidden her mother to go to university — because education was for boys — and is critical when her teenage cousin is pressurised by the family into a shotgun wedding. Upon finding herself viewed as a ‘leftover woman’, she joins a play called the Leftover Monologues, much to her family’s horror.

Stories such as these may seem less sensational than those about social credit or internet censorship, but they form a larger part of real millennial concerns, especially for young women. On the Chinese preference for sons, Kan writes:

People — like the villagers in Chaoyang — could cite dozens of reasons why boys were better… Boys sweep your tomb after you’ve passed away. (Yes, this last one was relayed to me as a valid reason — as if girls cannot sweep!)

Wherever she is — whether rural idyll or urban tower block — Kan works hard to take you with her, and it’s all quite charming and nostalgic:

The backyard was our secret garden. From here we could see the farmers under their straw hats; mothers stringing red peppers and corncobs, hanging them out to dry; grandparents chaperoning grandchildren home after school; and the neighbourhood yellow dog chasing cats and chickens up the road.

Under Red Skies is no literary classic, though. Too often it flits between childish storytelling and undergraduate formalese, reading more like Gossip Girl than Wild Swans. Still, it will help any reader understand the China beyond the headlines.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in