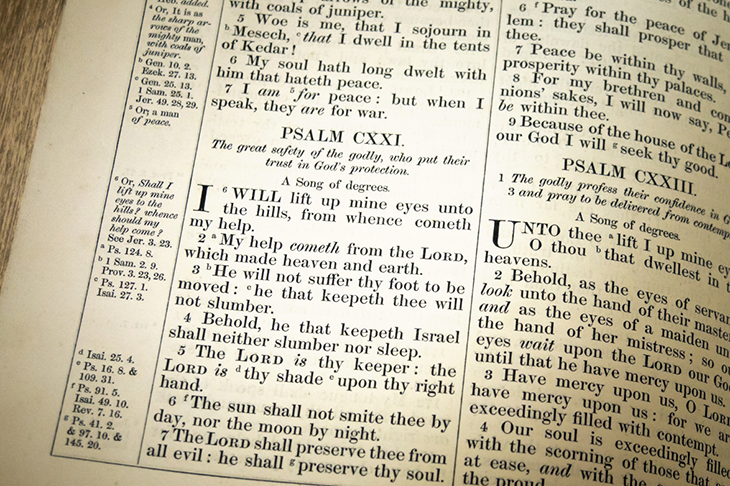

Considerate to the last, she had her order of service arranged in her mind. I sat close with my notebook. She didn’t want a eulogy, she said, but she is definite about the hymns and readings. To kick off, she would like that old Russian roof-raiser ‘How Great Thou Art’. Then, ‘Lord, For the Years Your Love Has Kept and Guided’. And for the big finish: ‘In Christ Alone (My Hope Is Found)’. If there is to be a psalm, she would like number 121: ‘I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.’

Lately there’s been a funeral a week in the village church. Currently on the mantelpiece are three funeral order of service booklets commemorating deceased neighbours. I heard Michael Heseltine say on the radio the other day that by his reckoning a mere 100,000 ‘old white people’ stand between him and his dream (or fantasy) of human progress for this country. I would say to him, please don’t worry, my Lord. Around here, even in their decrepitude, those who were children during the last war — bombed, bereaved, evacuated — are obediently doing their bit for your latest version of the greater good by dying like flies. From the front of these order of service booklets, their former, much younger selves smile out, startling to those who knew them only in old age.

And does she have a photograph in mind, I asked her? No, she said. Whichever. I went to the cupboard where her old photo albums are stored, pulled down a stack and started leafing through it. I’ve never been sentimental about my own or my family’s past. I don’t even remember much of it. Also I am indifferent to photographs because I don’t believe in them. Those who take photographs to be an accurate representation of reality must be mad. On a four-and-a-half-month truck journey across Africa in the late 1980s I took a cheap camera and a single 24-exposure roll of film and I didn’t reach the end of it. The best-composed of the developed pictures were those taken by whoever stole the camera in Bangui, then very sensibly threw it away in disgust, and a close-up taken by our Australian driver of a distended boil on my anus. So I’ve never been one to get out the family albums from time to time for an orgy of reminiscence.

In the first album, there we all were, the family as our younger selves, unperplexed as migratory birds, dressed in ridiculous clothes staring defiantly at the camera. Dostoevsky’s father made him stand to attention while he taught him Latin. There was my father, spare as a whippet; he would have done the same if he’d known any. And there’s my mother’s father, unmoved, with a claw hammer in his hand, shrapnel in his leg and a thin roll-up between his lips. The only time I saw him smile was when, as a child, I slammed the car door shut on his fingers as we were saying goodbye. And there is my mother in 1940, a face full of integrity at ten years of age, when they lived next to the aerodrome at North Weald. Her older sister married two pilots in a year, both of whom were killed. And there she is again at 17, pretty as a starlet — prettier — and there she is again in a nursing uniform, third from the left, second row, among 70 other ecstatic nurses who had that day completed their training.

And yesterday, in Sainsbury’s, I couldn’t decide whether to buy her preferred breakfast of Shredded Wheat in the 12 or 24 pack. The abdominal pain and the rest of it has started. Every morning I throw back the curtains on the green field opposite the house and the young cows and their newborn calves and the wide sea beyond, placid as a pond, and the sunshine of yet another glorious May morning. Yesterday she exclaimed with all of her heart: ‘Isn’t God great?’

And every evening lately — it’s been amazing — she faces west in her reclining chair and watches the first of this year’s crop of young swallows stream out of the garage to cavort in the mellowing light of another miraculous sunset. If I remember, I go and sit with her and together we watch the aerobatic show wordlessly until the light fails and she falls asleep again, listing heavily to one side, sometimes with a peaceful expression on her face, sometimes not.

I’ll place those three photographs — child, teenager, nurse — in front of my brother and sister and together we’ll choose one for the front page of her funeral order of service. Hearty congratulations, my Lord. Yet another old white person standing between you and your idea of progress is about to kick the bucket.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in