In Stockhausen’s Klavierstück XI hands become fists, arms and elbows clubs, shoving, pounding and ker-pow-ing the keyboard to near oblivion. No wonder Pierre-Laurent Aimard had slipped on a pair of gloves before starting to stop his fingers from bruising or bleeding. The sound created is monstrous, alarming, thrilling. Aimard threw the full weight of his body behind each blow to such an extent that I could see his backside hovering above his stool. It’s not easy to beat up a Yamaha grand.

We always dismiss Stockhausen when he claimed that he came from the star Sirius. But his work backs him up. His Klavierstücke are exactly what you might expect from a dazed alien. The series is like a musical version of the Book of Genesis, each piece rebooting one fundamental element of composition. Let there be pitches scattered like stars, pronounces the first. Let there be registers and space, says the second. Chords! (No.3). Sexy chords! (No.4). Rhythm! (No.5). Five almost sounds like music. The first few are subatomic. From 5 on, things become multicellular; there are even hints of mangled narratives. By 11 things have built up to such complicated heights that the only way out is a cataclysmic Fall. Aimard dispatched this hour and a half of music with unbelievable energy.

Stockhausen was always at his best when not attempting to be an Earthling. But he was sometimes a victim of his own otherworldliness. Kontakte’s fusion of percussion, piano and electronics splashes and splats, bubbles and zings, zaps and zwangs. It must have boggled the ear in 1960. Now, alas, it sounds like Star Trek.

Mantra sees two pianists become eggy, crotales-dinging yogi, furiously competing over how to dissolve their pianos in an electronic soup. It works mainly because Stockhausen decides to harness the most futuristic technology of 1970 to make the two grands sound like jangly pub pianos.

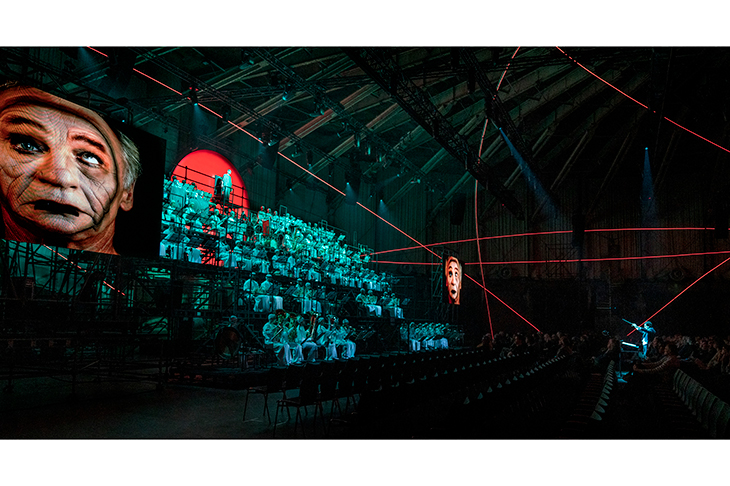

From Mantra on, his alien side becomes ever more prominent, culminating in his insane seven-day opera Licht. This spring there was an unprecedented opportunity to get to know this notorious work. In London you could catch Donnerstag for the first time since 1985. Paris was staging Samstag. And at Amsterdam’s Holland Festival, in the epic industrial drum that is the Westergasfabriek streaked with multicoloured neon, 1,000 people bathed in a spectacular three-day selection of highlights from all seven operas. The stats alone made the eyes water: 450 rehearsals, 412 costumes, 200 wind and brass players, 158 singers. It sounds more daunting than it was. There are passages that strike you with such force — like the orchestra shaped into a giant face that winks, jeers and snarls at us — that you won’t care why, for example, the pianist is dressed as a budgerigar.

Autobiographical Donnerstag opens ravishingly, floating in an amniotic fluid of ambient electronic gurgling. Le Balcon at the Royal Festival Hall presented it with admirable clarity, with some flash Mondrian-y touches in the lighting, but their dancer tai-chi-ed around the stage in a cloth cap looking like a lesbian Oliver Twist.

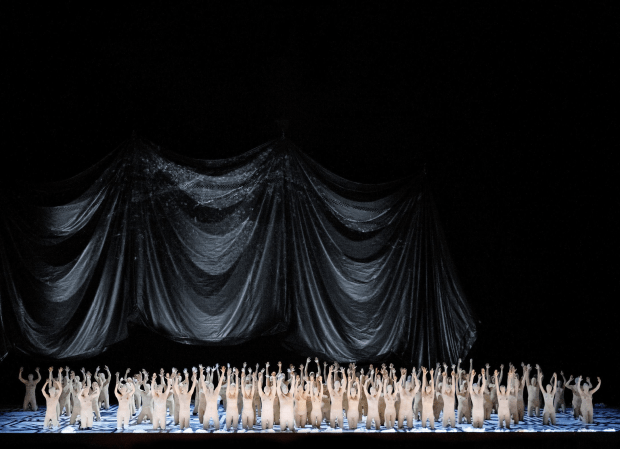

Aus Licht’s choral sections were terrific. ‘Angel Processions’ from Sonntag sees seven choirs massed in the gloom, dressed in swooshy white gowns, circling us while speaking in tongues and firing out extraordinary kissing sounds that exploded like electric sparks. For all the surrealism, however, the operas don’t completely break with tradition. The central story is as old as the hills — a love story between Michael and Eve and their battles with Lucifer. War erupts. Battalions of trombonists fight trumpeters, their sonic sorties whizzing across our heads. And guess who had the best tunes? Yup, whenever Lucifer wielded control, such as in ‘Kathinka’s Chant’, you were in for a treat. Here, a flautist dressed as a cat (the astonishing Marta Gomez Alonso) manipulates and directs six silvery percussionists who wear their metal instruments like armour.

It trumped the infamous choppers from Mittwoch, who scooped up a string quartet and zipped around the skies above Amsterdam as the string players duetted with the sounds of their helicopter captors. I still tend to agree with what Boulez once told me: that the only way it could be interesting is if the choppers crashed. There were lower lows. Boulez said Stockhausen was inventive but not self-critical. The ‘foutouristic’ solo of Mr Synthi-Fou, ‘a mad synthesizer player’, was inventive in the same way that the character Mr Blobby was, I guess, technically inventive.

What ultimately undermines Licht are not the surrealist flights. These have a dream logic that you can get behind if not fully understand. What kills it is its suffocating masterplan. Being a megalomaniac systematiser (and German), Stockhausen has a headmasterly side. So all the operas at some point descend into a kind of Latin lesson from hell, with Herr Stockhausen amo-amas-amat-ing us to death with musical permutations derived from the all-powerful ‘superformula’.

You leave awe-struck but also, as a mere Earthling, a bit frazzled.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in