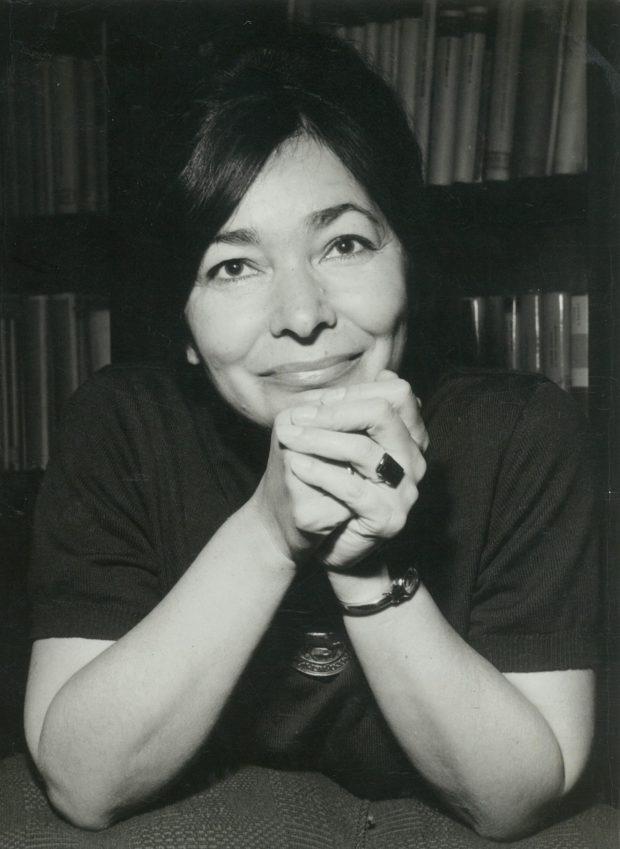

Serious readers and serious writers have a contract with each other,’ Deborah Levy once wrote. ‘We live through the same historical events, and the same Pepsi ads. Writers and readers, nervously sharing this all too fluid world, circle each other to find out what the hell is going on.’

Figuring out what the hell is going on within the fluid worlds of Levy’s fiction is not always straightforward. While other authors are increasingly drawn to autofiction, for Levy, uncertain times, it seems, call for uncertain realities. The characters in The Man Who Saw Everything shape-shift, and time bends back and then twists upon itself again. Objects and animals — wolves and jaguars; sunflowers and cherry trees; a string of pearls and a toy train — echo throughout like leitmotifs. It may be best not to try to pry apart the seams and just enjoy looping the loop along Levy’s carefully crafted Möbius strip.

Longlisted for the Booker Prize, The Man Who Saw Everything joins Levy’s two most recent novels, which made the Booker short list: Swimming Home (2011) and Hot Milk (2016). It opens in 1988, with 28-year-old historian Saul Adler struck by a Jaguar as he tries to cross Abbey Road. The car’s wing mirror splinters, launching us into Saul’s kaleidoscopic vision of events. The driver is dubious about Saul’s age, and a ‘small, flat, rectangular object’, with a voice emanating from within, lies in the road — making us wonder whether we are indeed where (and when) Saul says we are. Walking away from the accident bruised but intact, he visits his girlfriend, Jennifer, who sleeps with him and promptly dumps him.

Saul then travels to East Berlin for research, bringing along the ashes of his recently deceased communist father. Saul has a prescient awareness of the impending fall of the wall, down to the exact date, casting further doubt on his reliability as a narrator. He has a love affair with his translator, Walter, and also beds Walter’s sister, Luna. (‘I think I had less sex in social democracies than I did in authoritarian regimes,’ he reminisces later.) Levy adeptly captures the ambience of life in the GDR, from the ever-present surveillance down to Luna’s pining for fruit and a pair of Wrangler jeans.

The second part of the book is set in London in 2016, in the days following the Brexit vote, with Saul, who still thinks he’s 28, again hit by a Jaguar crossing Abbey Road. This time, the injuries sustained are graver: he comes to in hospital with a ruptured spleen and a ruptured sense of reality. He entertains visits from a 51-year-old Jennifer; his current partner, Jack; his brother and nephews; and his father, who — to Saul’s surprise — is very much alive. ‘How do you write a coherent character,’ Levy wondered in a 2013 interview in The White Review, ‘or why should you?’

Betrayals, real and imagined, are a recurring theme. ‘We are East and West looting each other,’ Levy wrote in her 1989 novel Beautiful Mutants. Saul is aware that Walter is reporting on his comings and goings to the Stasi: ‘I knew his heart was not in it, but he had to save himself.’ Walter further betrays Saul by withholding information about his family situation; Saul betrays Walter with Luna; Luna betrays her son; Rainier, a colleague of Walter’s, likely betrays them all. We learn of Saul’s careless betrayal of Jennifer during a tragic turn of events.

Levy draws clear parallels between Saul and Narcissus: ‘I had gazed at my reflection in the wing mirror of his car and my reflection had fallen into me.’ No self-effacing Echo, Jennifer moved to the States to pursue her artistic ambitions. ‘I was scared of your envy,’ she explains, ‘which was bigger than your love.’ Jennifer’s debut solo exhibition features a triptych of Saul titled ‘A Man in Pieces’: ‘His armpits, nipples, fingers, penis, feet, lips, ears. Floating in space and time.’ Attending the show, Saul realises, with some sadness, that he is only part of a bigger picture.

The oldest known hero’s journey, The Epic of Gilgamesh, begins:

He had seen everything, had experienced all emotions, from exaltation to despair… He had journeyed to the edge of the world and made his way back, exhausted but whole.

Despite displaying a modern, eyeliner-wearing version of masculinity, Saul is stunted by a lack of emotional maturity. ‘I had no idea how to be the man you wanted me to be,’ he tells Jennifer. ‘I have only just started to feel things and I don’t even know what year I am in.’ In order to cross the road that he’s been trying to traverse for 30 years, Saul will not only have to look both ways, but outside of himself. Otherwise, he is destined to remain a man in pieces, lonely in all space-time continua.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in