Nobody warns you when you start medical school that your career decisions have only just begun. Up to a decade of recruitment pitches follow: have you thought about becoming a haematologist? Leave the ward for the drama of theatre! If you don’t like patients, try radiology. A recent flush of popular medical non-fiction lets the public sample this professional pressure. From the heart to the gut, each author claims his or her chosen organ has been unfairly overlooked.

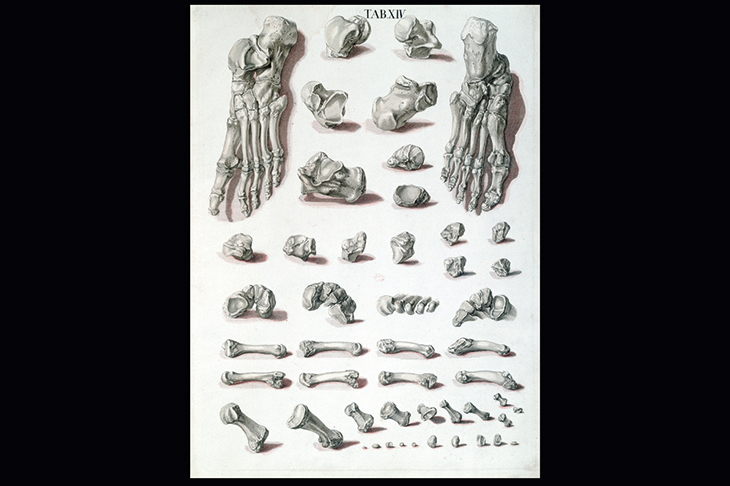

The genre’s most recent additions are about skin and bone. Dermatologists and orthopods are often sidelined as medicine’s aestheticians and carpenters, responsible for the paintwork and scaffolding that encase and buttress the vital organs. The Secret Life of Bones and The Remarkable Life of the Skin set the record straight.

Brian Switek, a science writer and paleontologist, opens his story 530 million years ago with our aquatic ancestor, the pikaia, an extinct eel-like creature, just an inch long, which had the whisperings of a spine. From this cartilaginous precursor, bone developed into something stronger, but still flexible thanks to osteoid rich in collagen, hardened by calcium and phosphate cement.

We lose 64 bones during our lives, or rather they fuse, leaving a set of 206. A dance of creation and destruction between the builder osteoblasts and the demolition squad of osteoclasts continues until death. Despite bone’s resilience in the grave, it’s prone to deteriorate while we’re alive. Weight-bearing exercise protects bone density, but space travel devastates it. Astronauts lose 2 per cent of their skeletal mass per month, or 25 per cent per year, a formidable hurdle to mankind ever reaching Mars. If only we were more like bears, who have no such problem, thanks to a cunning protein activated in hibernation that slows down bone resorption.

Switek turns from evolution and biochemistry to bone’s historical and social complexity. Skeletons tell us secrets about the dead, like the bones preserved under a car park for half a millennium, identified as Richard III’s by his scoliosis, skeletal DNA and chemical isotopes. But collective enthusiasm about the past is not always matched by respect. Human remains were found in Iowa during construction of a highway in 1971. The bodies of 26 Europeans were given dignified burials, while the bones of a Native American woman and child were seized as archaeological specimens belonging to the state. Traffickers continue to find ways to trade human bones on Instagram.

There’s much to learn from Switek’s book, but also a lot missing. The inter-connectedness of our skeleton with the rest of the body is underplayed: alongside the parathyroids and kidneys, bone regulates the body’s calcium levels, responds to sex hormones, provides a niche for cancerous metastases and suffers painful wear and tear which has driven the opioid epidemic. Without these perspectives, Switek falls short as an advocate for bone’s vitality. There’s not even a mention of the critical function concealed within bone’s marrow: haemato- poiesis, the synthesis of blood itself.

These bodily connections are central to Monty Lyman’s book, dedicated to those ‘who suffer in, or for, their skin’. An Oxford-based physician, his descriptions of physiology and pathology never stray far from a patient anecdote. The first rule of examination is to look at the body for any discolouration, lesions, bruises or scars. These often gift you the diagnosis, and are not, as one of Lyman’s surgical colleagues said of the skin, ‘the wrapping paper that covers the presents’.

Skin is a fence and a portal, a vector for communication, a locus of disease and prejudice. The epidermis and dermis are resilient to radiation, pollution, to bacteria and physical insult, while the specialised organs and receptors within the skin are responsible for sweating, sensitivity and pain. The science is thoroughly and imaginatively told, such as when Lyman compares the architecture of female skin to ‘Greek columns’, which allow fat to dimple up through the gaps at the top leading to cellulite, while male skin forms ‘Gothic arches’, capped so that the fat doesn’t show. On the beauty industry, Lyman warns that snake oil is shamelessly labelled as ‘clinically effective’ without regulation. Collagen is an essential component of pliant skin, and a popular cosmetic ingredient, but has no chance of working in a cream because the molecule is too big for the skin to absorb.

We live under our own skin, but others live on it. The dermatological microbiome comprises up to 100 trillion micro-organisms, some partial to the damp creases of the groin or armpit, others favouring drier planes. Our surface is sown at the start of life by maternal vaginal flora or skin bacteria from a C-section incision. Babies born surgically seem to be less well equipped and show higher rates of allergy. But your skin’s microbiome matures and migrates with age. Cohabiting sexual partners can be identified with 90 per cent accuracy from a pool of strangers due to affinities in their skin’s microbial profiles.

I particularly liked Lyman’s ‘psycho-dermatology’ chapter, which explores our skin’s relationship with the brain. The pain and appearance of skin diseases often impacts mental health; stress is known to provoke rashes and aggravate conditions like psoriasis; and the daily fluctuations of affect (such as blushing and sweating) are writ large on our surface. If anyone were to doubt the importance of skin for well-being, Lyman points out that ‘one in five acne sufferers in America and Britain has considered suicide’. From infants’ moles and birthmarks, which were once thought the results of maternal distress or exertion in pregnancy, to the stigmatising dermatological diseases that afflict half of children with Aids, skin remains a focus for exercising judgment and blame. Lyman empathises that ‘for the skin to divide people it doesn’t have to be too dark or too light, but too different’.

What’s true of these books is also true of choosing a medical specialty. The critical ingredient so often is a charismatic, knowledgeable and enthusiastic guide. Bone is a harder sell than skin. But body parts with even less obvious drama or appeal, such as the pancreas or kidney, will probably be the next protagonists asking for your attention.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in